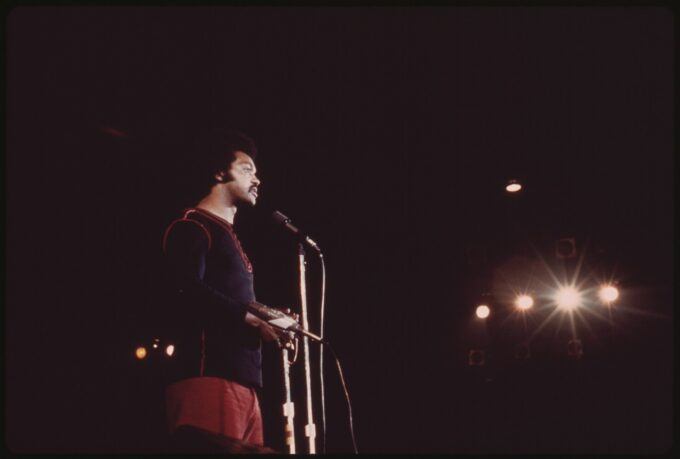

Photograph Source: John H. White – Public Domain

Rev. Jesse Jackson surprised me during a trip to his home state of South Carolina. He asked that I join him in the hospital room of his dying mother, Helen Burns Jackson. I had accompanied him in 2015 to write about his work advocating for then-governor Nikki Haley to accept Medicaid expansion funds from the Obama administration, and for her to remove the Confederate Flag from government property. When his mother became ill, he made his trips to Greenville more frequent, always attaching them to a political purpose. As I was about to learn, Jackson performed a poetic synthesis throughout his 84-years, fusing democracy as political theory, ethical practice, and an everyday lifestyle.

“Baby!” Mrs. Jackson said with excitement upon seeing her beloved son. “Baby’s here, momma” the civil rights leader answered back. He introduced me as a “journalist writing about what I’m trying to do here,” but also as a “friend.” Upon hearing that word, Jackson’s mother reached for my hand, and said, “Thank you for being a friend to my son.” I took her hand.

Then, I stepped into the hallway, allowing a mother and child to have their privacy. When Jackson joined me, he propped himself onto a cast iron radiator, his back leaning against a window under rapid fire of hard rain.

“My mother was a hair stylist by trade,” he said, “But a social worker by faith.” With the storm providing a steady drum beat for the rhythm in his voice, he told me stories about his mother teaching illiterate men to read, helping them fill out forms for employment or government aid. He remembered when she would style hair and apply makeup for women heading to a job interview or big date, even if they couldn’t afford to pay her.

“If I have ever shown desire to help those who most need it, if I’ve been successful in that mission, it is because of my mother,” he said before indicating that we were off to his next mission-oriented task of speaking to Black city council members about how to harness their power to move their state in a more equitable direction.

In his own movement into the Civil Rights Movement and the movement of multiracial democracy, challenging a country that consistently failed to adhere to its foundational fealties, Jackson constructed a hybrid of moral simplicity and political profundity. The cynics and charlatans of America’s sclerotic political system and culture would often miss both elements, accusing him of egomania, personal ambition, and rhetorical divisiveness. It is the common script against dissidents, full of boring lines of slander. Jackson observed the tactic up close when working as an aide to Dr. Martin Luther King, who critics also accused of self-promotion and publicity-hunting. In fact, the terminology and strategy were so remarkably similar that when I appeared on WGN News in Chicago to discuss my book on Jackson, an anchor read absurd quotes I had included from the 1960s about King’s alleged “egotism,” having confused them for ridicule of Jackson.

In reality, Jackson first enlisted into the effort to transform the United States into a society of freedom and justice through no choice of his own. Born in 1941, and growing up Black and poor in the Jim Crow south, he attended segregated schools, heard rumors of local lynchings, and as a college student in 1960, collided headfirst with the terror, oppression, and cruelty of what was then the typical American experience for anyone whose skin was a shade darker than pale.

When attempting to check a book out of the public library, a police officer accosted him, hurled racial slurs, and threw him to the curb. Jackson told me the story decades later – after he had spoken to adoring audiences around the world, after he  had received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, after had acquired power and influence – and yet tears filled his eyes. His emotion was an exhibition of how the wounds of degradation never fully close. It was those wounds that he would try to heal for himself and his constituents, while also practicing the political sorcery of turning pain into inspiration.

had received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, after had acquired power and influence – and yet tears filled his eyes. His emotion was an exhibition of how the wounds of degradation never fully close. It was those wounds that he would try to heal for himself and his constituents, while also practicing the political sorcery of turning pain into inspiration.

Jackson and seven other college students, who the press would christen the “Greenville Eight,” launched the campaign to desegregate the Greenville library system. It was the first of many movements of freedom and equality that he would help to lead.

During one of our conversations, he would tell me that he was actually “frightened” to contemplate what his life would have become without “the movement.” “The movement,” he explained, gave his life “meaning.”

For Jackson, the existential question of meaning was inextricably linked to the pursuit of justice, the enlargement of democratic potential, and politics in the classic, Aristotelian sense of trying to make other people’s lives better. Far from narcissistic self-aggrandizement, his life presents an alternative to the individualism and consumerism at the heart of American culture, which beats like a dull thud under countless social media accounts and celebrity endorsements.

Movement-oriented political life transcends the margin of error in consultancy firm polling and operates according to a calculus combative toward authoritarian power schemes and corporate quarterly reports.

The meaning of his life carried him to Selma, Alabama, where he met Dr. King while they risked their lives for the right to vote. He earned a position on King’s staff, not only fighting against state sponsored racism and the Vietnam War, but fighting for a society of social and economic justice. It carried him to Memphis where he watched a bullet penetrate King’s chest.

At King’s funeral, Jackson spoke into the ear of his friend and hero, whose body rested in a coffin, vowing to preserve his work, message, and legacy, dedicating himself to the advancement of the “dream” of racial equality, the principles of nonviolence, and the end of systemic poverty.

The work began with the staging of a “poor people’s campaign” in Washington, DC, where thousands of impoverished Americans of all races and religions gathered to demand political representation, economic opportunities, and material assistance at the National Mall. The assembly elected Jackson “mayor of Resurrection City.” In his capacity of leadership, Jackson led the audience in what would become his signature affirmation, asking them to repeat the words, “I am somebody.” Those words, in Jackson’s booming and poetic voice, would shatter the psychological restraints of millions of people. From the Black poor in inner cities to Chinese immigrants in California; From students at school across the nation to the elderly veterans of war, those who heard Jackson enunciate the personal creed and political conviction of “I am somebody” felt their backs straighten, their hearts swell, and their feet move to the beat of the protest march and the upward climb.

My mother heard those words. As a dark-skinned white child in the Chicago suburbs, schoolyard bullies would often taunt her, shouting epithets because she was the closest substitute for a Black girl. “I am somebody” reached her as a refrain of belief and purpose. The three-word phrase found its way to the ears of Lori Lighfoot, who would become Chicago’s first Black woman, and first lesbian mayor, crediting her own self-regard to Jackson’s work and message. The affirmation engineered a revolution of the psyche for Norman Fong, an organizer of Chinese immigrants in California, who recalled hating himself after whites tied him to a fence as a young boy. Fong said, “When I heard it,” “I told myself, ‘I am somebody.’ I still tell myself that every day.”

Martín Espada heard “I am somebody.” The Puerto Rican activist and poet told me, “Jesse Jackson’s vision included me, and people like me, and that was a first.”

Even as a white boy coming of age in the suburbs, I intuited that Jackson’s vision promised emancipation. Albert Camus wrote that those living in an oppressive society must aspire to live “neither as victims nor executioners.” When, as a teenager, I first began studying the work of Jackson, I realized that I did not have to live as an executioner. The ambition to live as a truthteller and agent of justice would give my own life dignity.

I met Jackson to conduct my first interview with him 2014. In the years that followed, I talked with him countless times, traveled with him, observed his work up close in Chicago, wrote my book, I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters, and most importantly, developed a friendship that I will always treasure.

Whether it was watching Jackson lead a :die-in,” laying in the middle of the street to protest a police murder of an unarmed Black teenager, speak to a group of students at a Chicago high school, or work closely with his staff during a day at the office, I learned the core principle of Jackson’s theory and practice. Beyond partisan rancor and ideological wrestling, there is a non-negotiable “somebodiness” of humanity that must remain the highest priority in any political agenda. Jackson’s expression and exercise of a steadfast belief in the inalterable “somebodiness” of every person enabled him to imbue his leadership with the power of presence.

His politics, contrary to popular criticism, were not for the television studio or flashbulb press conference, but for the street.

The street is where he joined countless Black and Latinos shut out of an apartheid economy in the 1970s. The organization that Jackson founded, Operation PUSH, challenged the racism and narrow-mindedness of major employers, trade unions, and lending institutions to integrate Blacks and Latinos into American commerce, housing, and entrepreneurship. With his dedicated staff and volunteers, he squared off against the giants of corporate America, ranging from General Motors to Burger King, to secure thousands of jobs for Blacks and Latinos, and millions of dollars in ancillary benefits. PUSH succeeded in civilizing the market, but Jackson understood the limits of the market to create the conditions of justice. “You can inherit a car dealership,” he once told me, “But you can’t inherit a congressional district.”

His mode of activism and organization sought to leverage the consumer power of the boycott and the citizen power of the vote, and he committed to creating a formidable apparatus of Black and progressive political representation that could attack a cruel Republican Party and enliven a comatose Democratic Party.

While registering millions of voters in 1984 on a “Southern Crusade” tour, Jackson responded to an ever-present, ever-loudening chant that acted as an invitation, “Run, Jesse, Run!” His presidential campaigns of 1984 and ’88 demonstrated the power of electoral politics when its engine is the populist energy of a diverse underclass. With the construction of a “rainbow coalition,” he articulated a message of defiant unity: “If we leave the racial battleground to find economic common ground, we can reach for moral higher ground.”

Clawing upward toward the apex of democratic hospitality and harmony, Jackson marched with Latinos, including undocumented immigrants. He slept in hospices alongside gay men dying of AIDS. He spoke to white family farmers who covered their faces with masks for fear of retaliation from the Farmer’s Bureau for supporting a candidate opposed to big agriculture. He visited reservations to meet with Native American tribal leaders. He rallied with Puerto Ricans in New York and the residents of Chinatown in Los Angeles. He told white coal miners in Kentucky and Black millworkers in Detroit that their problems were the same, but so was their political potential if they would only unite in class consciousness.

The positions that Jackson adopted were often called “extreme,” but many have become consensus left of center politics: universal health care, raising the minimum wage to a living wage, paid family leave, tuition free community college, full employment through robust infrastructure and public service programs, the support of Nelson Mandela and anti-apartheid movements in South Africa, and a two state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

With a “poor campaign, rich message,” as he called it, he spoke without electric amplification in church basements in the desolate outposts of the Deep South and high school cafeterias in the inner city. He lost the sprints of the 1980s, but won the marathon of political transformation. Out of his campaigns came the first Black mayors of Denver, Memphis, Seattle, and New York. Out of his campaign came progressive stalwarts, like Bernie Sanders and Paul Wellstone. Out of his campaign came an infrastructure of Black and diverse political talent, like Donna Brazille, Delmarie Cobb, and James Zogby. Without the Black voters that he ushered into the party, Bill Clinton might not have won in 1992. Without his successful campaign to convince the Democratic Party to adopt proportional allocation of delegates in presidential primaries, Barack Obama would not have won in 2008.

During the eulogy for Rosa Parks, Jackson said that when American leaders talk about “democracy promotion” abroad, they don’t mean “Jeffersonian Democracy.” “It has no export value,” Jackson said. “Who wants a white male, aristocratic so-called ‘democracy’ where women can’t vote? They mean Parks-King democracy.” Jackson was a founder and framer of Parks-King democracy.

In a rare moment of complimentary self-assessment, he once told me, “Some people follow a path. I blazed a trail.”

Some of the trails that he blazed never made into media cartography. In 1984, he failed to live up to his own standards when he used a slur against Jews. It was an unfortunate slip that risked fracturing an already fragile Black and Jewish alliance. Jackson apologized, asking that those who were rightfully disappointed, “Charge it to my head and not my heart.” Unlike many politicians who recite a publicist-crafted apology and move on, Jackson spent decades strengthening his ties with Jews, not only in the United States, but around the world. He did extensive work with the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, he advocated for Soviet Jewry, and he regularly collaborated with Chicago synagogues.

Every year, for over four decades, Jackson spent Christmas morning at the Cook County Jail on the south side of Chicago. Speaking and meeting with inmates, he would offer encouragement, oversee voter registration tables for those who had not been convicted of a felony, and inform them of job training and education programs at PUSH. In 2018, I accompanied him and PUSH staff to the jail, where I met Rabbi Samuel N. Gordon from a nearby, suburban temple. He joined the group at Jackson’s request. When I asked why, he said, “I would do anything Reverend Jackson asked.” I assumed wrongly that they were friends for years, but they had met only two months earlier in the days after the antisemitic mass shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Gordon publicized a statewide invitation for any religious leaders to join him for an interfaith denunciation of antisemitism. Jackson was the only Christian minister to attend. He stayed for several hours. There were no television cameras in sight.

The last twenty years of Jackson’s life were rich with stories of unglamorous service, unpopular advocacy for justice, and unparalleled commitment to the principles of democracy. With devoted staff and volunteers, the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, under Jackson’s leadership, fed the homeless, educated the young, welcomed the despised, and remained steadfast to the fight against hatred in Chicago, the United States, and around the world.

In 2015, during the annual dinner for the poor, Jackson displayed how his calling governed his behavior, regardless of his location and audience, whether he was in the company of the Royal Family or a long-forgotten outcast. Wearing a chef’s hat and helping to distribute the mashed potatoes at a Thanksgiving dinner for the poor at the headquarters of Rainbow/PUSH, Jackson greeted each person in line. A man who, despite the frigid temperatures of Chicago’s November, was wearing a t-shirt, nervously ran his hands through his long, purple-dyed hair. He asked for more mashed potatoes, the only food on his plate. It was otherwise empty after he had turned down the turkey, vegetables, stuffing, and cornbread. Jackson said, “I’ll see what I can do,” before explaining that he had to make sure there was enough for everyone else in line. When the influx of diners slowed, Jackson went to the kitchen, asked if there were more mashed potatoes, and after learning that there was a remaining supply, he covered a large plate with nothing but mashed potatoes, walked it over to the purple haired man, and said, “Here you go.”

I’ll never forget visiting Selma, Alabama for the fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday. I traveled with the Rainbow/PUSH delegation by bus from Chicago to Selma. At the end of two days of non-stop activity, while Rev. Jackson marched, spoke, gave interviews, and met with local leadership, PUSH volunteers sat on their bus benches expressing frustration that they were not able to spend more time with Rev. Jackson. His busy schedule simply did not allow for social visits.

Before the bus driver could put the hulking vehicle in drive, we saw a small vehicle with an attached trailer rounding the corner. Like an injured quarterback, Jackson was stretched across the trailer. Wearing a three-piece suit, his ankles were swollen, knees rickety, and his brow soaked in sweat. With all the strength that remained in his body, he climbed aboard the bus and gave a characteristically powerful speech. Then, he took a few steps closer to a volunteer who was wearing a scarf on her head. Her hair was gone from chemotherapy treatments. Rev. Jackson led the volunteers in prayer for her healing, recovery, and happiness.

He made his way back to the trailer. As it pulled out of view, he raised a fist in the air.

The rare, but elementary gift of presence, in accordance with the methodology and philosophy of the Civil Rights Movement, placed him at the front and center of marches for Black victims of hate crimes, the disabled, LGBTQ Americans, and wounded combat veterans – all when these causes were far out of fashion – and it is what led him to tell mourners at the funeral for his friend, Aretha Franklin, “I’ll never stop marching. When I can no longer march, I’ll still be there.”

Had his health allowed it, there is no doubt that he would have stood alongside undocumented immigrants and ICE observers in Minneapolis. Unlike the elected officials who can only offer pat condemnation from the safety of a television studio, Jackson affirmed his political rhetoric with his physical presence. Taking politics from the pathos to the pavement, his solidarity with the disenfranchised demonstrates why Jackson could strive for greatness, and most politicians can only aspire to mediocrity.

Jackson was not a Marxist, and he forever found the means to position himself between the militant left and the establishment, not as a calculating operator, but instead as a mediator of justice. The work began in the late 1960s when he acted as a bridge between the old guard of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers. After the FBI and Chicago Police conspired to murder Fred Hampton, fellow Black Panther Bobby Rush learned that he was next on the list, as the CPD had issued a warrant, under similar circumstances, for his arrest. Rush took refuge at Operation PUSH. Jackson negotiated a public release of Rush into the custody of a Black officer on the Chicago force. When I asked Bobby Rush, who had become a congressman, what he thought of Jackson, he said in the scratchy voice of an elderly man, “Jesse Jackson saved my life.”

I once asked Jackson if he ever considered an independent or third party candidacy. He conceded that in the early 20th Century, at the height of the progressive and populist movements, it would have benefitted the nation if there was a breakaway “Labor Party.” Without such a party, Jackson believed that his role was to keep one foot in the Democratic Party door, and one foot outside, attempting to broker a meeting between activist urgency and political practicality. He was more successful than most historians and journalists realize. The Democratic Party that became multicultural, that elevated women to the forefront, and that actually began to articulate robust positions on the expansion of the social safety net, is largely the party that Jackson envisioned.

“Growing up in the Jim Crow south, every day is a negotiation,” Jackson told me when reflecting on his childhood. His talent for negotiation consistently shamed the State Department. Jackson, enacting only the power of citizen diplomacy, successfully negotiated the release of hostages and political prisoners in Syria, Cuba, Iraq, the former Yugoslavia, Gambia, and Algeria. In the case of Algeria, the government had apprehended a documentary filmmaker from Atlanta, Georgia on a trumped-up charge that violated any principle of free speech. She was staring down the barrel of ten years in prison. After Donald Trump’s first administration refused to intervene, Jackson convinced the Algerians to release the filmmaker with as little as a phone call. It received no press coverage.

The press also largely ignored Jackson’s last successful mediation. After learning that residents of housing project in Chicago were living in squalor with roaches and rats in their kitchens, appliances that did not work, and security guards who sexually harassed young women, Jackson first appealed to Concordia, the corporation that managed the apartment complex. When they reacted with predictable stalling, equivocation, and legalese, he convinced then secretary of housing and urban development, Marcia Fudge, to pledge millions of dollars for repairs and renovations. He also persuaded the Chicago Housing Authority to more closely monitor and regulate the compliance of Concordia with policies of residential safety and sanitation.

The press that was there to magnify every “flaw” (their favorite word, as if Jackson alone possessed them) was conspicuously invisible when Jackson tallied victories for freedom and justice, often saving lives in the process. And they still cannot stop working as dull cartoonists. The obituary in the New York Times zeroes in on his supposed “ego,” quoting the likes of Stanley Crouch and Marion Berry. In its closing passages, it refers to an academic who concludes that “moral leaders” like Jackson are no longer necessary, because we have “elected officials.”

One can flip a coin to determine if that position is more stupid or insidious. As the Republican Party descends into the mania of hatred and violence, far too many Democrats remain passive and complacent, and many Americans swim in the stew of apathy and indifference, moral leadership is precisely what has become essential. Moral leadership of the Jackson style is radical in the classic sense of “getting to the root.” For Jackson, the root of social and political pathology required a transformation of law according to an ethic of defiant solidarity.

My last moment with Jackson was in December. He was staying in a nursing home – bedridden and barely able to speak. One of his aides and I sat in the room, watching CNN, under the impression that Jackson was asleep. We began to discuss the grotesque capitulation of major institutions in the face of Trump’s assault on civil society. I mentioned the Washington Post, CBS News, and corporate America. Before Jackson’s aide could respond, Jackson opened his eyes and said with something of a roar, “Harvard.” He was referring to reports that the Ivy League university would surrender to Trump’s demand of a $500 million payout to the federal government as punishment for various policies that he found objectionable. He was listening. He was angry.

His aide left the room to give us privacy. I thanked Rev. Jackson for his leadership and friendship. I promised him that I would continue to tell his story and promote his message. I told him how proud I am of the years we spent and the work we did together. With that he turned, reaching for my hand. We held hands in silence for ten or fifteen minutes. Then, I said, “goodbye,” knowing the weight of the word. He gestured for me to come closer. I put my ear to his lips. He whispered, “I love you.”

There is a poetic symmetry in the last words that I heard Jackson utter. “Harvard” and “I love you” capture the love and rage that fueled his life, not as separate emotions, but interlocked impulses to right the wrongs of the world, heal the wounds of oppressive trauma, end wars and violence, and create a democracy that could overcome political and economic attempts at domination. He felt rage on behalf of those who, like him, were bullied by men with power. He also loved them.

A version of this also ran on the Washington Monthly.

The post The Poetic Symmetry of Jesse Jackson’s Life: Love, Rage, and Leadership appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed