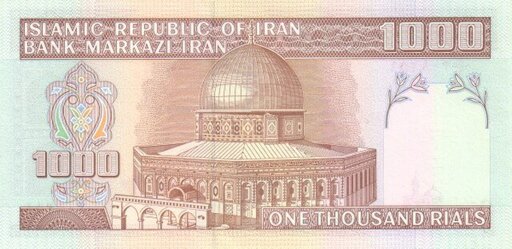

Photograph Source: User:Qian.neewan – Public Domain

In early January, several currency trackers briefly displayed the Iranian rial’s value as “$0.00,” unable to process the speed and scale of the depreciation, making it unexchangeable on important international trading platforms. The fallout quickly translated into a protest in Teheran’s bazaar district and eventually led to a mass unrest.

Unlike the 2019 fuel price protests or 2022 women-led demonstrations, this wave was initiated by Iran’s commercial class and is being seen as a “battle for survival.” Their dissent over the worsening economic conditions drew in other groups around the country, producing widespread instability despite little coordination. Even conservative Iranian government estimates acknowledge more than 3,000 deaths, with other sources placing the toll as high as 30,000. On January 23, 2026, the UN Human Rights Council issued an “urgent investigation” to look into the “brutal crackdown” on protests, which have been “described by UN officials as the deadliest since the 1979 revolution,” according to the Geneva Solutions. The U.S. also announced new sanctions in response to the violent measures and has threatened a military attack, which has led to “worry” in the region. “Hopefully Iran will quickly ‘Come to the Table’ and negotiate a fair and equitable deal—NO NUCLEAR WEAPONS—one that is good for all parties,” President Donald Trump said on the Truth Social platform on January 28. “Time is running out, it is truly of the essence!”

Looming over Iran’s unrest is the question of foreign involvement. Western states and their regional partners have long sought to limit Iran’s influence abroad, and exacerbating its internal turmoil creates an opportunity to apply additional pressure. Yet visible interference, whether through a military strike or admission of operatives on the ground, risks validating Tehran’s claims of outside influence, intensifying repression and provoking wider regional instability.

Economic Breakdown

Iran’s economic foundation, weakened by chronic mismanagement and decades of Western sanctions, suffered particularly severe strain in 2025. Beginning in February, energy shortages disrupted daily life and sharply reduced industrial output, compounded by Israeli targeting of Iranian energy infrastructure during the 12-day war in June 2025. Extreme drought created “water bankruptcy,” raising fears Tehran could run out of water. Additionally, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom activated the “trigger mechanism” under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in Septemberof last year, resulting in the restoration of UN sanctions.

Tehran also faced increasing pressure from Washington. Executive Order 13902, issued in 2020 to weaken Iran’s oil, shipping, and financial networks, expanded through 2025, alongside tougher sanctions on Iran’s “ghost fleet” used to transport oil and evade sanctions.

American authorities have also targeted billions of dollars in Iran’s “shadow banking network” across China, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), disrupting its revenue channels. And though Iran managed to export more oil in 2025 than in prior years, the heavy reliance on intermediaries and steep discounts reduced profits. As access to hard currency narrowed, the rial fell roughly 50 percent over the first 11 months of 2025.

As the government’s ability to stabilize the rial through interest rates, public spending, and monetary policy faltered, black market exchange rates effectively became the benchmark, overtaking official pricing. The crisis mirrors patterns seen in other countries under prolonged financial pressure; the Venezuelan bolivar’s collapse in the 2010s, for example, was a result of bad economic policies and years of U.S. sanctions that began under the Obama administration and intensified under Trump, driving hyperinflation in 2017-2019 and mass protests.

After the bolivar’s redenomination in 2018 and 2021, informal dollarization took hold as the government stopped resisting the dollar’s use. The U.S. dollars became the default for major purchases, while the fast-depreciating bolivar was only used for small, everyday transactions. The bolivar continued to decline in 2025 amid renewed U.S. pressure to remove then-president Nicolás Maduro, leading to further social upheaval in Venezuela.

Similar to Venezuela, the Iranian government has attempted various fixes to prevent a slide, financing deficits by printing money, which caused inflation to surge. As Eurasia Review stated, the government also implemented “a three-tier gasoline pricing system. This caused the price of non-subsidized fuel to jump to 50,000 rials per liter. … It triggered immediate disruptions in supply chains and sent food inflation soaring past 70 percent.”

While currency collapses are commonly imagined as sudden panics, they usually begin as credit failures. Iran’s managed currency system means the government tries to guide its value rather than letting it move freely with market demand. The rial is mostly inside money; accepted for wages, taxes, and domestic transactions inside the country. But it has few users beyond Iran’s borders, where trade and savings depend on outside money, or hard currency, accepted almost everywhere, like the U.S. dollar. As sanctions tightened, Iran’s access to dollars reduced and inflation accelerated, demand for the rial declined because people and businesses began avoiding a currency that was losing purchasing power and was hard to use for imports or savings.

The critical failure came in December 2025. For years, the government sold U.S. dollars at discounted rates to certain importers and some merchants to make imported goods cheaper under sanctions, but dollars had become scarce. At the same time, the official exchange rate set by the government remained largely symbolic and was rarely used in practice. Most people trade at the open-market rate, which was much higher and reflected the real cost of dollars and imported goods.

Subsidies, price controls, and multiple exchange rates helped the Iranian government buy time, but trust in the rial continued to erode as prices, costs, and contracts became increasingly unpredictable. What began as strain in financial markets spilled into daily commerce, leaving merchants unable to set prices.

As dollar scarcity increased, the government began rolling back subsidized access. By December 2025, soaring costs and collapsing profits forced many shopkeepers to close their doors rather than continue operating at a loss, and Tehran’s Grand Bazaar erupted in protest on December 28.

Protests

[Content truncated due to length…]

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed