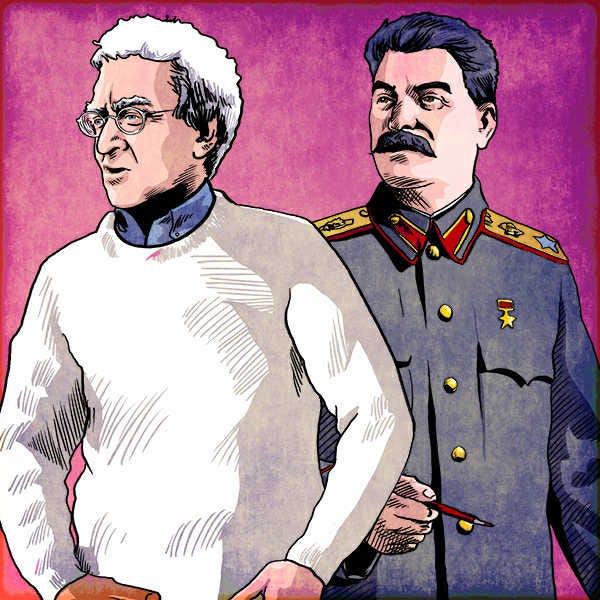

Anyone who reads Philosophy for the People knows that I’m a very big fan of the late Marxist analytic philosopher G.A. Cohen. I’ve written extensively about his arguments against capitalism and for socialism, his defense of historical materialism, his critique of Zionism, and even his position on free will. I’m also co-editing a forthcoming anthology of essays with Matt McManus called Analytical Marxism and Democratic Socialism in the 20th Century: Revisiting G.A. Cohen.

One thing I’ve never written much about, though, is Cohen’s disillusionment with the Soviet Union and what used to be called “actually existing socialism” back when it, y’know, actually existed. (I touched on it in this article, but it wasn’t the primary focus.1) One of his most memorable comments on that subject came in a lecture he gave in Prague in 2001, posthumously republished in an anthology of his essays called Finding Oneself in the Other.There, he recalls:

My Soviet allegiance came from an upbringing in which I was raised as a Marxist (and Stalinist communist) the way other people are raised Roman Catholic or Muslim. My parents and most of my relatives were working-class communists, and several of them had served years in Canadian jails for their convictions. One of those who had been jailed was my Uncle Norman: he was married to my father’s sister Jenny, who, I can tell you, once danced with Joseph Stalin. In August 1964, I spent two weeks in Czechoslovakia, in Prague, on Lermontova in Podbaba, in what was then Norman and Jenny’s home. They were there because Norman was at the time an editor of World Marxist Review, the now defunct Prague-based theoretical journal of the also now defunct international communist movement.

He recounts the same trip in his 1995-6 Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh, which were later reprinted as, *If You’re An Egalitarian, How Come You’re So Rich?*In Edinburgh, his recollections focused on arguments he had in Prague about more abstract philosophical subjects, so let’s start there before moving into the more concrete political realm. I strongly suspect, though, that the former came up in the context of a conversation about the latter.

In the Gifford Lectures, Cohen recalled:

Daytimes I wandered around Prague, speaking with whoever would speak to me. Evenings I spent with Jenny and Norman, and sometimes we argued.

One evening, I raised a question about the relationship between justice, and indeed moral principles more generally, and communist political practice. The question elicited a sardonic response from Uncle Norman. “Don’t talk to me about morality,” he said, with some contempt. “I’m not interested in morals.” The tone and context of his words gave them this force: “Morality is ideological eyewash; it has nothing to do with the struggle between capitalism and socialism.”

In response to Norman’s “Don’t talk to me about morals,” I said: “But, Uncle Norman, you’re a life-long communist. Surely your political activity reflects a strong moral commitment?”

“It’s nothing to do with morals,” he replied, his voice now rising in volume. “I’m fighting for my class!”

We then turned from the problem of the relationship between morals and politics to the problem of identifying Norman’s class.

Cohen’s insistence on not being coy about the moral commitments motivating socialist politics is one of my favorite parts of his “no bullshit” approach to Marxism. Many Marxists, including some otherwise theoretically sophisticated Marxist academics, have been on Uncle Norman’s side of this argument. Some suspect moral philosophy of being an effete waste of time. Others are convinced that making explicitly moral arguments is somehow un-materialist.That second idea is a muddled one, given the logical gap between facts and values. Historical materialism is a claim about the historical facts—about why, for example, we used to have a society of lords and serfs, and now we have a society of capitalists and proletarians, and how and why, in the future, we might be able to transcend that mode of production and have a society of “associated producers” collectively owning and democratically running their own workplaces. It’s impossible for unassisted premises about facts to get us all the way to a conclusion about values.That’s why, for example, conservatives who think they can move straight from “science tells us that a fetus is a living human being from the moment of conception” to a moral condemnation of abortion are confused. Their argument necessarily relies on the unstated but crucial premises that (a) all living human beings (even literally mindless ones like first-trimester fetuses) have a right to life and that (b) this right outweighs the mother’s right to bodily autonomy. All the action happens at (a) and (b). That’s where you get all the interesting moral controversies. And science just can’t answer those questions.

Most leftists will nod along with all of this (even ones who have Uncle Norman-type views on morality). But let’s slow down and notice that moral nihilism (which claims that nothing is morally right or wrong) and moral relativism (which claims that there’s no universal transhistorical standard of morality) are moral conclusions no less than “abortion is always wrong” is a moral conclusion. And moral conclusions can’t be established by purely factual premises like historical materialism.

So goes the abstract philosophical argument against the position that it’s somehow contrary to materialism to care about morality and moral reasoning. What really makes me viscerally impatient with that position, though, is what’s captured in young Cohen’s simple challenge. “Surely your political activity reflects a strong moral commitment?”Because of course it did. No one would be a socialist in the absence of a strong attachment to socialist values.

This isn’t to say that self-interest doesn’t play a powerful (and, in fact, indispensable) role in working-class struggle. Of course it does. For most people, most of the time, solidaristic commitment to doing right by their fellow workers co-exists in an uneasy tension with cost/benefit calculations about what sticking their necks out might bring down on themselves or their families. The difference between success and failure in building a labor union or socialist political party will, at crucial points, come down to whether the movement has succeeded in putting points on the board and thus cultivating the hope that people’s lives will get materially better if they stick with the cause. When everything is going very, very well, there’s a virtuous cycle whereby the work of the hard-core organizers on which any movement necessarily depends manage to build up enough solidaristic culture among the rank-and-file that the workers’ material interests can do the rest of the heavy lifting in getting a critical mass of people on board.

Even for ordinary workers who are in no sense professional revolutionaries, though, solidaristic values are always in the mix. Collective struggle always comes with risks, even if your goals are limited to winning a pay raise and a union. And if your goals go all the way to overthrowing the capitalist system, no one’s going to go broke betting that the forces of reaction will defeat you. This isn’t a fight you get into if you only pick fights you’re confident you’ll win. Even at the rank-and-file level, it’s often a safer bet to keep your head down and pursue individual-level solutions to your problems, or even to make a separate peace with the boss, crossing a picket line or seeking a promotion. Certainly, the hardcore organizers like Uncle Norman wouldn’t stick with the movement through thick and thin, doing things like spending “years in Canadian jails for their convictions” and moving across the world to edit a Marxist theoretical journal in not-exactly-opulent circumstances if they didn’t feel white-hot anger at the many injustices of capitalism and an intense commitment to creating a better world.

Larger normative commitments that go beyond what you personally hope to get out of what you’re doing, in other words, are always going to be a huge motivating factor. So, the question about whether to reason about those values, and see if you can justify what you think, isn’t a matter of “caring about morality” vs. “being indifferent to morality” (as suggested by Uncle Norman’s rhetorical posture). It’s always a question of self-awareness and reflection. Socialist values are going to move you one way or the other. The issue is always whether you’re going to stop and examine those values and think it all through.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that everyone in the world (or even everyone who’s politically active) has an obligation to take an interest in relatively esoteric issues of moral philosophy. There’s a wide range of what “thinking it all through” is likely to look like in any given case, given your general level of interest in theoretical issues of any kind, what particular issues catch your attention, and so on. But, for God’s sake, don’t try to turn the absence of self-awareness and reflection into some sort of weird “materialist” virtue.…especially when you’re face to face with the massive and jarring contradiction between the socialist values you care about (whether or not you’re happy to put it that way) and the ugly reality of the regimes to which you’re aligned.

Marx’s theory of history held that capitalism, with all its brutalities, was a necessary phase of historical development that paved the way for something better. Marx took it for granted that it wouldn’t be possible to build socialism in conditions of material scarcity. Attempts to bring about a democratic and egalitarian sharing of crumbs wouldn’t stay democratic and egalitarian for long.

When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, Lenin and Trotsky were still orthodox enough historical materialists that they took it for granted that a backward semi-feudal country like Russia couldn’t leapfrog to socialism unless the revolution spread to the industrialized West (a possibility already floated by Marx and Engels in their preface to the 1882 Russian translation of The Communist Manifesto).2 At the time, they assumed that it would either spread or be crushed. In some ways, the most consequential tragedy of the twentieth century is that neither of those things happened, so instead we got a grisly verification of Marx’s original prediction, and in the process socialism as an ideal was discredited for generations of people in many countries around the world.3

The isolated and embattled Soviet republic embarked on a brutal forced march to economic modernization that turned the “workers’ state” into something more like a workers’ prison. Millions of peasants were herded at bayonet-point into collective farms that many of them regarded as a “second serfdom.” Stalin implemented an internal passport system, so no one could even move around from town to town without the permission of the authorities, and during the worst of the breakneck industrialization drive, “absenteeism” from the factory was a legally punishable offense. Meanwhile, the regime got so paranoid about internal threats that most of the surviving original membership of the Bolshevik Party was slaughtered in purges during the 1930s. By the time the system was exported to countries like Czechoslovakia following the Soviet Union’s defeat of Hitler in World War II, the original socialist goal of expanding democracy into the economy was a distant memory.It’s true that, by the time Cohen would have been wandering around Prague in 1964, the screws had long since been considerable loosened. The “Khruschchev thaw” had played out and the system never went back to anything like the darkest period of famines and purges it experienced under Stalin. No one in 1964 was being sent to a gulag for “absenteeism.” But these regimes were still economically dysfunctional, hideously bureaucratic, and jumpy about any internal dissent that went beyond painfully proscribed limits. Ordinary citizens still took it for granted that the view of the world they got from the propaganda slop in the newspapers they were allowed to read and the radio stations they were allowed to listen to was distorted beyond recognition. That wouldn’t really change until decades later, when the system was teetering on the brink of collapse.

In the 2001 lecture in Prague, Cohen recalls:

Daytimes I wandered around Prague, speaking with whoever would speak to me. I spoke some Russian and some German, and Norman and Jenny were both very busy so I had lots of time to wander around this glorious city and to talk to people, and, in the evening, to argue with Jenny and Norman about what I thought I had discovered. Going out and about the town, I found no one with a good word for the regime. I returned that first evening and said so to Uncle Norman, perhaps a bit sadistically. I was punishing him for my disappointment: didn’t his total identification with the regime make him a suitable object for that punishment? But Norman had a reply. “Gosh,” he exclaimed, “you must have met some really weird people!” So I went out the next day and, when my polling produced the same results, I presented them, once again, to Uncle Norman. This time his response was graver. “You have to understand that before the revolution there was a considerable middle class in Prague, and they have lost a lot from the workers’ revolution.” And the response to the findings of day three was: “You have to understand, Prague had a huge middle class.” After day three I ceased to seek enlightenment from Uncle Norman: I didn’t want to be told that the middle class had been even bigger than huge.

Part of the reason for the attitudes on the streets was the dysfunction of the system of production and distribution. That’s not the focus of Cohen’s recollections (although he shows a keen awareness of it elsewhere). He remembers thinking “Czechoslovakia was doing tolerably with respect to material provision,” which, in some sense, was true enough. No one was starving. But the system that had grown up in the awful conditions of the USSR’s initial isolation and been exported to Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops didn’t exactly create the kind of “red plenty” that would inspire loyalty to the regime. Seth Ackerman, who explores the problems of Soviet-style planning (and how a more viable socialism would have to work) in his classic Jacobin essay The Red and the Black, is worth quoting at length on this point:

Because the neoliberal Right has habit of measuring a society’s success by the abundance of its consumer goods, the radical left is prone to slip into a posture of denying this sort of thing is politically relevant at all. This is a mistake. The problem with full supermarket shelves is that they’re not enough — not that they’re unwelcome or trivial. The citizens of Communist countries experienced the paucity, shoddiness and uniformity of their goods not merely as inconveniences; they experienced them as violations of their basic rights. As an anthropologist of Communist Hungary writes, “goods of state-socialist production . . . came to be seen as evidence of the failure of a state-socialist-generated modernity, but more importantly, of the regime’s negligent and even ‘inhumane’ treatment of its subjects.”

In fact, the shabbiness of consumer supply was popularly felt as a betrayal of the humanistic mission of socialism itself. A historian of East Germany quotes the petitions that ordinary consumers addressed to the state: “It really is not in the spirit of the human being as the center of socialist society when I have to save up for years for a Trabant and then cannot use my car for more than a year because of a shortage of spare parts!” said one. Another wrote: “When you read in the socialist press ‘maximal satisfaction of the needs of the people and so on’ and … ‘everything for the benefit of the people,’ it makes me feel sick.” In different countries and languages across Eastern Europe, citizens used almost identical expressions to evoke the image of substandard goods being “thrown at” them.

Items that became unavailable in Hungary at various times due to planning failures included “the kitchen tool used to make Hungarian noodles,” “bath plugs that fit tubs in stock; cosmetics shelves; and the metal box necessary for electrical wiring in new apartment buildings.” As a local newspaper editorial complained in the 1960s, these things “don’t seem important until the moment one needs them, and suddenly they are very important!”

And at an aggregate level, the best estimates show the Communist countries steadily falling behind Western Europe: East German per capita income, which had been slightly higher than that of West German regions before World War II, never recovered in relative terms from the postwar occupation years and continually lost ground from 1960 onwards. By the late 1980s it stood at less than 40% of the West German level.

The issues Ackerman describes here go a long way to explaining why workers in none of these countries rose up to defend their “workers’ states” against capitalist counterrevolution at the end of 1980s. A system that had been designed for rapid industrialization was very good at rapidly industrializing and very bad at meeting the everyday needs of citizens, which is why, in Communist states around the world, we get a pattern of initial rapid growth followed by East Germany-style plateaus.It also explains a lot about the persistence of censorship and political repression. The baseline of dissatisfaction with day-to-day economic conditions gave the regimes every reason to worry about the flood of discontent that might be dredged up by allowing citizens freedom of political expression.

As Cohen notes, there were three basic ways that western communists responded to repression of dissent in the Soviet bloc. The “[f]irst, and crudest” was simply denying that there was any such repression. Given the general narrative of disillusionment that frames his reflections, you might expect him to heap scorn on this response. He doesn’t. Instead, he argues that this belief had a rational basis (at least among those comrades who’d never visited countries like Czechoslovakia to see for themselves).

How could we fail to believe what the press reported [about political repression in Eastern Europe], and what the great majority of the people who surrounded us thought?

Well, we thought that that great majority got their opinions from the bourgeois press, so all that needs explanation is why we didn’t believe that press. And the answer is that we knew—I say knew, not believed—that the bourgeois press lied. I do not mean that we knew that it lied about the character of life in the Soviet Union, since, for the most part, it didn’t lie about that, because it didn’t have to. I mean that we knew that it lied about capitalism, that it misreported strikes, for example, that it covered up poverty. The press was owned by capitalists and reported everything from a capitalist point of view. It was motivated to lie about capitalist Quebec and capitalist Canada, and we knew that it did, so why should not for the same reasons lie about the rival, socialist, society? How could we know that it had no need to lie about actually existing socialism in order to paint it in those dark colors?

He’s far more critical, though, of those who made the trip and continued to rationalzie what they saw.4 He writes:

A second and more sophisticated response acknowledged the restrictions, with an expression of regret, followed by a justification of the restrictions that referred to the enemy without and within: there could not, alas, be freedom of speech, because the capitalist world would exploit freedom of speech, for counterrevolutionary purposes. There were different variants of this response. You could make it but also think, for example, that the authorities were going too far. You could think some restrictions of freedom of speech were justified, but that the restrictions actually in force were more extensive than could be justified: you could show how daring, how free you were by saying so. And, finally, there was the most sophisticated response, which was what I believed, namely, that, contrary to the first response, there was extensive restriction on freedom, and, contrary to the second response, (virtually) none of it was justified, but it was something that only or largely affected intellectuals, and one should therefore not get it out of perspective. It was an evil, but a limited evil: one should take care not to conclude that it was a larger evil than it in fact was.

And in August 1964 I learned that that belief of mine was a patronizing view, because lack of freedom of speech cuts everyone off from the truth. If all you’ve got is Rudé právo, and you know it lies, you cannot really know what’s happening in the world around you, and you know your information is controlled by liars, even if you have no wish to express anything yourself. Freedom of speech is imperative not only because no human being has the right to silence another, but also because human beings have not only a right to express themselves but a right of access to the views of others, and to the truth, rights which go beyond the right not to be unjustifiably interfered with (which includes a right to freedom of expression), rights which are more positive, but no less urgent for that. In the absence of freedom of speech, not only are those who would otherwise speak muzzled, but everybody lives in a prison.

These are realities that few people who lived in those societies would deny. They make up a big part of the reason why, in most of those places, any talk of “socialism” has been a complete electoral nonstarter during their three and a half decades of multi-party elections. And given that these facts weren’t exactly a well-kept secret in the rest of the world, they explain a lot of the hesitation about embracing non-capitalist horizons felt by even many extremely left-wing people in countries around the world that never experienced what Cohen was describing first-hand.Nevertheless, he ends the lecture by holding the line on what can and can’t be rationally concluded from the experience of twentieth century Communism:

We thought equality and community were good, we tried to achieve them, and we produced a disaster. Should we conclude that what we thought good, equality and community, are not, in fact, good? That conclusion, though frequently drawn, is crazy. The grapes may indeed be sour, but the fox’s failure to reach them doesn’t show that they are. Should we conclude, instead, that any attempt to produce this particular good must fail? Only if we think we know either that this was the only possible way to try to produce it, or that what made this attempt fail would make any attempt fail, or that, for some other reason, any attempt must fail. I believe that we know none of those things. In my view, the correct conclusions are that we must try differently, in some sense and degree of “differently,” and that we must be much more cautious. It is in that spirit, one of continued but chastened dedication, that the paper “Why Not Socialism?”, to which these remarks are a preamble, was written.

If you know the first thing about my views, you know that I’d enthusiastically endorse that conclusion. Three and a half decades after the Eastern Bloc and similar regimes around the world imploded of their own contradictions need, in Samuel Beckett’s words, to “try again” (and if we “fail again,” at least “fail better” and above all keep trying). The iniquities of class society are far too great to just accept forever that capitalism is the best our species can do.

But it frankly drives me nuts that, in the year 2025, some radical leftists continue to retroactively adopt the political posture of Cohen’s Uncle Norman, and with far less excuse.

In 1964, you could tell yourself that you were contributing to a viable effort to win a global struggle against the capitalist order. (You can’t make an omelette without denying a few hundred million people basic civil liberties.) Now, it’s been so long since the system imploded under the weight of its many contradictions (with most of the formerly Communist countries simply becoming capitalist, and a few retreating to a heavily marketized and wildly inegalitarian hybrid between the two systems) that babies the day the Berlin Wall fell are entering their late 30s. It should be obvious to anyone who thinks about it for 10 or more seconds that the memory of Stalinism (and before that, its ugly reality) has been a major stumbling block to building mass support for radical socialist ideas for generations.

Look. I get it. If you consider yourself to be in an ideological war with the capitalists and imperialists on every other front, it can seem natural to also fight them on the histories of societies like Czechoslovakia and the USSR. Why give your enemies anything? But the reality is that you’re giving them something (in fact something quite valuable) when you try to rehabilitate this history. You’re giving them magnificently potent anti-communist propaganda. “They want to do all that again. Look! They admit it.”

I don’t know how many of these people there are. In the six or seven years I’ve spent doing left media stuff, I feel like I run across them a lot, because they can be a very noisy part of the left media audience, but I suspect (and fervently hope) that they’re greatly overrepresented on social media and in YouTube comments sections. I don’t have any data on that. But, however many or few there are, I really wish they would stop.

Because even the current crop of social democratic politicians, campaigning on modest policy proposals, who gain national popularity while unabashedly using the s-word to describe their politics, would have been totally unthinkable for even most of my lifetime. And I’m not even all that old!

Despite all the setbacks of recent years, I’m optimistic about more radical horizons opening up in the future. As Stalinism vanishes in history’s rearview mirror, many things are becoming possible. But if your instinct at this moment is to say, “Oh, actually, I think that system was pretty great and anyone who disparages it just doesn’t understand that Hard Choices need to be made blah bah blah,” then whatever your intentions, you’re a wrecker.

Thanks for reading Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Do check it out, though, if you’re interested in the details of an earlier phase of his estrangement from the capital-C Communist movement than the one I cover here, or Cohen’s thoughts (decades after the period I’m covering) about the fall of the USSR.

A year before, Marx had received a letter from the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich asking if Russia would have to wait through a capitalist phase before it would be ready for socialism. He agonized over his answer, going through many drafts before arriving at roughly the answer he gave in a much clearer form in the next year in his preface to the Manifesto translation, where he wrote that “[i]f the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other,” it was possible that Russia could skip the capitalist step.

It’s also a historical tragedy that these regimes collapsed rather than being reformed into a more humane and democratic form of socialism—in the USSR in particular, it was really a collapse like something out of a dystopian science fiction movie—but the second tragedy might have been baked into the first.

There’s an analogy here, and probably another essay to be written, about those western Zionists to who or don’t visit “the only democracy in the Middle East” to witness Israeli apartheid for themselves.

From Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis via this RSS feed