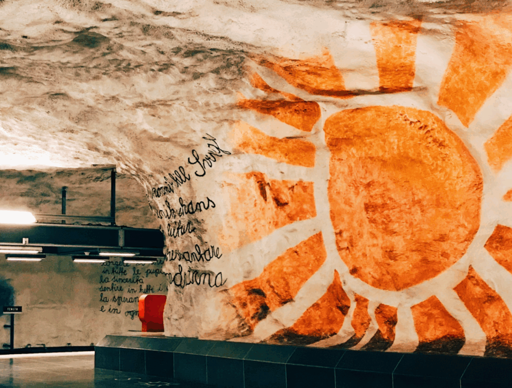

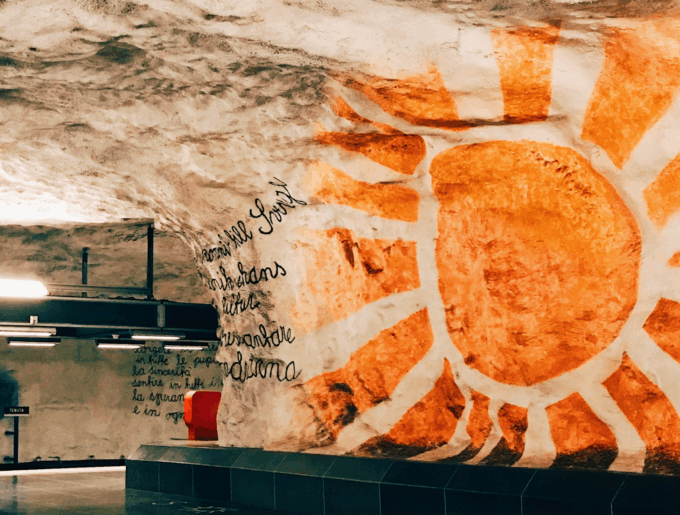

Photo by Fred Rivett

Much judgement of the UK drifts steadily westwards, crossing the Atlantic in fleets of think-tank reports, news magazine features, breathless cable bulletins, and populist asides from Trump, Vance or Musk. London struggles, we are told, the UK shrinks, immigration this, immigration that. It feels only right, then, that occasionally we should return the compliment, offering in this instance a kind of summer report card in the opposite direction. For from this side of the ocean, the US looks to us less a republic restored these days than a republic rehearsing the same act, louder, brasher, and infinitely more troubling or grim second time around.

It was called policy. As if there were somewhere a conclave of earnest men in pressed but probably dated khaki murmuring over spreadsheets, calculating trade balances with the sobriety of accountants. But this, in fact, was no policy. To us over here at least, it seemed like a tantrum disguised as statecraft. Especially for those of us with so many great friends in the US. For those of us with, if you like, an American bent.

Come January 2025, and Donald J Trump once more in the White House, radiating what his supporters like to call “glory” but what others recognise as a kind of radioactive presence—dangerous, unstable, impossible to ignore. His first act was not reconciliation, not rebuilding alliances, but tariffs, as everyone knows. Twenty-five per cent on Canada and Mexico, ten per cent on Canadian oil. A flourish of rhetoric as wide as the Rio Grande. (Rio Bravo, as Mexicans famously and admiringly call it.)

In Ottawa, they retaliated, politely, but with steel. Counter-tariffs, boycotts, the bland but lethal vocabulary of international relations — “grave concern”, “profound disappointment” — that in diplomatic code meant we are done here. In Mexico, the response was even starker. Polling suggested a colossal ninety per cent had no faith in Trump, a percentage so absolute it might have been lifted from a Gabriel García Márquez novel as magical realism tricked into political fact.

Europe watched with all the bemused horror of an aunt observing a favourite nephew implode. Brussels cafes and Berlin ministries muttered about the US’s “Suez moment”. The deal Europe signed with Washington — reciprocal tariffs, heavy investment obligations, energy concessions — looked less a contract between allies than tribute paid to an unpredictable overlord. We Brits signed as well, customarily stiff-lipped, consoling ourselves with the thought that at least this time the humiliation of indignity was shared.

And then, as if scripted by an ousted satirist, came Alaska. Vladimir Putin, his very self, appearing in Anchorage — half theatre, half provocation, conspicuously pale, unusually upbeat — describing his presence as a “peace mission”, even as Russian submarines nosed the Aleutians. Washington blustered, then hesitated, then did nothing. For allies, watching perplexed from across a storm-skimmed Atlantic, it was disconcerting in the extreme. Was this a stunt? Or was the Cold War back, this time played out like fur hats and TikTok filters on a loveless piece of track?

Meanwhile, chaos accumulated either side like dirty snow. The home and workplace of John Bolton, himself plucked from a particularly musty chapter of American neoconservatism, was suddenly raided — retribution as reprimand? Ghislaine Maxwell, a reviled Brit found guilty of recruiting and trafficking young girls to be sexually abused by Epstein, was quietly moved to a “lighter” prison, a decision that set the tabloids alight over here. Yet this appeared to elicit little more than a shrug from official Washington.

And in California, Gavin Newsom’s candidacy began to crystallise into something perhaps only briefly more spiky. A slick, tanned foil to Trump’s thunder, a Netflix match-up, or mash-up, that played as Dynasty versus Apocalypse.

Basically, the mood on the streets of US cities appeared to us over here less dramatic than quietly menacing. Soldiers, well familiar to us, patrolled not Kabul but LA, not Fallujah but DC. We were rubbing our eyes in disbelief, while dodging further US barbs ourselves. The justification, or so we read, was riots, tariffs, inflation, policing, take your pick. But the images that flickered across our European screens felt like madcap dispatches from a new dystopia. We saw presumably engine-warm Humvees idling in suburban car parks, armoured vehicles stationed outside Walmart, Americans, again, calling it “policy”. We did not see many actual faces. They were for the most part hidden. We, squinting from afar, saw it as martial law with chips.

Globally, the story soured, too. Aid to Kyiv was pared to the bone. Conveniently for Putin, the US blocked Ukraine from using US-supplied long-range missiles to strike targets inside Russia. This was supposed to get the Russians to engage in peace talks. Trump’s old admiration for Putin, however, seemed to have more than resurfaced, hesitation replacing deterrence. China, by contrast, was smiling, albeit quietly. Playing jazz with the yuan, improvising while Washington hammered out its new tune. While Washington withdrew, China opened like a giant ledger of commercial haikus. Despite Trump’s tariffs, Beijing negotiated reductions, posted stronger GDP figures, expanded ports in Africa, AI labs in Dubai, and Sino-French trade centres in Lyon, even if the UK was still undecided on Chinese plans over a “secret basement” in their London super-embassy.

Polls told the tale in what were seen as funereal bar graphs. Pew found that a massive 82 per cent of surveyed nations held a negative view of Trump — more disliked globally than Putin, even than Assad had been. In Canada, favourability towards the US plummeted from 52 to 19 per cent in half a year. In Europe, the figures were scarcely better. Trust had not just declined, it had collapsed.

The exits came swiftly. Paris Agreement, WHO, Human Rights Council—swept away on day one. Unlike the sudden closure of the many USAID projects in the poorest parts of the world, these withdrawals did not transform global institutions overnight, but they left scars, symbolic wounds that spoke of a world order dumped by one of its chief architects. The response was like a cultural boycott. Canadian shelves emptied of Coca-Cola and Nike, European airlines slashed routes to the US, and even Tesla — once a symbol of Silicon Valley’s aspirational cool — saw European sales fall by nearly half. Elon Musk’s expression in the face of this resembled a soufflé omelette dropped on a kitchen floor, or the Norwegian’s face when suddenly refused entry to the US on the grounds of a JD Vance face reincarnated as a balloon on his phone.

Africa’s picture was more complicated. In Nigeria and Kenya, polling still showed majorities expressing confidence in Trump, upwards of seventy per cent. Perhaps this was pragmatism, or the peculiar allure of a leader who seemed to bend the world to his will. Machoism? Is there even such a word? No, I don’t mean machismo. In the Middle East, however, his transactional embrace of strongmen further eroded the already fragile notion that the US still spoke for rights, for rules, for anything beyond immediate deals.

North Korea received its ritual performance of summits, photo-ops, exchanges of stiff but absurdly affable grins between Trump and Kim Jong-un. No North Korean warheads dismantled, no arsenals reduced. For us, there was just surprise at the lack of US concern over North Koreans fighting Ukrainians. Possibly as many as 15,000 already sent, with almost 5,000 casualties. Meanwhile, in Brussels, the Sentix index — a gnomic but widely watched gauge of investor confidence — tumbled from 4.5 to –3.7. Economists — of which I am decidedly not one — wrung their hands. Xi Jinping, inscrutable as ever, simply waited.

Whispers at the same time intensified. Axis of Upheaval. Russia, China, Iran, North Korea again — strange bedfellows, learning to share a shadow. They were not allies in the sense that the Atlantic alliance once was. But they were united in opposition, opportunistic in the unanticipated gaps left behind by American inconsistency.

Through it all, the US remained what it has long been. Powerful. Tanks, carriers, nukes, cash. An apparatus of hegemony, intact. Yet power without trust is presumably brittle. Had not Washington just stomped across the dance floor of diplomacy until no one really wanted to dance with them anymore? Allies hedged. Enemies smirked. Pax Americana became a ghost, a presence felt more in absence than in action, muttering about rules long since abandoned.

And yet. And yet.

Even from here, even now, one cannot afford to dismiss the US. In London pubs and Berlin dormitories, Nairobi start-ups and Mumbai cinemas, the US still lingers as an idea as much as a place. A nation that built universities, even if attacking them now, wrote so much music, sent rockets skywards. A country that, at its best, should feel less like a bully than a beacon. Many of us still dream in the abstract of Route 66, of $241 billion a year given by US philanthropists, of a republic that might once again redeem itself through reinvention.

“You can’t go home again,” as Thomas Wolfe used as a book title. But perhaps the US can, not to some halcyon past, but to the better angels of its own mythology. The artist David Wojnarowicz used successfully to insinuate American angels into otherwise dark work. Kerouac, arguably, too. Gary Snyder, certainly. One is still thinking reinvention here, resilience, the belief in nature and sweet redemption.

Until then, dream on. We, for our part, will continue to watch from across the water, keeping our heads down at times, knowing that America’s talent for reinvention has never failed it for long. Whether the next reinvention will be towards brilliant light or even darker shadow is another question. One thing is for sure: US criticism, for some reason, will keep coming our way.

The post Summer Report Card appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed