Claudio Abbado was conducting Mussorgsky right next to the Dave Brubeck Quintet. The collision made crazy, coincidental sense, a compelling mash-up: Taking Five on Bald Mountain.

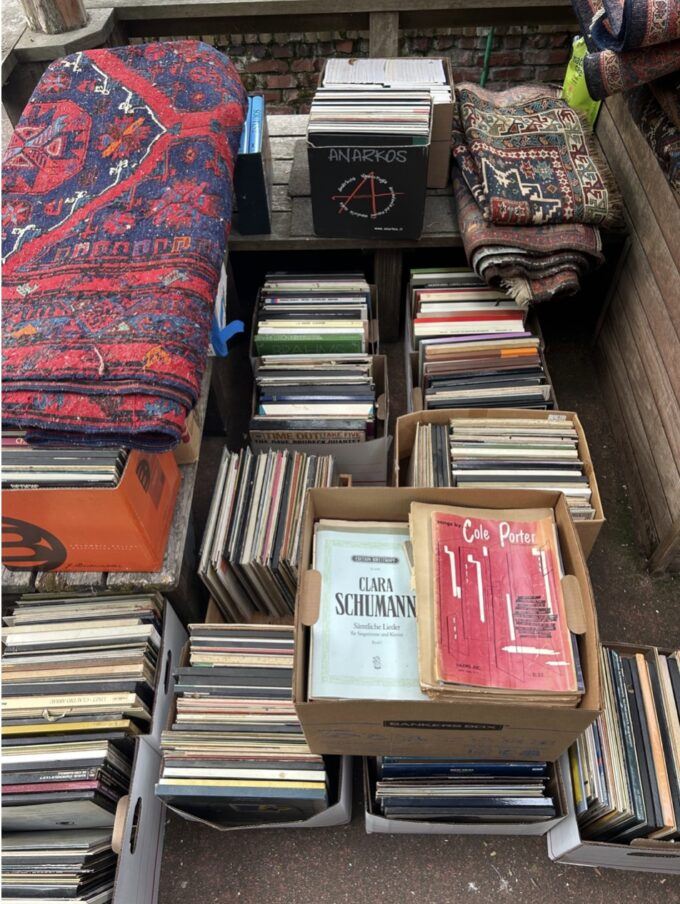

Nearby, Elly Ameling sang Bach while leaning on a box set from another Claudio—Arrau, the late Chilean pianist—doing lots of Liszt.

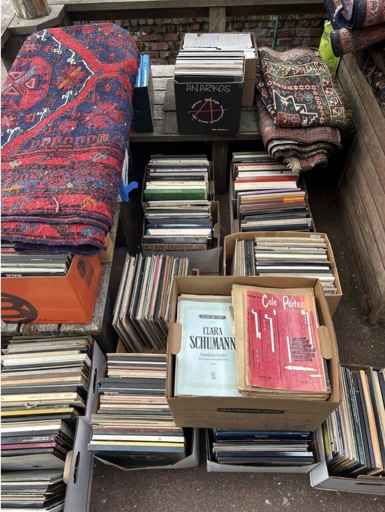

We’d been removing our old professor’s LPs from their shelves and putting them into cardboard boxes and bringing them upstairs to the entryway porch for the collectors to pick over. Along the way, the discs had been de-alphabetized, the genres jumbled: B next to L; Viennese symphonists consorting with Parisian cabaretists; operas in with organ music; Randy Newman and the Beatles mingling with Massenet and Mozart.

I put down another forty-pound box of LPs and regarded the Abbado album cover. Here was a conductor’s cult I’d be willing to join in a baton beat. The photograph showed the Leftie Maestro at work at the Mussorgsky recording session. His baton was raised nearly to the perpendicular just above the top of his head, his elbow cocked. His left hand was fully extended, his index finger pointing towards the back row of the unseen orchestra that he looked intensely out at. Abbado must have been captured cueing the percussion section, likely the cymbals that are so crucial to the frightful fun of that Night on Bald Mountain. As always, Abbado was working without a score. His was a beautiful musical mind.

Under his raised left arm, a big dark stain of sweat darkened his light blue shirt. Many a vain conductor wouldn’t have allowed such an image to be published, but Abbado sweated profusely and proudly. Conducting was work, though he would have been the first to admit that the podium wasn’t the kind of sweatshop he fought against in co-founding the Music Against Child Labor Initiative with the International Labor Organization. If Abbado had been here to help us schlepp vinyl he would have kept those blue shirtsleeves rolled up, dropped his baton, and grabbed some boxes.

As I flicked through the LPs, other conductors, some long since cancelled, flashed past. A big-haired James Levine smiled a welcome to his interpretation of all four Schumann symphonies, recorded a half-century before his fall from power for propositioning teenage boys at the Metropolitan Opera. His shirt was open at the top to reveal a hairy chest and his dreamy blue eyes sent a very different message in retrospect of his depredations.

The Schumann record had sat at the end of the shelf and its decades in that position had allowed the unrelenting California sunlight to bleach a perfectly straight stripe along the left edge of the cover—not a scarlet letter but a louche band of blue, as if Nature were intent on revealing Levine’s crimes.

Now Levine and his Schumann symphonies were in the dappled shadow on the porch along with a thousand other LPs. By my calculation, that was about half of the massive collection that had been amassed by our professor friend. The house had to be emptied so the real estate agent could come in and stage the place. LPs and the thousands of books—a large proportion of them about music—had to go, and soon. The thousands of CDS had already been sold for next to nothing to a dealer. The LPs were harder to find a home for. The Friends of the Library sale wasn’t taking any more vinyl. Salvation Army didn’t want them either.

Halfway through the morning, we went to get coffee and saw a sticker on the side of a newspaper vending machine: “Will Buy LPs.” We called the number and the guy came round that afternoon while we were at the recycling center with bags full of musicology journals. The prof let the LP-“buyer” pick out a couple of Poulenc records for his private collection and leave the rest. The next morning, another vinyl ragpicker called and said that he might come by to have a look at the boxes in a few days. We rented a 10-foot U-Haul truck to transport much of the furniture to an auction house, but it didn’t want the records either.

Our friend had a storage unit that was already filling up. He didn’t seem too concerned about the fate— not to mention the weight—of the LPs.

From where I was standing and sweating—not with the style of Abbado, but a growing sense of dread at the disposal of the sheer tonnage of so many once-valued and valuable things—it all looked bleak. A vinyl record revival was underway in the USA and across the world, yet it wasn’t booming on our friend’s doorstep. More than 50 million vinyl LPs were sold in 2024, yet our friend’s collection had one foot on a banana peel and the other in the county dump.

Kyle Devine’s fascinating and unsettling 2019 book, Decomposed: the Political Ecology of Music, lays bare the environmental costs that accrue not only from production and distribution, but also from the disposal of these plastic marvels.

Across the centuries and into our time, many great collections—of art, musical instruments, books—have been dispersed on the death of the collector. One shouldn’t get too sentimental about these centrifugal forces. Still, the image of us tipping all of our friends LPs into a dumpster filled me with melancholy.

I looked into one of the boxes and was surprised to spot a Pharaoh Sanders album. Not just the ancient Egyptians, but many other cultures, have buried their dead with their belongings: as well as food, oil and wine, clothes, art and idols to uplift and protect them on their posthumous journey and sustain them in the afterlife.

What about building cryogenic storage in which the deceased can be surrounded by their books and records, the unit equipped with a turntable, lamp and armchair. In these upscale mini-mausoleums, robotic arms of the Eternal Attendant could pluck the LPs from their sleeves and set them in place, then drop the needle. Speakers could play the music aloud, or headphones could be put on the dearly departed’s head. It takes about 60 days to listen to 2,000 records. Those coming to pay their respects could, if bundled up, enter the cold chamber, or stay outside and listen along with the loved one with headphones placed next to the viewing window. The electricity for all this could come from eternally sustainable sources, the cost paid for by provisions in the will.

The younger generation will mostly prefer to have their consciousnesses uploaded into the cloud to co-mingle with their Spotify playlists and be visited by both the living and the dead.

But surely there are millions of vinyl aficionados, both new and old, eager to set up cryo-crypts where their collections play on in perpetuity—or at least until the trumpet sounds on the Last Day.

More than a few Prophets believe that the Apocalyptic blast will also be heard in stereo and on vinyl.

The post Vinyl Afterlives appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed