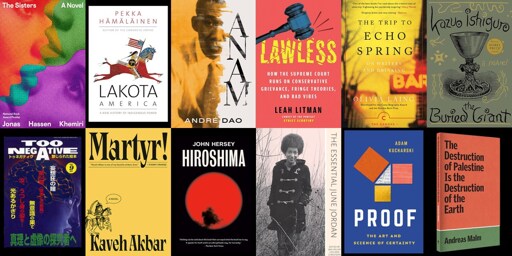

Nonfiction

“Proof: The Uncertain Science of Certainty Book,” Adam Kucharski (2025)

My summer reading was a little unusual this year, because I’m in the middle of writing a book, which is orienting my reading choices (alongside my nagging insecurities, etc.) The book I’m writing is about how our discourses around uncertainty (“these uncertain times” and so on) can risk distracting from some of the more pernicious certainties grounding this grim conjuncture — so I’ve been trying to keep vaguely abreast of the “uncertainty” literature circulating.

Most of it is the very sort of thing I’m arguing against — overtures to unending doubt, which fail to look at what gets held certain, which world-ordering structures get to resist doubt (e.g. borders, property relations, gender binaries), by whom, how, and to what ends. But a very nice, general reader book by mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, “Proof: The Uncertain Science of Certainty,” was a breath of fresh air.

In it, he looks at the historically, materially situated activities and assumptions involved, in fields from law, economics, medicine, statecraft, and more, in establishing proof and certainty. He uses great anecdotes and examples — like the time Kurt Gödel (founder of modern mathematics) in his 1947 U.S. citizenship interview declared that he had discovered the ways a formal fascist regime could be established in the U.S., not by a leader eschewing the Constitution, but relying on its inner contradictions.

I’m particularly thinking it’s a great gift for the vulgar positivists and bewildered liberals in your life, who would never read radical theory on truth production but might listen to a bestselling mathematician and epidemiologist. – Natasha Lennard

**“The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking,” Olivia Laing (2014)**I’ve re-read this book several times since it was published, and it never disappoints. “The Trip to Echo Spring” is beautifully written and profoundly idiosyncratic. It is deft literary criticism. But also an amalgam of biographies. And it’s a travelogue. And it’s also a memoir.

The book meanders in and out of the lives of six extraordinary writers — F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Berryman, John Cheever, and Raymond Carver — who were also extraordinary drinkers. It lists this way and that, wandering into Laing’s life too. Not every author is up to the task of writing about great writers, but Laing more than holds her own. Try not to salivate when you read this passage: “Click in a cube of ice. Lift the glass to your mouth. Tilt your head. Swallow it.” Try to convince your brain not to paint a picture after imbibing this line: “For years, I’d steered well clear of the period in which alcohol seeped its way into my childhood, beneath the doors and around the seams of windows, a slow contaminating flood.”

You don’t need to be a writer or a drinker to enjoy Laing’s book. But if you do happen to be one, either, or both, it’s an especially lovely book to sip and savor. “I’m taking a little short trip to Echo Spring,” says Brick, a character in Tennessee Williams’ Pulitzer-winning play “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” referencing his brand of bourbon. The book goes down just as warm and smooth — the literary equivalent of 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle. But the finish is not without bite. All six men were also laid low by drink-induced decline, dementia, and disease.

“I was beginning to think,” Laing writes, “that drinking might be a way of disappearing from the world.” It’s easy to disappear into the pages of “The Trip to Echo Spring,” and it’s uniquely satisfying as well. It’s almost as enjoyable as spending a weekday afternoon sipping an expertly crafted Old Fashioned at the St. Regis New York’s King Cole Bar, or at your favorite local bar, or at any old tavern, or on your front stoop.

Almost. – Nick Turse

**“Hiroshima,” John Hersey (1946)**August 5 and 9 marked 80 years since the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and it’s clear that our collective memory of the horror the U.S. government subjected the civilians of those cities to has greatly diminished. As tensions worldwide increase and the Trump administration waffles on its long-standing security commitments to allies, politicians of countries without nuclear weapons programs, including those of Japan, are reconsidering that stance.

That’s why it is so important that everyone reads John Hersey’s book “Hiroshima.” It first appeared as an article in The New Yorker — taking up the entire August 31, 1946, issue. Hersey’s account following six people who survived the A-bomb exposed the American public to the reality of what their government had done.

I first read it as an undergraduate student in a “Great Books of Journalism” class, and Hersey’s vivid descriptions of the aftermath have stuck with me since. This book is graphic, be prepared for that. But with 35 percent of Americans in June 2025 still saying the bombings were justified, compared to 31 percent who say it was unjustified (the rest “aren’t sure”), we owe it to the hundreds of thousands of people who died or suffered in the aftermath to be uncomfortable. No one should have to suffer like that ever again. – Chelsey B. Coombs

“Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power,” Pekka HämäläinenA gripping, if scholarly, take on the Lakotas that treats them as central characters rather than bit players. Recommended reading for a road trip through the Upper Midwest and Great Plains. – Matt Sledge

“The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth,” Andreas Malm (2025)“What, exactly, is it that ties the state of Israel and the rest of the West so closely together? What explains the willingness of countries like the U.S. and the U.K. to collaborate in genocide? Why does the American empire share Israel’s goal of destroying Palestine?” Malm addresses these questions by drawing a line connecting the destruction of Palestine to the U.S. and the West’s control and the extraction of fossil capital from the region, making the genocide of Palestinians a strategic part of U.S. foreign policy and also a point by which we began and continue to destroy the planet through fossil capital. – Jeehan Mikdadi

**“On the Hippie Trail: Istanbul to Kathmandu and the Making of a Travel Writer,” Rick Steves (2025)**Anyone who travels knows of Rick Steves, but “On the Hippie Trail” shows a totally different side of him. I loved seeing Rick not as the confident guide we know, but as a young, sometimes awkward backpacker trying to find his place among more seasoned adventurers. As a traveler, I loved this book because it captures that raw, unfiltered feeling of being young, curious, and totally open to the world. It’s part coming-of-age story, part snapshot of a very specific moment in travel history — a time where you could journey over land through Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan; a time when Western backpackers could freely travel through cities like Kabul, mingling with locals and other travelers over hashish and tea. It reminded me of why I love traveling: meeting new people, navigating the unexpected, and letting travel shift the way I see things. It’s not polished or overly romanticized, and that’s exactly what made it feel so real. – Lauren Schilli

“Lawless: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories, and Bad Vibes**,” Leah Litman (2025)**The summer has become a gloomy period among lawyers, as we wait for the U.S. Supreme Court to close out its session and release its final flurry of rulings. How did we get to the point where we refresh our feeds to see what’s left of bedrock constitutional precedent? Leah Litman, a law professor at the University of Michigan and co-host of the “Strict Scrutiny” podcast, unpacks the conservative turn on the SCOTUS bench in recent decades, blending legal history with her signature snark. – Shawn Musgrave

Fiction

**“The Buried Giant,” Kazuo Ishiguro (2015)**It’s a weird read. While it has a dragon and Sir Gawain, it is not a fantasy as much as an allegory framed like the Arthurian grail stories. I think the book is about deceit and betrayal on a macro and micro scale: entire nations and the people we love. It’s a sad, reflective book, like most of his works. – David Bralow

**“Anam,” André Dao (2023)**Ideology is too blunt an instrument for André Dao’s “Anam.” This is one of those meta-novels that uses the process of its own writing to propel the plot, slipping the reader between phases of empire via the narrator’s family research mission to Hanoi, interviews with his refugee grandparents in Paris, and distracted afternoons at Cambridge University, where he’s pursuing a degree for which he’s forced his tiny daughter and unhappy wife to move. At its heart is the narrator’s dead grandfather, a Vietnamese anti-communist who spent a decade imprisoned by the same regime over which the U.S. torched and poisoned the country and still failed to defeat, whose memory forces the narrator to grapple with his own left politics and his dissatisfaction with his family legacy.

Dao confronts that inherently egotistical fixation — a legacy — by having his narrator admit how exploring his family’s past has blocked his ability to prioritize a different extension of the self: his offspring. “How terrible has my pursuit of the past been,” he wonders, “if it has led to the total occlusion of the future?” His wife, the primary caretaker of his child, serves also as chief caller of bullshit: Challenging his patriarchal focus, she questions why the family story revolves around his grandfather rather than his grandmother. All storytelling is revealed as inherently reductive, the choosing of any main character as reliant upon the sidelining of others. Picturing his grandfather chained to the wall in a prison cell, the narrator admits: “I think that the image really is too reductive, victimising, gratuitous — basically that it’s tacky.” But it really happened, he thinks, despite any aesthetic objection, and despite the fact that both the family history and the narrator’s essentially self-centered fixation on it are inconvenient for his politics. “And if that really happened,” he allows himself, “then how can it not be at the heart of things?” – Maia Hibbett

“The Sisters,” Jonas Hassen Khemiri **(2025)**This family saga follows the lives of the three charismatic Swedish-Tunisian Mikkola sisters and a shy Swedish-Tunisian boy who grows up alongside them. Across decades and continents, the sisters are haunted by a family curse, while the boy — named Jonas Khemiri, like the author — attempts to reclaim the singular connection he felt to the Mikkola sisters as a child. The novel is told in six sections ranging from a year to a single minute. Through this structure, the author plays with the notion of time and expectations, reveals the identities we adopt and shed, and upends the sanctity of family legacies. It’s an elegant and compelling read, and you won’t even notice it’s over 600 pages. — Celine Piser

“Circe,” Madeline Miller **(2018)**I’ve read “Circe” multiple times, including this summer. It’s by the same author as “The Song of Achilles,” which I also loved. The real world can be a little dark, and this book is perfect Greek Mythology escapism. – Jessica Washington

**“The Boy and the Dog,” Seishū Hase (2020)**Friends recommended “The Boy and the Dog” after I told them I wanted to make a fictional short film about the adventures my pup would get into: traversing through California landscapes trying to find his way home, making friends both human and furry along the way. Hase’s novel traces the journey of another extraordinary dog, separated from his person after a devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

Known by many names, the dog is steadfast in his search, yet along the way he brings unexpected solace to the people he meets, whose own lives are full of chaos, drama, and the ordinary ups and downs life also brings. As Miwa, one of the book’s distinctive characters observes, “It’s your dog magic, I suppose. Dogs don’t just make people smile. They give us love and courage, too, just from being at our side.” – Laura Flynn

**“Operation Shylock,” Philip Roth (1993)“Martyr!” Kaveh Akbar (2024)**I would like to witness these two writers (or their doppelgängers) hashing it out in a talk-show format — Legacy! Identity! Generational trauma! Unreliable narrators! And of course, martyrdom! — much like the conversations imagined by the “Martyr!” protagonist in his attempts to fall asleep. – Fei Liu

**“The Oligarch’s Daughter,” Joseph Finder (2025)**I tore through this. It’s a modern-day spy thriller set in New York that puts a twist on Cold War intrigue. – Akela Lacy

Poetry & Art

“The Essential June Jordan,” by June Jordan **(2021)**When reading the poetry of June Jordan, I may be crying of heartbreak, laughing, teeming with rage, and abandoning my desk for the streets to join a protest all at once and in no particular order. Jordan wrote prolifically (28 poetry collections) about themes of love, home, politics, motherhood, and loss. But perhaps what sets her most apart in literary and American history is how truthfully she reckoned with our position in the imperial core. She recognized the United States as a nation built on genocide and slavery, but also as an actor of genocidal horrors on the other Black and brown peoples of the world — from U.S. ties to apartheid South Africa to its unconditional support of Israel’s occupation of Palestine — a politics steeped in unflinching global solidarity. In her 1985 poem “Moving towards Home,” Jordan intimately embodies this solidarity: “I was born a Black woman / and now / I am become a Palestinian.” And she asks us to undergo a similar reckoning, by first turning toward the comfort of our “living room … where my children will grow without horror,” turning toward ourselves.

Following the U.S. bombing campaign of Iraq, she wrote in her 1997 poem “The Bombing of Baghdad,” which I read as a prescient indictment on neoconservatism that continues to color U.S. foreign policy: “And all who believed that holocaust means something / that only happens to white people / And all who believed that Desert Storm / signified anything besides the delivery of an American / holocaust against the peoples of the Middle East / All who believed these things / they were already dead / They no longer stood among the possibly humane.”

When my writing, whether journalism or poetry, feels stuck or stale, reading June Jordan’s poems offers me a path back to myself and toward the urgency of liberation — that is, toward something ultimately affirming of life. In “The Bombing of Baghdad,” she ends her poem with these lines: “And here is my song of the living / who must sing against the dying / sing to join the living / with the dead.” – Jonah Valdez

**Too Negative**Too Negative is a ’90s art zine from Japan. A typical issue is a carnivalesque cavalcade of the Chapman Brothers, Manuel Ocampo, and Joel-Peter Witkin, all interspliced with tabloid grotesquery and vintage medical ailments. The constant confabulatory barrage of de-formation bubbles forth a monstrous in-between sensationalism of both ultra- and non-humanism. Recommended for daily nightly consumption to make the earthly news cycle we’re exposed to more palatable — just go ask Alice’s mangled torso, “after such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling down stairs!” – Nikita Mazurov

The post What The Intercept Is Reading appeared first on The Intercept.

From The Intercept via this RSS feed