Photo: Michael Nigro/Sipa/AP

Photo: Michael Nigro/Sipa/AP

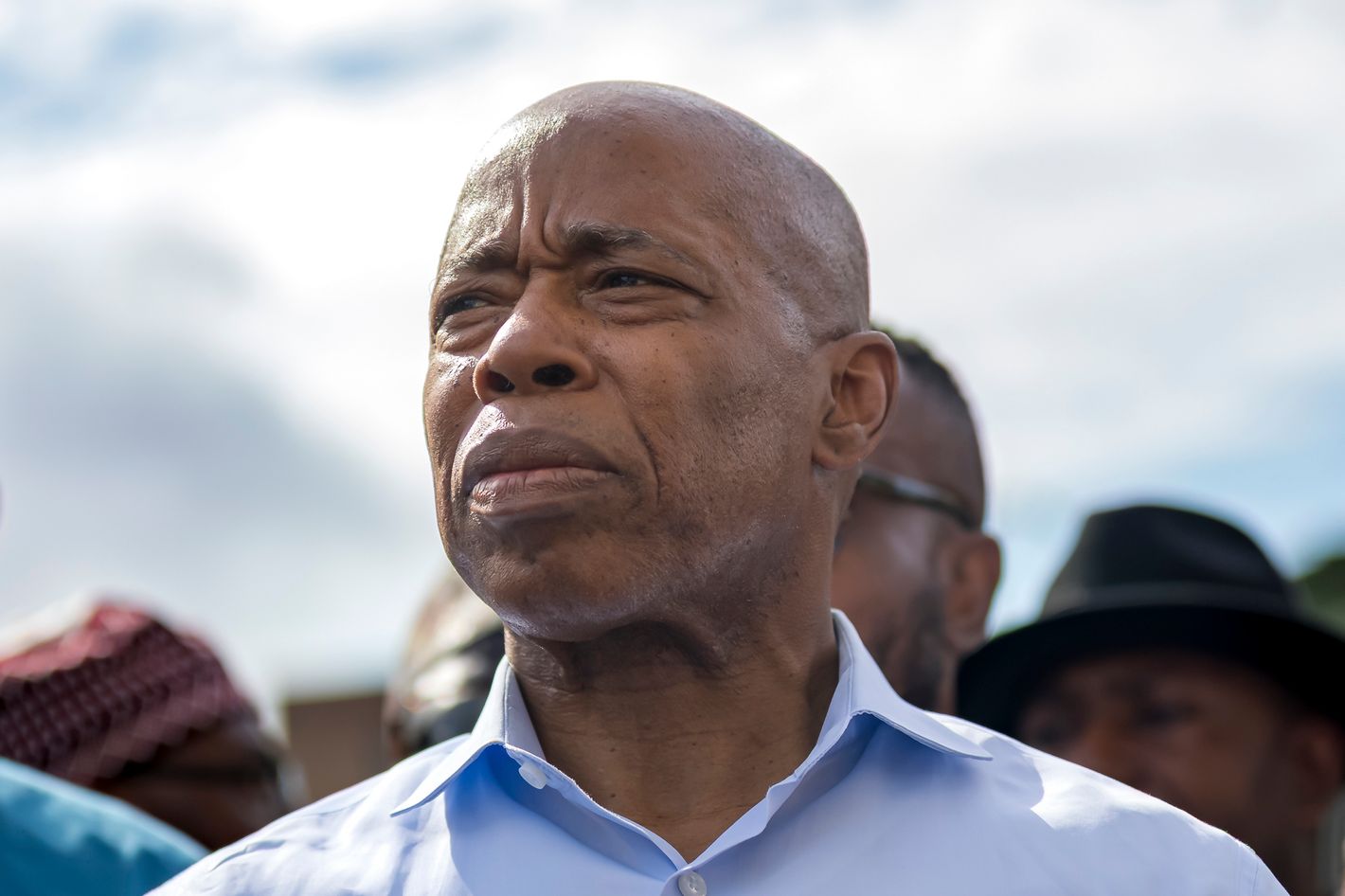

As the curtain goes up on the post–Labor Day push to Election Day, Mayor Adams, tanking in the polls, is making unsubtle tribal appeals to the Black communities that powered him to victory four years ago, frequently reminding voters that he is second Black mayor in city history after David Dinkins.

But political leaders in vote-rich Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and Southeast Queens neighborhoods are increasingly connecting with Zohran Mamdani or Andrew Cuomo, and polls suggest that voters are doing the same.

The mayor’s collapse in support is not new. Back in January — before Cuomo entered the race and well before Mamdani’s surge, at a time when Adams was facing federal corruption charges — one survey found that only 6 percent of Black voters said the mayor should run for reelection, compared with an eye-popping 78 percent that said he should quit.

“All these Negroes who were asking me to step down, God, forgive them,” Adams said from the podium at Gracie Mansion during a Black History Month event in February, mocking his critics. “Are you stupid? I’m running my race right now.”

Black voters aren’t stupid, but the word I keep hearing from many of them, especially older New Yorkers, is embarrassed. People in my neighborhood find it embarrassing that the city’s second Black mayor was arrested and indicted on federal charges of scamming luxury travel and other undisclosed gifts from business donors, only narrowly escaping a criminal trial after the Trump administration intervened. And nobody was happy about the humiliating spectacle of Trump’s blustering border czar, Tom Homan, crudely threatening Adams on national television, warning that if the mayor failed to cooperate with ICE’s mass-deportation campaign, “I’ll be back in New York City and we won’t be sitting on the couch. I’ll be in his office, up his butt saying, ‘Where the hell is the agreement we came to?’”

Not all of Adams’s political problems stem from his legal ordeal. Prominent activists say the mayor has fumbled key issues of importance to Black communities. One lost opportunity is City Hall’s refusal to comply with a legal requirement to issue a report every two years on how to close racial gaps in New York around hiring, promotion, home ownership, education, and other quality-of-life measures. After more than 500 days of delay, the city’s Independent Commission on Racial Equity has sued the mayor for the still-unreleased plan.

“It’s mind-boggling. This is something that the voters said that they wanted to happen,” City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said. “And now we have an administration that is saying, ‘No, we’re not going to do this,’ or ‘Yeah, we’ve got it, but we’re not going to show it to you.’ That is not acceptable.”

Adams has also drawn criticism over the deep fiscal cuts he made to CUNY over the past four years in a city where racial disparities in higher educational are stark. According to a report by the Center for an Urban Future, 64 percent of working-age white New Yorkers have a college degree, compared with only 27 percent of Blacks and just under 20 percent of Latinos. Adams cut the CUNY budget by $126 million over the first three years of his administration. Only in this Election Year did the money get restored, but lasting damage was done: The city’s community colleges have lost an estimated 400 faculty members. “It’s disappointing that it took three years for this administration to become tired of being entirely on the wrong side of doing right by New Yorkers,” Speaker Adams said in a statement.

On the hot-button issue of public safety in Black neighborhoods, Adams has been criticized on multiple fronts. Police stops have increased every year of his tenure — up by more than 50 percent last year — with Black and Latino New Yorkers making up nine out of every ten stops. The federal monitor overseeing the NYPD’s stop and frisk policies found that just under a third of searches and frisks in early 2024 were unconstitutional and that officers failed to report four-in-ten stops in 2024.

Mayor Adams has also been soft on officer misconduct, forcing out the chair of the NYPD’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, Arva Rice, the CEO of the New York Urban League, after she raised objections to the way police officials stonewalled and covered up information about the killing of Kawaski Trawick, an unarmed man shot to death in his home by a white officer in 2019. The CCRB remains without a permanent chair.

So Black voters have ample cause to look elsewhere, and Adams’s shortcomings have left a vacuum that his political rivals are rushing to fill. Ever since Mamdani shocked the political Establishment with a come-from-behind win in June and Cuomo retooled his campaign to make a general-election run as an independent, Black power brokers who supported Adams in 2021 have been looking elsewhere, and many of them are connecting with Mamdani through Patrick Gaspard, who served as White House political director under President Obama and has been an informal adviser to Mamdani.

Attorney General Letitia James, Speaker Adrienne Adams, State Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, and Public Advocate Jumaane Williams are all with Mamdani, as are Borough Presidents Vanessa Gibson of the Bronx and Donovan Richards of Queens, along with leaders of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Democratic organizations. By comparison, Adams has been backed by few prominent leaders besides ex-governor David Paterson.

I asked the Brooklyn chair, Assemblywoman Rodneyse Bichotte Hermelyn, if she had even considered backing Adams, a fellow Brooklynite whom she’d supported in 2021. “No, I did not,” she told me. “My consideration was for only the people who were running in the Democratic primary. So he knows that I’m not going to be supporting him, that I have already endorsed the Democratic nominee.”

It’s not clear whether Cuomo will draw the same large share of Black votes he got in the primary. Sharpton called on Cuomo to drop out of the race, but the ex-governor is charging ahead and will likely get a share of older Black voters who supported him and his father, the late governor Mario Cuomo, over the years. That leaves a shrinking share of the Black base for Adams, whose supporters are leaning hard on ethnic solidarity.

“When he got to City Hall, history repeated itself — and the system tried to tear down another Black mayor,” says the ominous narrator of an online ad ginned up by Empower NYC, a pro-Adams political-action committee. A flyer by the same group shows photos of Adams and Dinkins and says “30 years ago they were successful in derailing New York’s first Black mayor and now they are trying to do the same with Mayor Eric Adams.”

The comparison is wildly inaccurate. Dinkins, a solid family man and lifelong Democrat, surrounded himself with qualified government managers and ran an administration that was overwhelmed at times but free of corruption. Adams, who has seen top aides arrested and charged, has veered from glib boasting (“When does the hard part start?”) to conspiratorial suggestions that “they” are trying to stop him because he’s Black. We will soon see whether Black voters buy that or whether the trickle of voters away from Adams will turn into a flood.

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed