The scene before me appeared and disappeared and reappeared again with every breath I took, the hot air from my lungs fogging the gas mask that fit snugly over my face. My mother, father, and little sister stood in front of me wearing hazmat suits. It was October 2005, and we’d been among the first in Gentilly, our New Orleans neighborhood, to receive permission to return to our home after Hurricane Katrina. I was nervous. Gentilly had sat beneath up to eight feet of water for weeks. I didn’t know what I would see, or how I would feel.

Our neighborhood had never been this quiet before. There had always been kids riding bikes, or someone playing music from their car or their front porch or their shoulder with a bass line that made the street vibrate. There had always been the sound of a basketball colliding with concrete as boys went in search of a court and a hoop and a game. Squirrels had always scurried through trees, where birds sang. Now there were no birds, no balls, no squirrels, no bikes. Only an eerie silence.

A silver car with clouded windows had crashed into the trunk of the old oak tree in front of our home, its hood bent into a crooked crescent. Branches from that old oak—some as thick as bodies—were scattered across the street and the yard. On the boarded-up window next to our door was a spray-painted orange X, a symbol used by search-and-rescue teams that could be seen throughout New Orleans in the days and weeks after the storm. Each quadrant of the X had a different number. The top quadrant showed the time and date the house had been searched; the left one identified which team had conducted the search; the right indicated any hazards found inside; and the bottom was for the number of people, dead or alive, found there. Our bottom quadrant read “0,” but I am still haunted by the orange spray paint on homes we passed that said something else.

The search-and-rescue team had smashed the glass next to our door in order to open it. It remained ajar. As we entered the house, the smell bombarded us, indifferent to our masks. I had never encountered anything so pungent in my life; it physically knocked me back beyond the doorframe.

[Listen: Floodlines, the story of an unnatural disaster]

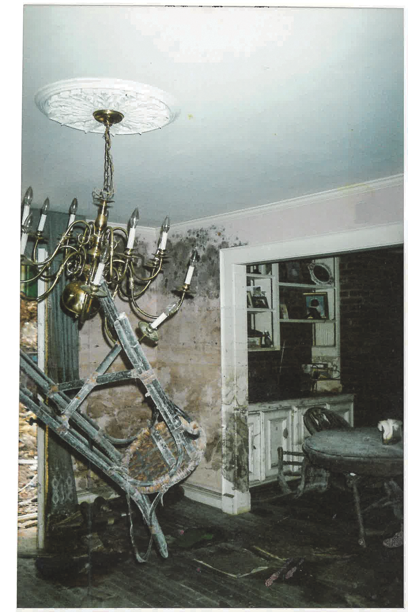

When I stepped inside again, I saw that the walls were covered with mold. Blue-green spores were everywhere. The floorboards were warped; some had come loose. The refrigerator door hung open, rotten food spilling out. The television in the living room was face down on the floor. My mother’s wedding dress, which had been designed and sewed by a local seamstress who had made dresses for generations of Black New Orleans women, lay ruined on the floor beneath the stairwell. A kitchen stool hung by one of its legs from the chandelier in our dining room, but the dining-room table was no longer there. The rising water had lifted it up and carried it into our living room.

As the house flooded, rising water carried the

dining-room table into the living room. (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

As the house flooded, rising water carried the

dining-room table into the living room. (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

We found the mahogany table misshapen, but upright. Sitting on top of it was a glass-domed cake stand with part of a birthday cake still inside, a time capsule unaltered by the destruction around it. Twenty years later, the cake is the thing I remember most clearly.

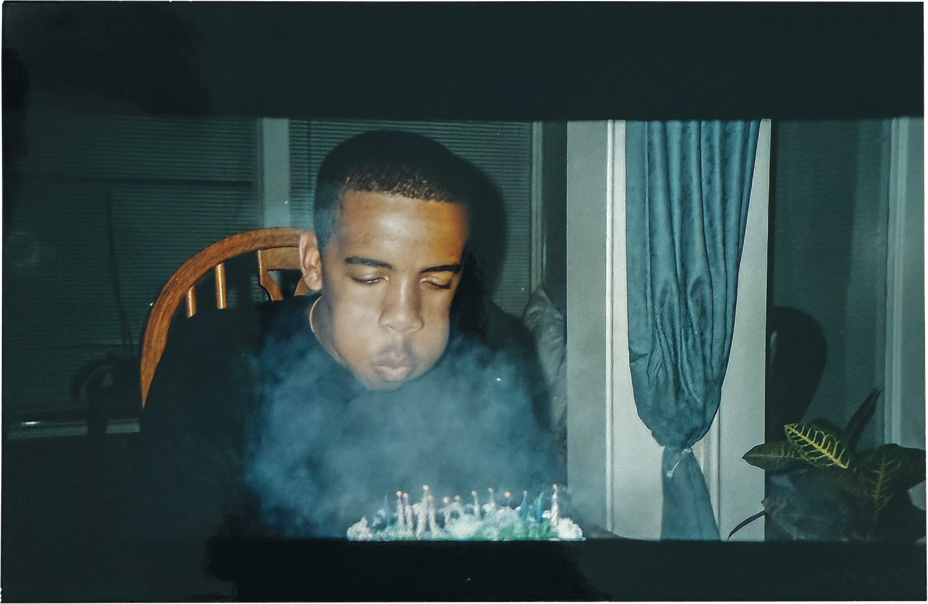

I have never been much of a cake person. I don’t have a sweet tooth, and I hate chocolate. But I made an exception for the vanilla-almond cake with pineapple filling from Adrian’s, the bakery just down the street. I loved the sweetness of the frosting; the soft, slight crumb of the cake; and the candied viscosity of the filling. My parents got it for my birthday every year, and even now, the taste of it makes me feel like a child again.

On August 25, 2005, I celebrated my 17th birthday by eating a substantial slice (or two) of this cake with my family before heading out with my friends to see a movie. When my mother placed the leftover cake inside the dome, we didn’t know that it would stay there for weeks.

Evacuating was not new for us. It was practically a routine: The meteorologists would warn residents about a storm. We would pack some duffel bags with a few days’ worth of clothes, board up our windows, put gas in our car, and drive to Jackson or Baton Rouge or Houston until the storm passed. Then we would come home, pick up a few branches, remove the boards from our windows, and continue on with life as it was before. In 2004, my family had evacuated to Houston ahead of Hurricane Ivan, sitting in 20 hours of traffic for what was typically a five-to-six-hour trip. We’d stayed with my aunt and uncle until the storm passed.

The relative normalcy of hurricanes made many in New Orleans feel as if evacuating wasn’t worth it. Some would decide to stay home and ride out the storm; some didn’t have the ability or means to leave even if they wanted to. We had been told so many times that this storm would be different, only for it not to be. But this time it was.

For Smith (pictured here on his 15th birthday, in 2003), eating vanilla-almond cake from a local bakery was an annual tradition. (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

For Smith (pictured here on his 15th birthday, in 2003), eating vanilla-almond cake from a local bakery was an annual tradition. (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

On August 28, just before 9:30 a.m., Mayor Ray Nagin issued a mandatory evacuation order for every resident of New Orleans, the first in the city’s history. By then, my family and I were already gone. My father recalls waking up at 2 a.m. the morning of August 27 with a feeling of unease. He’d turned on the TV and seen that meteorologists were predicting that Katrina would develop into a Category 5 hurricane—the highest category possible for a storm. And so we packed the bags, secured the windows, and filled the car with gas. My father told me to grab our photo albums off the shelf and put them in thick garbage bags. This, we had not done before. We did the same with pieces of art from our walls, paintings by local Black artists that my parents had collected over the decades. We left the bags in my parents’ second-floor bedroom.

Finally, we got into our car. That night, we arrived at my aunt and uncle’s home outside Houston. For the next several days, I watched nonstop coverage on CNN. I saw people begging for help from rooftops. I saw people wading through shoulder-deep sewer water to reach higher ground, pushing their children in ice chests. I saw footage of floating bodies. I saw homes just a few blocks from mine that were completely submerged. I knew then what had happened to mine.

[Read: The problem with ‘move to higher ground’]

After a few days of sitting on the couch in a catatonic state, I got a call from the soccer coach at Davidson College, in North Carolina. I was being recruited by a few different Division I schools, and Davidson’s coach asked if I’d like to make my official recruiting visit to the school now, as a distraction. I said I would, and my father and I boarded a plane.

At Davidson, I watched the soccer team’s thrilling overtime victory against a local rival, the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I attended a political-science class on the history of the presidency, went to my first college party, and experienced the specific joy of getting late-night wings and quesadillas from the student union. At the end of my visit, I told my dad that I knew where I wanted to go. I committed to Davidson the same day. I realize now, looking back, that I decided on Davidson so quickly because I needed an anchor. I didn’t know where I would be going to high school the next week, but at least I knew where I would be going to college next year.

My sister and I ended up staying in Texas for the entire school year, living with my aunt and uncle after my parents returned to New Orleans in January for their jobs, bringing my younger brother with them. They lived with my grandfather in one of the few areas that had not flooded. That fall, I went to Davidson and my family moved into a new house, one that I was grateful for, but one that never felt quite like mine.

One of the walls in our old family room was covered with mirrors, and as kids, every time my brother, my sister, and I stepped into the room, it felt as if that mirror-lined wall was beckoning us to dance. So dance we did, as numerous home videos attest—bobbing gleefully in our striped hand-me-down Hanna Andersson pajamas to the sound of my dad’s records and CDs. As the trumpets from Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Let’s Groove” blared from the speakers, we would start jumping like the floor was covered in lava, and we would spin like a band of small, graceless tornadoes while my father laughed behind the camcorder.

My father had been collecting records since he was in high school, in the ’70s. He had hundreds—artists such as Chaka Khan, Stevie Wonder, Funkadelic, Grover Washington Jr., Miles Davis, and John Coltrane—stored in the family room’s floor-level cabinets. But amid the haste and chaos of our departure from New Orleans, we hadn’t had time to move them, and when we returned in October, we found the collection destroyed.

The songs we danced to are still available, of course; these days, we can stream them anytime we want. But the albums themselves were artifacts, a tactile manifestation of all those happy memories—and they were irreplaceable.

This year, I went home to New Orleans at the end of June, as I do every summer. I bring my children, because I want them to feel a connection to the city that shaped who I am. Recently, each time I’ve arrived at my parents’ house, I’ve been struck by the fact that they have now lived there for longer than we lived in the home I grew up in. The realization defies my sense of time and language; I’ve referred to this place as “the new house” for the past 20 years.

One rainy afternoon, while my kids were out with their grandparents, I drove down my old street and stopped in front of my childhood home. A new family had eventually moved in, after the house was gutted. There were new windows, new fences, new walls. The red brick facade had been painted white. The old oak tree was still there on the front lawn, its branches extending farther over the street, its trunk having grown darker and thicker with time. The birds had returned, as had the squirrels. People walked their dogs. Two girls threw a softball back and forth.

Although most of the homes in our neighborhood had been torn down and rebuilt, the house across the street from ours looked largely the same as it had when I was a child—except for the two canoes and the kayak conspicuously tied to its roof, as if its inhabitants were preparing for the next disaster.

I then drove to Adrian’s, which had also moved after the storm. There, I was met by the smell of glazed doughnuts and fresh cinnamon rolls. White cakes gleamed from within glass display cases. Sitting on top of the glass were individual slices of cake wrapped in plastic. I walked closer and saw golden pineapple filling seeping out from between layers of sponge. I bought three pieces.

Back at my parents’ house, I opened a cabinet and took out our family photographs.

I’ve always felt thankful that the photo albums and art survived the storm. I tried to imagine what it might be like to no longer have access to these images: the birthdays, the graduations, the baptisms. The beach days, the camping trips, the lazy Sunday afternoons. My father and me flying a kite on a windy day at the lake, his hat turned backwards and his sunglasses glimmering; my mother and me on Easter morning when I was 3 years old, she in a beautiful blue dress and me in a red bow tie and brown brimmed hat; my sixth-birthday party, my face painted like a tiger, looking down at the thick slice of vanilla-almond cake on the table in front of me.

Alongside the albums sat a ziplock bag of other images—photos we took of our home when we returned to examine the damage after the storm. As I spread them out across the dining-room table, I was brought back to that day—the wretched smell, the buckled floorboards, the fungus-laden walls.

I removed the Saran Wrap covering one slice of cake and sank my fork into it, attempting to capture the sponge, the frosting, and the filling in a single bite. It was as good as I remembered it being, and I ate with such abandon that I dropped some frosting onto the photos in front of me. When I moved an album to clean it off, I noticed an image in the Katrina pile that I hadn’t seen before: an old clock that hung above the doorframe in our kitchen, its hands frozen in place. It looked as though it had spores spilling out of it.

An old clock above the kitchen doorframe at Smith’s childhood home (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

An old clock above the kitchen doorframe at Smith’s childhood home (Courtesy of Clint Smith)

When you talk with people in, or from, New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina is often the way by which we demarcate time. When attempting to recall an event, a moment, or an experience, someone will ask “Was it before or after the storm?” For many of us, that demarcation also reflects our physical relationship to the city—it is a question that often means Was that before or after I was forced to leave my home? Because I was a senior in high school when Katrina made landfall and because I finished school in another state, I never lived in New Orleans again. When I came back home for the holidays, I would stay on a pullout couch in the guest room.

Sometimes I think of what that year could have been had Katrina never happened. What it would have been like to be the captain of my soccer team during my final high-school season. What it would have been like to attend homecoming and prom with friends who had known me since I was a toddler. And what it would be like now to bring my children back to the house that I grew up in.

But I still have my memories of growing up in a city unlike any other in the world—a city that some said should not have been rebuilt. Twenty years later, New Orleans is still here. I’m able to make new memories with my own children: taking them to Saints games in the Superdome, as my father took me. Playing with them on the trees in City Park, the way my mother did with me. Eating the cake I loved from Adrian’s at my parents’ dining-room table—even when their taste buds don’t match up with my nostalgia. My daughter said she wished the cake were chocolate. My son prefers ice cream.

This article appears in the September 2025 print edition with the headline “Going Back.”

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed