Global political history is punctuated by state entities that, after vanishing from the international stage, have reemerged in new forms—sometimes radically transformed, sometimes strikingly faithful to their origins. These revived states—polities that have undergone phases of dissolution, fragmentation, or annexation before regaining effective sovereignty—offer a privileged lens to examine the intermittent nature of statehood. Far from being a permanent attribute, sovereignty reveals itself as a fluctuating condition, subject to temporary suspensions, territorial redefinitions, and identity reactivations.

I co-developed a digital mapping tool called Phersu Atlas between 2020 and 2025, which enables navigation through tens of thousands of states spanning from 3499 BCE to 2025 CE. Its use allows for the possibility of identifying recurring patterns and dynamics that illuminate the problem of intermittent statehood with precision.

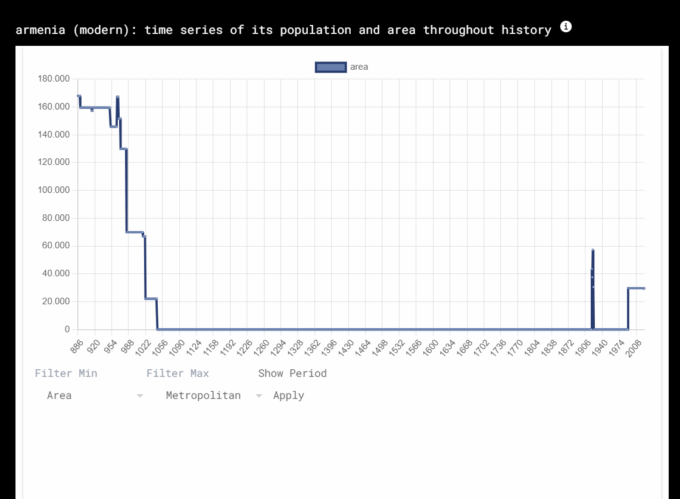

To illustrate, I’ve chosen the cases of Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland. These existing states share a history marked by porous borders, subjugation to external powers, and a resilient identity. Through the analysis of time series data on population and territorial extent, as well as the infographics and interactive maps provided by Phersu Atlas, the aim is to explore the dynamics of state suspension and reemergence, highlighting the conditions under which latent sovereignty can once again materialize as a recognized political entity.

These cases do not merely represent a return to sovereignty, but rather full processes of identity and institutional reactivation. The rebirth of the state entails the reconstruction of borders, symbols, and shared narratives—often in contexts of deep geopolitical instability. The ability of people to transform historical memory into a political project is what distinguishes mere cultural survival from true state revival.

In approaching these three historical cases, one can already identify recurring factors that have played a crucial role in preserving identity. Notably, the early development of a national language (accompanied by a robust literary tradition), the adoption of a distinct religion, and the frequent recourse to acts of explicit rebellion are common traits found among all states that have experienced a historical “revival.”

Despite centuries of foreign domination and political fragmentation, Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland have preserved their national identities through a strong continuity of culture. Language played a central role in this process: Armenian, with its unique alphabet created in the fifth century, cemented the cohesion of the people even during its diaspora; Vietnamese, though influenced by Chinese, retained its own phonetic structure and an autonomous writing system—first through Sino-Vietnamese characters, later through an adapted Latin alphabet; Polish, having survived the partitions and even after being banned in certain regions, remained the vehicle of literature.

Writers such as Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński composed works that not only preserved the Polish language but also nourished the national imagination. Polish Romantic poetry became a tool of resistance, capable of keeping the idea of a homeland alive even in the absence of a state.

Literary and philosophical production served as a guardian of memory: from Armenian epic poems to Polish patriotic verse to Vietnamese Confucian texts, each culture found refuge and a form of resistance in the written word. In all three cases, religion further reinforced identity: Apostolic Christianity in Armenia, Buddhism and ancestor worship in Vietnam, and Catholicism in Poland. These elements functioned as invisible pillars, capable of sustaining the nation even when the state itself had ceased to exist.

In the process of cultural survival that accompanied the disappearance and reappearance of the state in Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland, certain literary works acted as true bastions of ethnic identity, capable of preserving memory and reinforcing a sense of belonging. In Armenia, The History of the Armenians by Movses Khorenatsi, composed around the mid-fifth century (circa 440–470 CE), provided an organic narrative of the Armenian people’s origins, weaving together myth, genealogy, and history in a text that withstood Persian, Arab, and Ottoman dominations. In Vietnam, the poem The Tale of Kiều by Nguyễn Du, written between 1813 and 1820, embodied the cultural soul of the nation during a period of transition and vulnerability, elevating the Vietnamese language and Confucian values as symbols of moral and identity-based resistance. In Poland, Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz, published in 1834 in Paris during the author’s exile, represented an act of nostalgia and imaginative reconstruction of the lost homeland, strengthening the Polish language and national sentiment at a time when the state had been erased from the map.

Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland have each expressed, throughout their histories, a tenacious will for national emancipation, manifested through patriotic movements rooted both in antiquity and modernity. In Vietnam, as early as ancient times, the famous rebellions of the Trưng sisters (40–43 CE), who led an uprising against Chinese domination, and that of Lady Triệu in 248—a heroic figure who defied occupation with strength and charisma—stand as foundational episodes deeply embedded in the collective memory. These events foreshadow a long tradition of resistance that culminated in the 20th century with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, which spearheaded the struggle against French colonialism and later against American intervention during the war of reunification.

In Armenia, resistance took various forms: from medieval uprisings against Arab and Seljuk rule to the nationalist movements of the 19th century, such as the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (“Dashnaktsutyun”), which fought for independence in 1918 and later against Sovietization.

In Poland, the insurrectionary tradition is equally profound: from the uprisings against the Russian Empire in the 19th century (1830 and 1863), to the heroic Warsaw Uprising of 1944 against Nazi occupation, and finally to the “Solidarność” movement of the 1980s, which led to the fall of the communist regime in 1989. In all three cases, rebellion was not merely a political response but a profound expression of national identity.

Armenia—Intermittent Sovereignty and Ancient Imperial Echoes

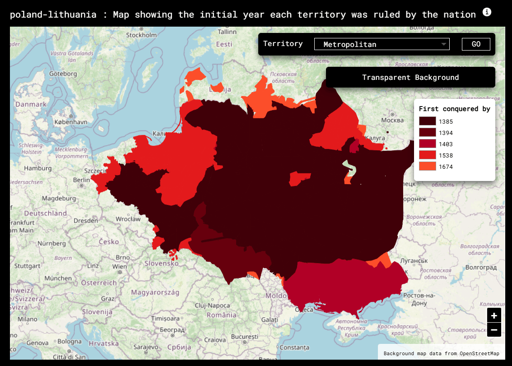

The case of Armenia stands out for its historical depth and the multiplicity of its state incarnations. From the ancient Kingdom of Urartu (860–585 BCE) to its reincarnations as the Kingdom of Armenia (321 BCE–428 CE) and the curious “exiled polity” represented by the Kingdom of Armenian Cilicia (1078–1375), the territory has continuously passed under Persian, Seleucid, Roman, Arab, Byzantine, and Ottoman dominations. At the height of its territorial expansion, in 77 BCE, ancient Armenia appeared as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Territorial projection of the Kingdom of Armenia at its zenith in 77 BCE, illustrating the spatial foundation upon which later claims to sovereignty and identity would be constructed.

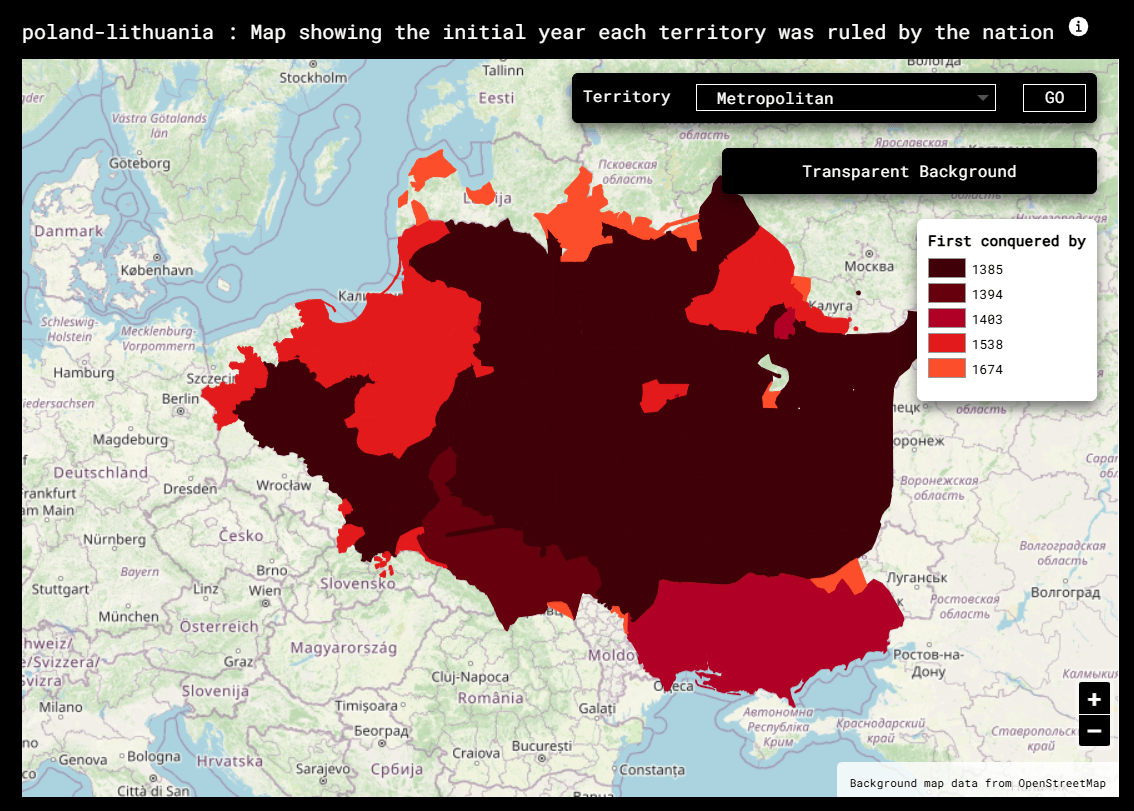

Armenia subsequently experienced a condition of intermittent sovereignty, in which statehood alternated with long periods of foreign subordination. This process is clearly illustrated in a graph depicting the area of ancient Armenia, where the periods of subjection to other entities are distinctly visible (Figure 2). Despite territorial fragmentation and the absence of a unified state for centuries, Armenian identity remained alive through its language and Christian religion (adopted as the state faith as early as 301 CE).

Contested for centuries by Romans, Parthians, Byzantines, and Arabs, Armenia was reborn as a kingdom in 886 thanks to the intervention of King Ashot (890 AD). On that foundation, the Armenian people would later develop further aspirations for unity, though they were subsequently subdued by the Seljuks (1045–1200), the Mongol Ilkhanate (1236–1335), the Ottoman Empire (1514–1828), and then the Russian Empire (1828–1917). The founding of the Republic of Armenia in 1918 and its rebirth in 1991, following the final collapse of the Soviet Union, represent moments of sovereign reactivation, in which latent statehood was transformed into a recognized political entity.

Figure 2. Temporal graph of Armenia’s fluctuating sovereignty, highlighting the alternation between autonomous rule and foreign domination. The dataset reflects both ancient and modern clusters, underscoring the longue durée of Armenian statehood.

More than other cases, Armenia demonstrates that statehood is not a continuum, but rather an oscillation between presence and absence and between power exercised and power imagined. Moreover, the Armenian people share the traumatic experiences of diaspora and genocide with the Jewish people (perpetrated by the Turks between 1915 and 1923)—elements that, paradoxically, seem to catalyze unifying ambitions and reinforce the desire to restore an Oikos for their Ethnos. (Oikos in Ancient Greek refers to the fundamental domestic unit, encompassing the family, property, and internal economic relations; Ethnos instead designates a human group united by language, culture, and traditions, often in contrast to external groups.)

Vietnam—A Suspended State Through the Millennia

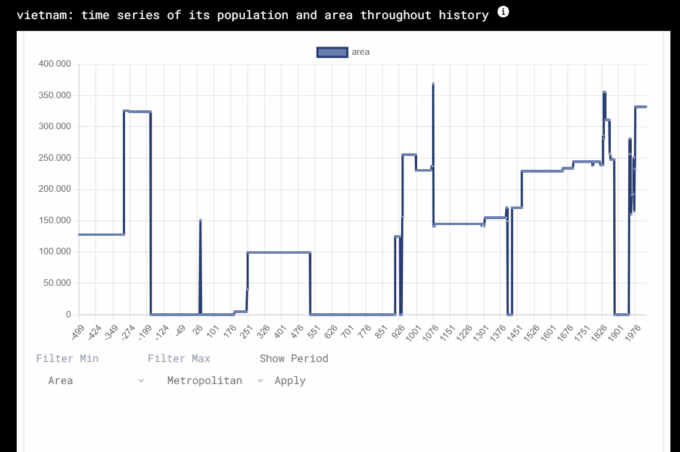

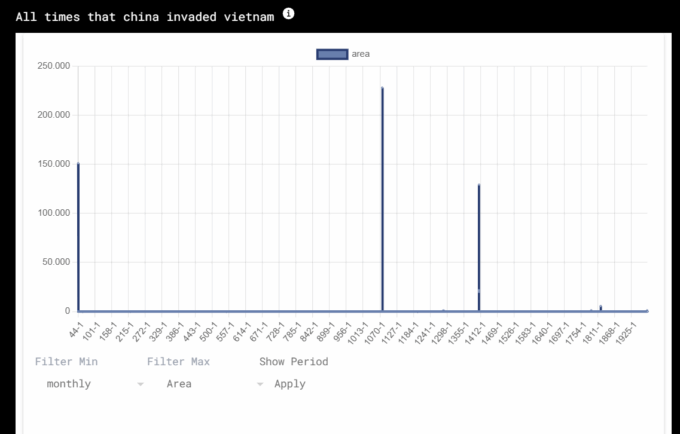

The history of Vietnam is marked by a recurring alternation between moments of sovereignty and phases of subjugation. This is clearly visible in the graph in Figure 3, where—compared to the previous Armenian case—one can appreciate the great variability and frequency with which the Vietnamese state has undergone foreign occupations. It is all the more interesting, therefore, to compare this graph with the one depicting the times China has invaded Vietnam throughout history (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Chronological visualization of Vietnam’s intermittent sovereignty, revealing the cyclical nature of its political autonomy and the frequency of external subjugation across two millennia.

Figure 4. Historical mapping of Chinese incursions into Vietnam, disaggregated by dynastic clusters. The graph emphasizes the persistent geopolitical tension and the role of invasion in shaping Vietnamese state formation.

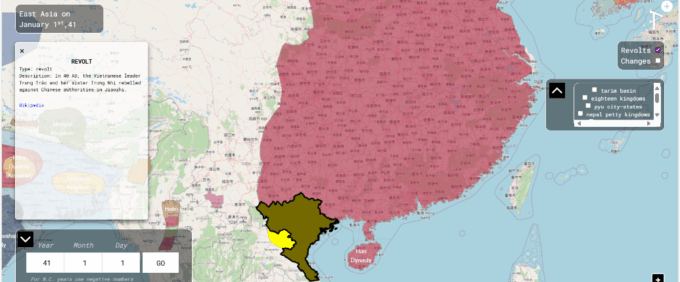

The emergence of the kingdom of Nam Việt as early as 207 BCE represented the first form of autonomy. But this was soon interrupted by the first Chinese domination, which inaugurated a long series of imperial subjugations starting in 111 BCE. Brief interludes of rebellion, such as that of the Trưng sisters (Figure 5), occurred within a continuum of successive dominations: the second (43–544), the third (602–905), and the fourth (1407–1427), interspersed with episodes of ephemeral or partial independence. True independence was consolidated in 938 with Ngô Quyền’s victory on the Bạch Đằng River, marking the beginning of a period of sovereignty that withstood even the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Figure 5. Geospatial reconstruction of the Trưng sisters’ uprising (40–43 CE), offering insight into early female-led resistance and the territorial scope of proto-national mobilization against imperial rule.

However, from the 16th to the 19th century, Vietnam entered a phase of internal fragmentation, marked by the coexistence of rival dynasties and increasing geopolitical vulnerability. The French domination (1887–1953) marked a renewed loss of sovereignty, further aggravated by the brief Japanese occupation in 1945. Only through the long war of independence (1955–1975), culminating in postwar reunification, did Vietnam regain full statehood, reactivating a sovereignty that, although more recent, is rooted in a long memory of resistance and resurgence. Particularly interesting, relating to the centuries-long history of the Vietnamese state, is the ranking of major geopolitical changes triggered in a wartime context (Figure 6). Figure 6 is especially relevant as it illustrates how war, despite its destructiveness, often acts as a catalyst for territorial redefinition and the resurgence of Vietnamese sovereignty. Each conflict marked in the chart represents not only a crisis but also an opportunity for the consolidation of national identity and the reaffirmation of statehood.

Figure 6. Comparative ranking of major conflicts affecting Vietnam’s territorial integrity, illustrating how warfare has historically functioned as a vector of both fragmentation and sovereign consolidation.

Poland—The Quintessential Revived State

Poland represents one of the most emblematic examples of a revived state in the modern era. Following the three partitions of the 18th century (1772, 1793, and 1795), the country formally disappeared from the European map for more than a century, having been absorbed by the Russian Empire, Prussia, and Austria. Nevertheless, the cultural, linguistic, and religious continuity of the Polish population—combined with the persistence of insurrectionary movements and national literary and historical production—kept alive the idea of suspended sovereignty.

In this sense, 19th-century Poland can be interpreted as a latent state, lacking legal recognition but active in the symbolic and identity spheres. The restoration of statehood in 1918, at the end of World War I, marked the return of effective sovereignty, which would again be challenged during World War II and the Soviet era. Poland thus embodies a cyclical nature of statehood, where legal death does not equate to political extinction, and where the reemergence of the state is the result of a long cultural and geopolitical gestation.

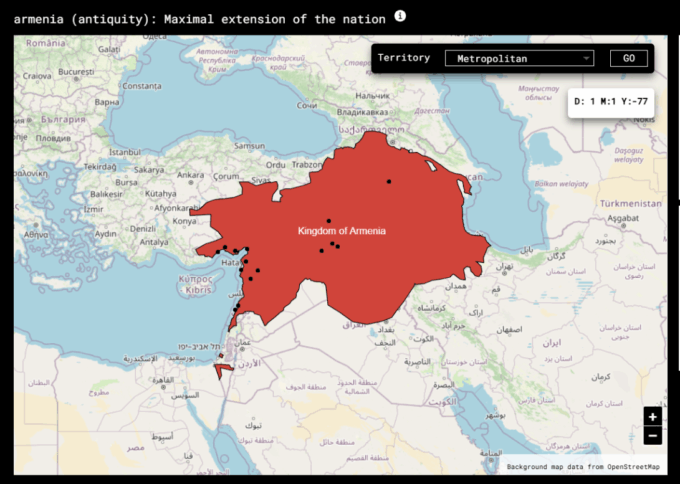

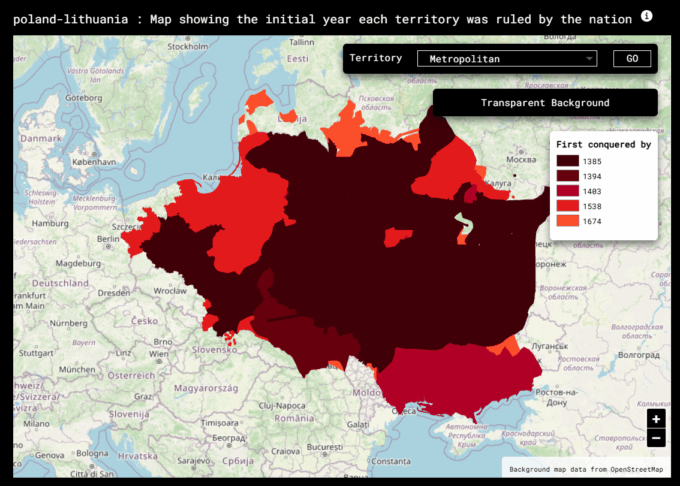

Figure 7. Cartographic chronology of territorial integration within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, tracing the expansion of a composite sovereignty across Central and Eastern Europe.

The history of Poland is a succession of assertions of sovereignty and dramatic interruptions. Beginning in 966 with the Christianization of the duchy, the first political identity took shape and was consolidated in the Kingdom of Poland (1026–1385). This personal union with Lithuania marked the start of a phase of expansion and prestige, culminating in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of 1569—one of the largest political entities in early modern Europe (Figure 7). However, between the 18th and 19th centuries, Poland underwent three partitions (Figure 8), which erased its statehood for more than a century.

Figure 8. Post-partition map of Central Europe (1796), depicting the geopolitical erasure of Poland and the redistribution of its territory among imperial powers—a visual testament to the fragility of state borders.

[Content truncated due to length…]

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed