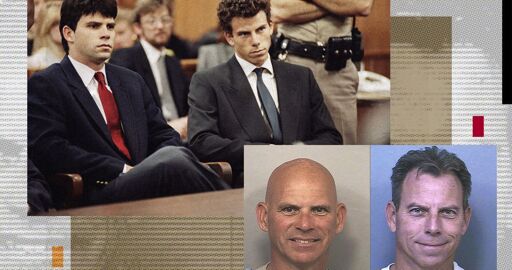

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: AP Photos, Mega

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: AP Photos, Mega

On Thursday, Erik Menendez will be escorted from his cell inside the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility outside San Diego to meet with a commissioner and deputy commissioner from the California parole board. The next day, his olderbrother, Lyle, will do the same. During what the board euphemistically refers to as a “conversation,” the Menendezes will be questioned under oath in the most deeply personal way possible about why, exactly, they shot their parents to death 36 years ago nearly to the day. “No court has ever heard the full story in this case, the depth and depravity of the abuse suffered by Lyle and Erik, and their remarkable journal of personal transformation,” their lawyers wrote in a recent court filing. The parole board will.

Originally condemned to life without parole, the brothers took a major step toward freedom in the spring when, over the furious objection of prosecutors, a Los Angeles judge resentenced them, clearing the way for this week’s hearings. Advocates for the brothers view them as the sort of trial that they never had, happening in an era when credible claims of sexual assault are taken more seriously than in the 1990s, when popular culture mocked the pair as a couple of spoiled narcissists who concocted fake abuse claims to get away with murder.

More recently, the brothers have gotten a second, more favorable look from the public after their lives were dramatized in an Emmy-nominated scripted series from Ryan Murphy and a documentary, both on Netflix. Today, Lyle and Erik’s story of victimization has created an outpouring of compassion. They have legions of TikTok fans as well as the support of nearly 30 extended family members and high-profile advocates, such as Kim Kardashian, arguing passionately for their release.

Getting parole isn’t a simple matter of demonstrating good behavior behind bars. While Lyle, 57, and Erik, 54, have both amassed impressive records of achievements during their incarceration, it won’t be enough; if the parole board does not believe they are radically honest in their account of the murders, they will almost certainly lose. The outcome of the proceedings may hinge on their ability to demonstrate sufficient “insight” into their crimes. This slippery, subjective test requires them to give an exhaustive account of what they did and what the parole board will accept as truthful and reliable evidence that they pose no risk to the public.

Their story that they acted because they believed that their parents were going to kill them after Lyle supposedly threatened to expose their father’s yearslong sexual abuse of Erik will be pitted against the Los Angeles district attorney’s argument that they killed their parents in cold blood to inherit a multimillion-dollar fortune, which proved successful with the jury that convicted them of first-degree murder in 1996.

Over a series of interviews this summer, lawyers for the Menendezes previewed for me how the brothers will testify before the parole board. They will admit that they told extensive lies to cover up acts that the lawyers have characterized in court filings as “heinous, cruel, and criminal” but will continue to insist that they believed they were in a life-or-death situation with no way out. In assessing the key question of their present risk, what matters is how much they have grown and changed, says attorney Cliff Gardner, a member of their defense team. “Thirty-five years of really extraordinary conduct speaks louder than the lies they told to avoid culpability at the ages of 18 and 21,” he says. “That is what maturity is.”

Exhaustive and invasive, a parole hearing is akin to an MRI of the soul. In addition to the hourslong interrogations of Lyle and Erik, the board will review tens of thousands of pages of transcripts, medical and psychological records, risk-assessment reports, expert declarations, commendations, letters of support, and the arguments of the brothers’ lawyers and the district attorney’s office, which is determined to keep them behind bars until they die. Critically, the parole board will have evidence that the jury did not. This includes dramatic new revelations that tend to corroborate Erik’s sexual-abuse allegations against his father and point to another alleged victim.

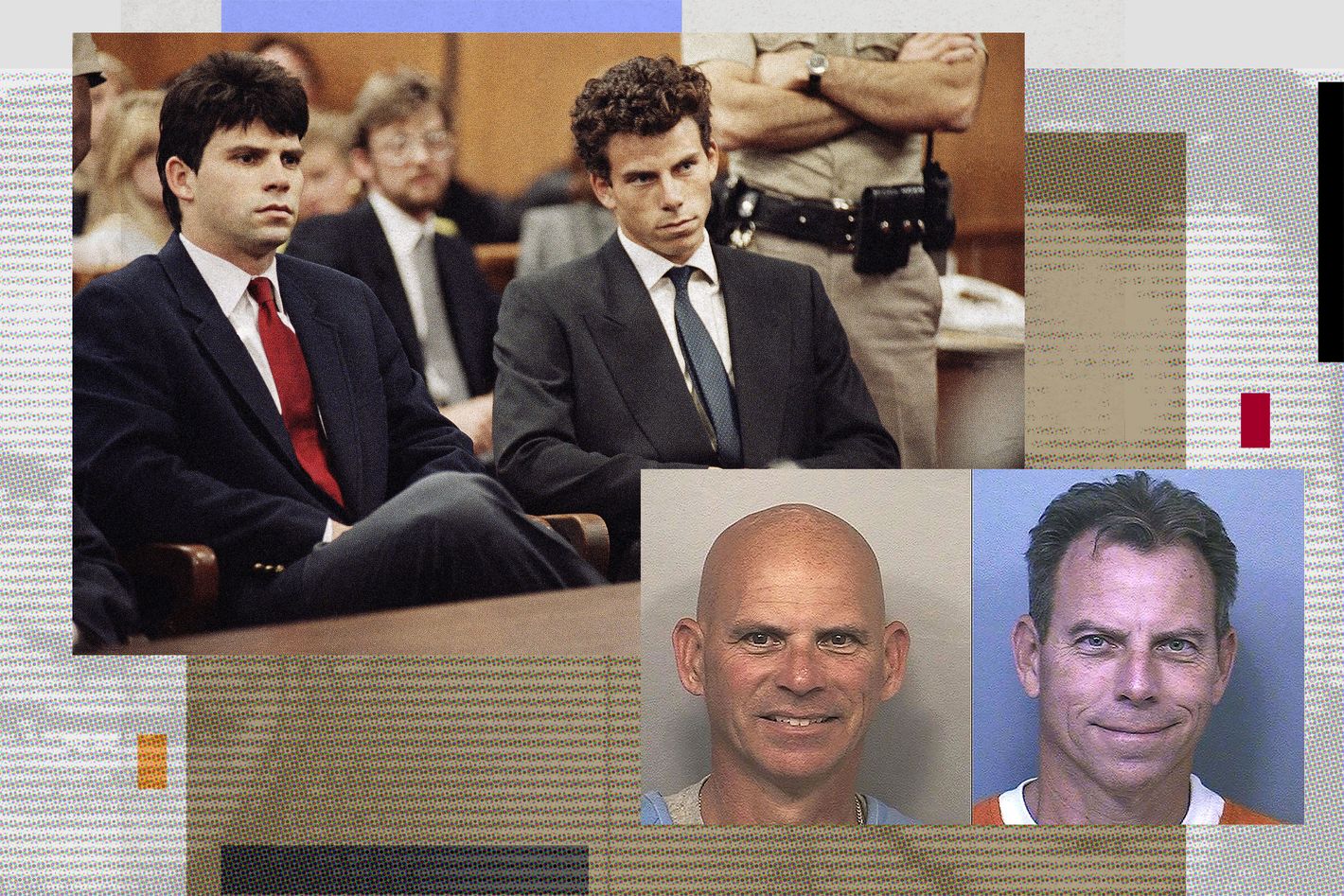

Photo: David Swanson/AFP/Getty Images

Photo: David Swanson/AFP/Getty Images

“As much as the crime repels, it attracts enormous interest,” says Kathleen Heide, a distinguished professor at the University of South Florida and one of the country’s foremost experts in parricide. Children who kill their parents generally fall into one of four categories, according to Heide: those who are in fear of their lives and desperate to end the abuse; those who are enraged with their parents, sometimes due to past abuse; those who are severely mentally ill and have lost contact with reality; and those who are dangerously antisocial, possibly psychopathic, and kill to get something they want, such as money or freedom. Where the Menendez brothers fall on that spectrum is a perennial subject of fascination and fierce debate. “What is going on that these boys who from the outside had everything — money, looks, opportunities — would do such an abhorrent thing?” as she puts it.

How the parole board answers that question and whether it believes that Lyle and Erik have taken complete accountability and have shown genuine remorse will play an important role in the decision. If the board finds them suitable for release, they could walk free as soon as October.

Such a previously unthinkable scenario has been made possible by major changes in the legal system over the past two decades. Beginning with the tough-on-crime era in the late 1970s, California prisoners serving life sentences had next to no chance of getting released. Even in the rare cases in which the board would issue a favorable decision, the governor was likely to reverse it.

The first change came in 2008, when the California Supreme Court held in a case called In re Lawrence that the heinousness of the offense, standing alone, was not a sufficient basis to deny parole. Following that decision, parole grants increased significantly. In 1979, only a single person was granted parole, but by 2019, the number had risen to 1,184. The period from 2013 through 2021 saw the release of 10,000 people sentenced to serve life terms, with a recidivism rate of less than 3 percent.

The brothers also benefit from a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions requiring special consideration for juvenile offenders. In 2012, the Court issued a landmark ruling that outlawed mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles and required that states provide them with “a meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.” Several years later, California fashioned a more lenient standard for “youthful offenders,” defined as anyone under the age of 26 at the time of the crime. In these cases, the parole board must assign “great weight” to the “hallmark features of youth” and take into account their diminished culpability. Ironically, given their current ages, they are also entitled to special consideration as elderly prisoners, requiring the parole board to assess how their ages, the amount of time served, and any physical health problems may reduce their risk of future violence.

But hurdles remain. On the same day that the California Supreme Court decided Lawrence, it held in a different case that a lack of insight was a sufficient basis to justify continued incarceration, citing a “rational nexus” between a failure to tell the full truth, atone, and accept responsibility with a risk of future dangerousness. Subsequently, demonstrating insight has taken on a central role in hearings and the board uses this reason to regularly reject otherwise compelling applicants. Even when the board grants parole, it’s up to the governor to allow it to happen. In the year following the decision, the governor invoked lack of insight a whopping 78 percent of times denying parole.

Gavin Newsom, the current governor, consistently invokes an offender’s lack of insight to explain his decisions reversing the board. The Menendez brothers may have reason to fear they are vulnerable on this front. The lies that they told after the murders were jaw-dropping. While the brothers plan to admit to many of those, prosecutors will argue that they continue to lie about why they killed their parents, a fabrication the state maintains is so fundamental it goes to the core of who they really are: dangerous, unrepentant killers.

The 911 call came at 11:47 p.m. on Sunday, August 20, 1989. Breaking down as Erik sobbed in the background, Lyle told the operator, “Someone killed my parents.” Police arrived at their Beverly Hills mansion to find Jose and Kitty dead in the family room, their bodies torn apart by more than a dozen shotgun blasts fired at close range. Lyle and Erik claimed that they discovered their parents after returning home from a night out and theorized it was a hit job related to their father’s work as a Hollywood entertainment executive. They were setting up an alibi. As an appellate court later wrote, “The gory scene of slaughter of Jose and Kitty Menendez is consistent with the notion that the killings were carried out with the false Mafia story already in mind.”

For months, they played the role of grieving, terror-stricken survivors. Lyle eulogized his father at the funeral, and he and Erik even hired a bodyguard for protection from the hit men they claimed were responsible for the murders. Meanwhile they used the $650,000 payouts from their parents’ life-insurance policies to buy Rolexes, luxury cars, and real estate. The brothers’ involvement might never have been uncovered — they collected all the shell casings, threw away their bloody clothes and shoes, and tossed their shotguns over a cliff — but for Erik’s guilt-ridden confession to his psychotherapist.In one of a series of morally and ethically questionable decisions, Dr. Jerome Oziel brought in Lyle and recorded the brothers admitting to the murders. Lyle said that their father’s relentless domineering ways made him “impossible to live with,” and Erik said that their mother could not survive without him. Neither mentioned abuse.

It was while they were in jail awaiting trial that the brothers began describing their father’s predations, first to defense experts and then to their lawyers. Their claims were stomach-turning. Lyle stated that beginning when he was 6-years-old, Jose groomed him with massages and then began to fondle him, force objects inside of him, and eventually to rape him. The abuse stopped when Lyle was 8, and, he said, his father turned to his younger brother who recounted similar sadistic behavior over a longer span of time. They said the abuse continued for a decade, with the last assault approximately ten days before the murders. Both brothers described their mother, Kitty, as unstable, violent, and complicit in their father’s crimes.

Though the double murder of two Beverly Hills parents made headlines, the story became an international sensation after their children were charged. Before it was eclipsed by O.J. Simpson’s legal odyssey a few years later, the case was called “the trial of the century.” These were the early days of Court TV, and it was one of the first major trials to be televised. The wealthy, handsome brothers and their story of hidden, horrific abuse riveted the more than 1 million people who tuned in each day. Much of the coverage in 1993 was unsympathetic. Reporters, TV anchors, talk-show hosts, and comedians treated Lyle and Erik’s claims of abuse as rich fodder for ridicule. In a now-infamous Saturday Night Live sketch, John Malkovich, playing a tearful Lyle, and Rob Schneider, playing a puppyish and equally sniffly Erik, say that the murder was committed by fictitious identical twin siblings Danny and Jose Jr., who were never allowed to have their existence officially recognized because Jose decided that “they were weak and not good tennis players.” As the brothers break down in crocodile tears, the chyron reads “They stood to inherit the sum of $14 million.”

Photo: Al Levine/NBCUniversal/Getty Images

Photo: Al Levine/NBCUniversal/Getty Images

Presiding over the trial was Judge Stanley Weisberg, who had overseen the embarrassing across-the-board acquittals of the four LAPD officers who beat Rodney King nearly to death several years earlier. The Menendez jury heard extensively from the brothers as well as from their cousin Diane VanderMolen, who testified that Lyle told her when he was 8 that Jose was sexually abusing him. Another cousin, Andy Cano, testified that Erik told him that his dad was touching his penis and about the ominous “hallway rule,” which Kitty strictly enforced to bar anyone from being on the same floor with Jose when he was alone with one of his sons. Multiple experts testified that the sex abuse had a deleterious effect on the boys’ psyches, turning them into fearful, disempowered, battered children.

The brothers’ team never claimed innocence, only lesser culpability, arguing that their clients’ trauma-scarred psyches made them sincerely believe their lives were in grave danger. During a case in which the prosecutors sought the death penalty, the defense urged the jurors to embrace a jury instruction on “imperfect self-defense.” Leslie Abramson, Erik’s attorney, distilled the outcome to two stark choices in her closing argument: Either “everything we have told you is not true,” or the murders were “done in a state of fear. And if that is true, there is no malice, and it can only be manslaughter.” After a month of deliberation, Judge Weisberg was forced to declare a mistrial. The brothers had separate juries and both had deadlocked, essentially split down the middle on their options.

The second trial beginning in 1995 was markedly different. Jury selection began eight days after Simpson’s jaw-dropping not-guilty verdict, and the pressure to lock up the perpetrators in at least one L.A. “trial of the century” had ratcheted up. This time, Judge Weisberg kept out much of the evidence of sexual abuse and physical violence and refused to allow the jury to consider imperfect self-defense. He also excluded VanderMolen’s testimony about Lyle’s confiding his abuse to her and barred most of the experts’ evidence. Cano testified again, but without supporting testimony, the prosecution easily dismissed him as a liar. A decade later, a federal judge assigned to one of the brothers’ failed appeals called the second trial “distasteful,” filled with rulings reverse-engineered to “jimmy things and see if we can get a conviction some other way.” Gardner, who was appointed to represent Lyle for his appeal in 1996, says, “They basically had no defense in the second trial.”

Los Angeles district attorney Nathan Hochman is convinced the second trial was fair and the brothers’ confessions to Dr. Oziel, which did not claim self-defense or sexual abuse, should be believed. Recent court filings by the prosecution emphasize that the allegations of abuse and imminent peril arose only after they had been charged, jailed, and were grasping for a lifeline. “The true mind-set of the Menendez brothers would have gotten them the death penalty, and if they wanted to get off, they had to come up with something a lot better,” Hochman tells me.

But when I ask him if he believes that the Menendezes were lying about having been sexually abused, Hochman responds immediately: “I never said that.” His position is that the abuse and the murders are unconnected. The brothers’ insistence that they acted in self-defense of imminent harm is “a total lie,” he says, because their actions beforehand — buying guns, learning to fire them, and creating an alibi — pointed clearly to calculated, deliberative planning.

“Nonsense on stilts. You cannot decouple the sexual-abuse claims from the imperfect self-defense claims,” Gardner says, adding that Hochman’s attempt to pull them apart “betrays a lack of insight” into the case. He takes issue with the prosecution’s extensive efforts to challenge the veracity of the Menendezes’ story of abuse, pointing out that victims often tell their stories with imperfect recall and in piecemeal fashion after years of silence or denial. “That is something that the DA’s office absolutely knows from their years of handling these cases. Victims don’t spill their secrets immediately; it takes time for them to open up and be that vulnerable.”

The battle over the brothers’ culpability boils down to a willingness to understand their conduct through the prism of severe and chronic childhood sexual abuse and what experts say is its distorting effects on brain development and the ability to think and behave rationally, particularly when the victims are still relatively young and dependent on their abusers. More than the specificity of the allegations, it is this fundamental contradiction that has made the Menendez case so compelling for the past four decades: How could two brothers annihilate their family and then argue convincingly that they are victims, too?

After Andy Cano died in 2018, a photocopy of an undated letter handwritten by Erik was found among his possessions, which his lawyers claim was clearly written months before the murders. Addressing his father’s sexual abuse, Erik wrote to his cousin, “It’s still happening, Andy, but it’s worse for me now than before.” Tortured by sleeplessness and anxiety, Erik confided, “I never know when it is going to happen and it’s driving me crazy. Every night I stay up thinking he might come in.” He added that he was too afraid of his father to tell anyone: “He’s crazy! He’s warned me a hundred times about telling anyone especially Lyle.”

The evidence could be crucial at their parole hearings, because it corroborates the brothers’ story of abuse and fear for their lives. Already, their lawyers have fashioned the letter into a separate pleading, called a habeas corpus petition, to void the murder convictions entirely.

That’s not all. In 2023, Roy Rosselló came forward to say that Jose had drugged and raped him in 1984, when he was a member of the popular boy band Menudo and Jose was an executive at RCA Records. In a sworn declaration that the Menendezes’ attorneys submitted to the court in the habeas petition, Rosselló recounted an evening when he met Jose in his limousine in New York City, was taken back to a house in New Jersey, plied with alcohol, and raped. Rosselló said he lost consciousness and woke up bleeding from his rectum.

Had the jury heard this evidence, the defense says, it would have severely undercut the prosecution’s dismissal of Cano as a liar. More fundamentally, Erik’s letter and Rosselló’s declaration cast into grave doubt the state’s argument that the brothers provided “no corroboration of sexual abuse” and no reason to fear their father because Jose was “not a violent or brutal man.”

Last month, the brothers won an incremental victory when the judge hearing the habeas petition ordered the prosecution to file a formal response to justify leaving their convictions intact. On August 7, the district attorney’s office filed a 132-page response, arguing that the newly proffered evidence is of suspect origin, untimely, and “in full alignment with Petitioners’ documented history of deceit, lies, fabricating evidence, and suborning perjury in this case.” A ruling from the court as to whether the brothers receive an evidentiary hearing — with the possibility that their convictions could be wiped away if their claims hold up — could come any day.

But first, they will face the parole board and the force of the DA’s argument that their continued insistence that they acted in imperfect self-defense is the very definition of a lack of insight given the extensive evidence pointing to premeditation. This includes the confessions to Dr. Oziel, in which, according to the prosecution, Lyle and Erik were “unspeakably callous in describing their decision-making and their state of mind.” By maintaining that they were driven to kill by a sincere if misguided belief that they were in imminent danger from Jose and Kitty, the brothers were proving their unsuitability for release, Hochman says. The heart of Lyle and Erik’s stories is more than a lie, he tells me, it is proof of “a ticking time bomb in their personalities that has not been diffused or eliminated.”

Demonstrating insight and acceptance of responsibility for parole do not require parroting the state’s version of the crime though. Under California law, only an “implausible” account of one’s crimes can be used as a basis to deny parole, and Gardner says that “there is nothing implausible about a theory that half of both juries accepted at the first trial.”

Hochman also disputes that Lyle and Erik’s conduct in prison has been extraordinary. While conceding that they have made “great strides,” he also points to the recent comprehensive risk assessment prepared by prison psychologists, which found that both brothers pose a “moderate” risk of violence rather than the coveted low-risk categorization. He lists their history of rule violations, which include Erik’s unlawful possession of a cell phone and what Hochman says were his attempts to induce other prisoners to take the fall for it as well as Lyle repeatedly failing to report for a work assignment.

“They broke the rules, and they know that they broke the rules,” says Michael Romano, who directs Stanford Law School’s Three Strikes Project and is a member of the Menendezes’ defense team “That was a mistake. But Lyle not showing up for work or Erik having a cell phone? That doesn’t mean that they are dangerous.”

A double parricide involving two biological siblings is so abnormal that it happens only very rarely in the U.S. The singularity of the crime makes it hard to compare Lyle and Erik meaningfully with other offenders because so few children who experience sexual abuse go to the extreme of killing their parents. When I spoke with Carlos Cuevas, a psychologist and professor of criminology at Northeastern University who has written about the Menendez brothers, he acknowledged as much. But he added that “just because they did this really horrible thing does not mean that they weren’t victims. Many perpetrators are abuse victims — these two things often coexist within a single person, and that is the next level of awareness that we as a society need to reach. We have to accept that victims and perpetrators are a highly overlapping group.”

A parole hearing is like a trial in certain fundamental ways. Both the defense and the prosecution will get to ask pointed questions of the Menendez brothers when the commissioners are finished with theirs. There will also be closing arguments. The state’s argument is likely to employ much of the rhetoric that succeeded in the second trial, arguing that the brothers are, in Hochman’s words, “lying murderers” still unwilling to admit that they shot their parents to death for money and for no other reason. The defense will stress that the brothers worked hard to better themselves during the bleak, decades-long period when they had no chance of ever getting out of prison. “Somehow, they were able to find some dignity, hope, positivity, and purpose to better themselves,” Romano tells me. “I find that completely remarkable and admirable.”

If TikTok had a vote, the brothers would have been released months ago as victims who have served more than enough time. But the legal system is more rigid and sclerotic, historically hostile to such a characterization of offenders who commit crimes as shocking and brutal as theirs. Cuevas tells me that the case creates “cognitive dissonance” in a system that reflexively sorts people into categories: good/bad, law-abiding/criminal. Their lawyers believe that the parole board will reject the state’s black-and-white narrative and offer these middle-aged men a second chance by accepting that the truth exists in shades of gray. It is by telling a no-holds-barred story of what they say really happened inside their home and of their lives since — painful, ugly, tragic, and, in the end, redemptive — that the defense believes Lyle and Erik Menendez can finally win their freedom. Their success may depend on whether the legal system has transformed as radically as the brothers insist that they have.

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed