This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway turned 100 this spring—not quite double the age of its protagonist, Clarissa Dalloway, who, as Woolf writes, “had just broken into her fifty-second year.” The book pops up less frequently on lists of the best fiction of the 20th century than James Joyce’s Ulysses, the libidinous classic to which Dalloway is often read as a side-eyed response. But I would put it right alongside that epic, near the very top, because it rewards rereading at various stages of life. As Hillary Kelly wrote this week in The Atlantic, “The novel’s centennial has occasioned a flurry of events and new editions, but not as much consideration of what I would argue is the most enduring and personal theme of the work: It is a masterpiece of midlife crisis.”

First, here are five new stories from The Atlantic’s books section:

The tech novel’s warning for a screen-addled ageThe Islamic Republic was never inevitable.Memoir of a mailmanEight books for dabblers“Faith,” a poem by Kevin Young

I first encountered Mrs. Dalloway, as many readers do, when I was in college, and it lit up my still-maturing brain. Like Ulysses, it takes place over a single day in June, pulling together a group of narrative perspectives to capture the physical and mental cacophony of modern city life. Its characters include Clarissa, who is about to host a high-society party, as well as Septimus Smith, “aged about thirty,” a veteran of World War I who ends up jumping to his death. The juxtaposition of life and death, war and peace, youthful fury and wistful wisdom, reflects Woolf’s ambition to deploy stream-of-consciousness style in the service of deep emotional realism. One of the first works of literature to depict what would later be known as PTSD, it is in part about the dangerous passions of youth.

And yet its title character is 51, married to a politician, and worried that she has forsaken a more adventurous life. Woolf writes that Clarissa, setting off to buy flowers, “felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged.” I know the feeling—now. When I first read one of the book’s most pivotal scenes, in which Clarissa learns of Septimus’s death during her soirée, I interpreted the moment as the reality of war intruding on a bourgeois order oblivious to its own decline. It is that—but it is also the specter of mortality that underpins the anxieties of middle age. As Kelly reminds us, Clarissa thinks: “In the middle of my party, here’s death.” Yet this thought is immediately followed by an intense affirmation, Kelly writes: “She steps into the recognition that, despite the decisions she’s made, or perhaps because of them, ‘she had never been so happy.’”

Kelly finds parallels between this realization and a turning point in Woolf’s own life: At 40, in a moment of respite from her mental illness, she managed to write this book, and then her equally classic novel To the Lighthouse. This was, Kelly writes, “a season of fruitfulness” in which “she produced her most profound work.” At 21, I was ambivalent about Dalloway’s conciliatory ending, in which a woman keeps dread at bay by learning to revel in small and ordinary pleasures. But today, I look forward to the year, not far off, when I will be Clarissa’s age, so that I can read the book again, and see it with the kind of fresh eyes that only time and reading glasses can provide.

Illustration by Akshita Chandra*

Illustration by Akshita Chandra*

Mrs. Dalloway’s Midlife Crisis

By Hillary Kelly

Virginia Woolf’s wild run of creativity in her 40s included writing her masterpiece on the terrors and triumphs of middle age.

What to Read

The Right Stuff, by Tom Wolfe

Wolfe loved big, colorful characters, and he found plenty of them in the cadre of postwar American fighter pilots who helped develop supersonic flight—and, later, manned spaceflight. Wolfe’s subjects risked their lives in the skies over the California desert in military planes, then went on to join NASA’s Mercury program, becoming the first Americans in space. They quickly became Cold War celebrities whose virtues embodied a particular vision of heroism: competent, courageous, ready to lead the world to a new and limitless frontier. But in his account of the early space race, Wolfe contrasts their boy-band glamour with a more laconic aeronautical hero: Chuck Yeager, who broke the sound barrier while secretly nursing broken ribs and later pushed a juiced-up supersonic fighter beyond the edge of the atmosphere, barely surviving the ensuing crash. Skilled, relentless, and taciturn, Yeager embodied “the right stuff”—that hard-to-define quality that the boundary-breaking pilots and astronauts ended up prizing above all else. — Jeff Wise

From our list: Six books that explain how flying really works

Out Next Week

📚 The Unbroken Coast, by Nalini Jones

📚 Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State, by Caleb Gayle

📚 To Lose a War: The Fall and Rise of the Taliban, by Jon Lee Anderson

Your Weekend Read

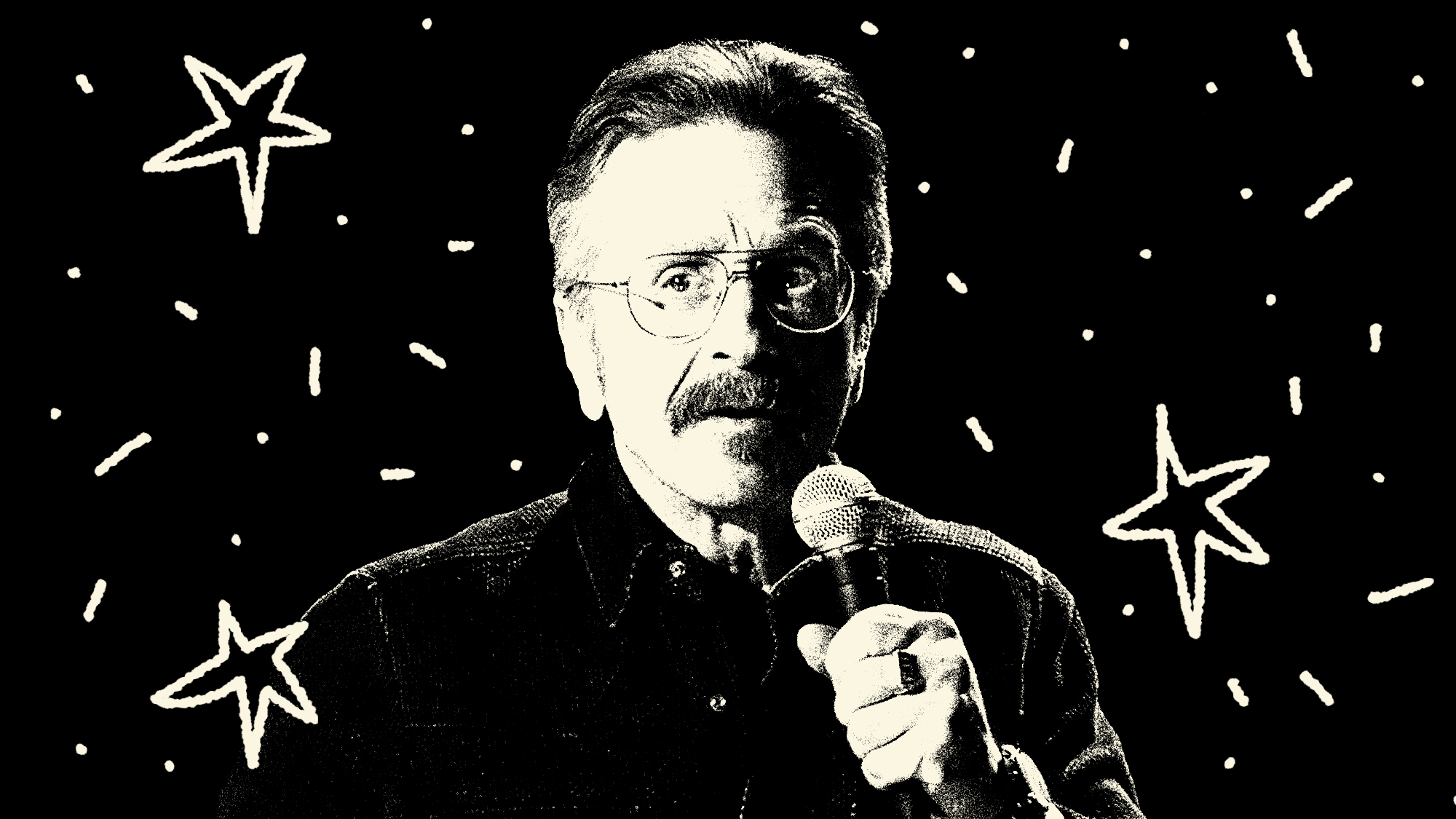

Illustration by Akshita Chandra. Source: Karolina Wojtasik / HBO.

Illustration by Akshita Chandra. Source: Karolina Wojtasik / HBO.

Marc Maron Has Some Thoughts About That

By Vikram Murthi

Back in the 1990s, when Marc Maron began appearing on Late Night With Conan O’Brien as a panel guest, the comedian would often alienate the crowd. Like most of America at the time, O’Brien’s audience was unfamiliar with Maron’s confrontational brand of comedy and his assertive, opinionated energy. (In 1995, the same year he taped an episode of the HBO Comedy Half-Hour stand-up series, Maron was described as “so candid that a lot of people on the business side of comedy think he’s a jerk” in a New York magazine profile of the alt-comedy scene.) But through sheer will, he would eventually win them back. “You always did this thing where you would dig yourself into a hole and then come out of it and shoot out of it like this geyser,” O’Brien recently told Maron. “It was a roller-coaster ride in the classic sense.”

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic*.*

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed