The storm had passed, but the water kept rising. In September 2017, Hurricane Irma slammed into Florida, causing tides to surge and dumping about a foot of water across much of the state. A few days later, Jane Blais stood on a bridge with her neighbors near her High Springs ranch, watching the Santa Fe River below swell higher and higher.

“We had zero notice,” Blais said, recalling how she ran home to evacuate the tenants of a small cluster of apartments she owned and move her horses to higher ground. “It came in so fast, completely abnormal.”

By the end of the day, Blais’ rental units were soaking in 3 feet of floodwater, and her horses — despite her best efforts — were submerged chest-deep. Her darkest moment came when veterinarians at a nearby university warned that her horses might die. As the water rose and the hours dragged on, she considered shooting them to spare them from drowning or disease. Around her, neighbors reported destroyed homes, lost belongings, and an unrecognizable landscape.

State officials arrive at Jane Blais’ flooded property during Hurricane Irma in 2017. Capt. Martin Redmond / Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

State officials arrive at Jane Blais’ flooded property during Hurricane Irma in 2017. Capt. Martin Redmond / Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Such scenes are not uncommon with powerful storms, which are moving more slowly and holding more water as the planet warms. Last year, Hurricane Helene’s deluge buckled river banks and mountainsides in North Carolina, and this summer, heavy rain in Central Texas flooded the Guadalupe River, claiming at least 138 lives.

But eight years later, Blais and others still believe Hurricane Irma shouldn’t have affected them: Residents of inland, rural counties that rarely flood, even during hurricanes with heavy rainfall. Their perspective aligns with flood risk analyses from First Street, a nonprofit that assesses climate risk, which has rated the flood risk in the county where Blais lives as “minor,” with a risk value slightly lower than both the state and national average. According to National Water Prediction Service records, river level gauges near Blais’ home measured a record high a few days after Hurricane Irma.

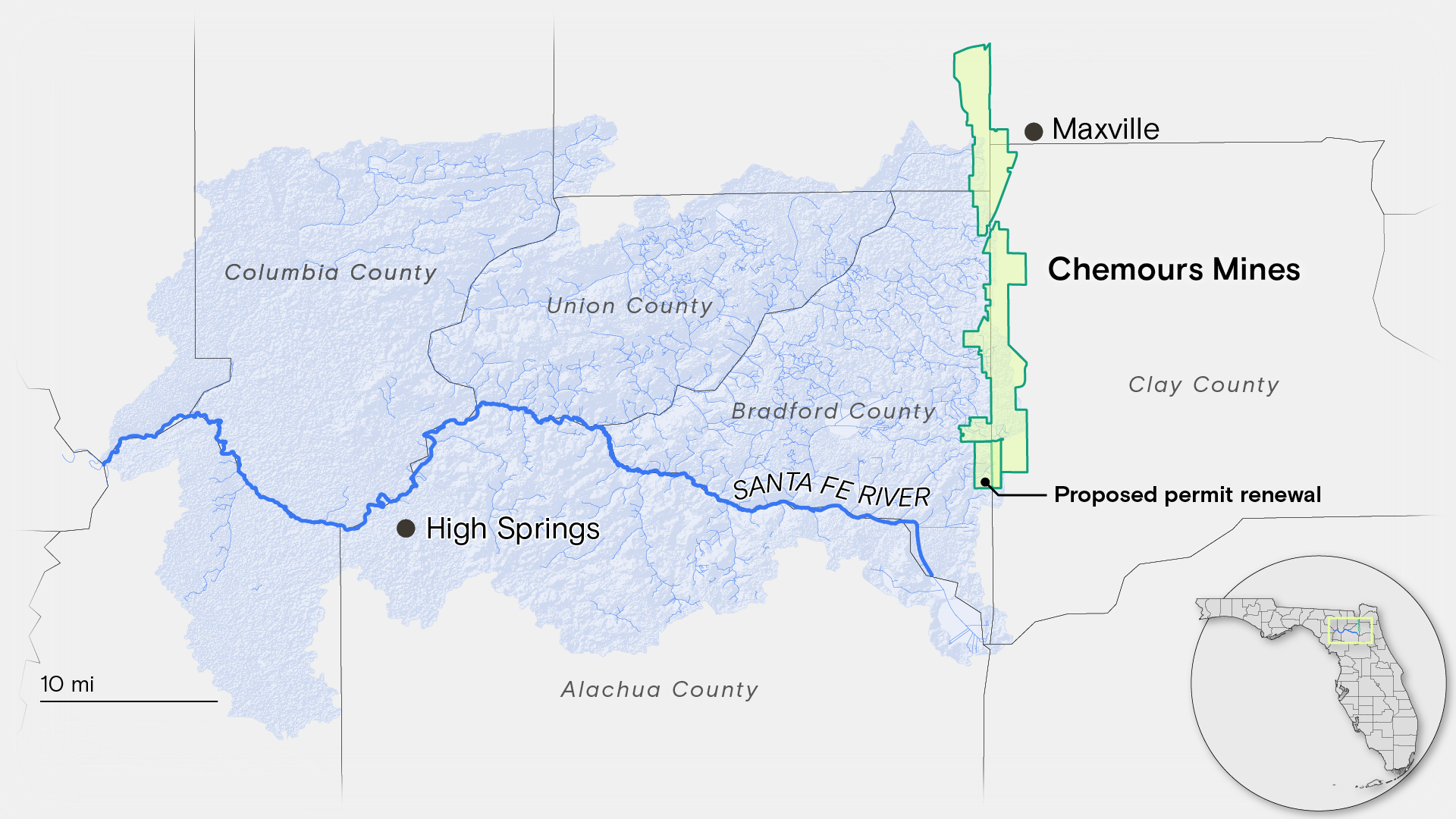

Instead, they suspect another culprit: the Chemours mining complex, which sprawls across three counties some 50 miles upstream. The company released over 350 million gallons of wastewater near the headwaters of the Santa Fe River over the course of a week after Hurricane Irma made landfall. At one point, the flow peaked at nearly 80 million gallons per day — double the company’s permitted allowance. Those living next to the mine also fear its routine releases are causing their towns to regularly flood with low levels of contaminated water.

Sources: Florida Department of Environmental Protection, USGS.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

Sources: Florida Department of Environmental Protection, USGS.

Jesse Nichols / Grist

Chemours’ mining operations in Florida trace back to 1949 and were originally run by DuPont, a chemical company that Chemours spun off from a decade ago, in part to protect itself from PFAS-related liabilities. The company is now one of the largest producers of titanium dioxide in the world, which it makes with the mineral ores mined in Florida. The compound is used in a wide range of products, from the laminate coatings on furniture and home appliances to the vibrant coloring on popular candies and toothpaste.

Chemours has permits from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the state agency that oversees environmental regulation, to release a total of more than 40 million gallons of treated wastewater per day from three mines and two processing sites in the area — a relatively standard amount of effluent for mines in the U.S. to release. During emergencies, like Hurricane Irma, the company has been allowed to exceed this limit.

In addition to flooding, residents are concerned about the exposure to the radium that is unearthed by the mining process. State records show that tests of Chemour’s wastewater contain radium levels that regularly exceed federal limits, with the most recent violation reported in 2023. This year, Chemours applied for a fresh permit to continue operating a mine in Bradford and Clay County, a move that would discharge wastewater into the headwaters of the Santa Fe River for another 10 years.

In a written statement, C.J. Hilton, vice president of mining operations at Chemours, told Grist that the flooding that followed Hurricane Irma was the result of a 100-year rain event that caused flooding across the state, and isolating the responsibility of any one facility for the flooding would require a basin-scale hydrologic study. “It would not be accurate to say that Chemours is responsible for the flooding,” he said. “Chemours takes environmental deviations and permit compliance extremely seriously.”

The company has set up a community advisory panel and works with regional officials to reduce water flows during peak conditions, he said. “To our knowledge, we have not heard any feedback, either directly from our [advisory panel] members or the broader community, regarding flooding surrounding our mines in recent years,” he added. “When we do receive feedback from our community members, we always try our best to address their concerns.”

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection, or FDEP, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. As of the time of this story’s publication, a public records request filed by Grist in early May has not been fulfilled, nor have repeated inquiries sent to the FDEP Office of the Ombudsman and Public Services concerning the status of the request been addressed.

To be sure, just because an area has a low risk of flooding doesn’t mean that it never will, and linking health problems to pollution is notoriously difficult. Complicating matters, the list of environmental hazards near the mines is long and includes a former superfund site, a PFAS-contaminated military camp, a decommissioned nuclear storage site, and runoff from toxic coal ash, which was used to pave roads in a neighboring county.

Increasingly erratic rainfall patterns and storms are fueling severe, chronic flooding in rural parts across the country, including regions unaccustomed to such floods and often ill-equipped to manage the resulting damage. Limited resources and a fertile online ecosystem have allowed for the proliferation of misinformation in the aftermath. After the flash floods in Central Texas, false claims that cloud seeding was to blame spread online. And following Hurricane Helene last year, claims that the government was responsible for the storm hindered emergency responders.

Those who live near Chemours and downstream of its mining operations feel similarly neglected. Local officials haven’t formally surveyed any of the community’s flooding or health claims. Instead, a group of residents across several counties has taken the investigation upon themselves — sampling creeks, petitioning waterboards, consulting with scientists, and monitoring Chemours’ public records. They say their concerns aren’t taken seriously by officials. Without support from authorities or data to back up their claims, these residents say they feel abandoned, left to connect the dots themselves, and desperate for answers.

“You would have had to experience it, because everybody just thinks you’re a conspiracy theorist and you’re nuts, and I’m not at all a conspiracy theorist,” Blais said. “By the time we actually find out how badly [Chemours has] ruined the river and the wetlands around them… It’s going to be bad.”

Jane Blais stands with her horse that she relocated after a 2012 flood.

Brad McClenny / USA TODAY NETWORK via Imagn Images

Jane Blais stands with her horse that she relocated after a 2012 flood.

Brad McClenny / USA TODAY NETWORK via Imagn Images

AA little over a year before Hurricane Irma made landfall, clean water and environmental health advocates had banded together to protest proposed phosphate mines in nearby Bradford and Union County. In the process, they formed Citizens Against Phosphate Mining, a small community action group. In addition to their primary, anti-phosphate mission, they began keeping an eye on Chemours.

When Blais’ property flooded in 2017, a group member advised she get in touch with Sydney Bacchus, a wetlands hydroecologist. Among the activists, Bacchus is known for her long history of advocating against mining, which she says stretches back to her time working as a scientific expert for the state’s environmental regulatory agency, analyzing the industry’s impact on wetlands.

Prompted by Blais’ story, Bacchus and another member of the advocacy group drove around the state collecting photos and measurements of areas flooded after Hurricane Irma. Eventually, in 2019, Bacchus and several colleagues published a peer-reviewed paper that combined their findings with data from the U.S. Geological Survey on historical water heights. The paper concluded that wastewater discharge from Chemours was a contributor to the Santa Fe River floods.

Chemours’ wastewater discharge was “contributing to the increasing severity and duration of flooding” in the Santa Fe River basin, Bacchus and her co-authors concluded.

The paper was published in the Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, a controversy-ridden open-source publication. The journal is run by Scientific Research Publishing, which appears on Beall’s List, a watchdog index that flags journals that charge high publication fees, offer minimal or nonexistent peer review, or publish papers with little scientific merit.

Bacchus’ paper did not prompt any action from Chemours, local governments, or the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which is responsible for regulating mining in the state. But to the activists, Bacchus, who has a doctoral degree, became one of the few qualified experts who listened to the community’s concerns. And after two decades spent working with environmental advocates on mining issues in the region, she’d earned their trust. For the activists, the paper represented a turning point, becoming a key part of their growing outrage over Chemours’ practices.

According to a review of publicly available Florida Department of Environmental Protection documents, Chemours facilities have reported at least 16 emergency wastewater incidents since 2017. In the last three years, at least four of these resulted in the release of hundreds of thousands of excess gallons of water. Most of these overflows went into nearby wetlands after breaching the mine’s berms, which are retaining walls made of piled sediment or concrete.

The largest emergency release, reported on December 26, 2022, was reported as over 510,000 gallons — enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Others are more modest, such as 1,200 gallons released in September of last year. This past February, an incident resulted in the spill of 230,000 gallons. (Hilton, the Chemours official, attributed the December 2022 release to a freeze that caused power outages and industrial upsets across the South.)

TA little over a year before Hurricane Irma made landfall, clean water and environmental health advocates had banded together to protest proposed phosphate mines in nearby Bradford and Union County. In the process, they formed Citizens Against Phosphate Mining, a small community action group. In addition to their primary, anti-phosphate mission, they began keeping an eye on Chemours.

When Blais’ property flooded in 2017, a group member advised she get in touch with Sydney Bacchus, a wetlands hydroecologist. Among the activists, Bacchus is known for her long history of advocating against mining, which she says stretches back to her time working as a scientific expert for the state’s environmental regulatory agency, analyzing the industry’s impact on wetlands.

Prompted by Blais’ story, Bacchus and another member of the advocacy group drove around the state collecting photos and measurements of areas flooded after Hurricane Irma. Eventually, in 2019, Bacchus and several colleagues published a peer-reviewed paper that combined their findings with data from the U.S. Geological Survey on historical water heights. The paper concluded that wastewater discharge from Chemours was a contributor to the Santa Fe River floods.

Chemours’ wastewater discharge was “contributing to the increasing severity and duration of flooding” in the Santa Fe River basin, Bacchus and her co-authors concluded.

The paper was published in the Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, a controversy-ridden open-source publication. The journal is run by Scientific Research Publishing, which appears on Beall’s List, a watchdog index that flags journals that charge high publication fees, offer minimal or nonexistent peer review, or publish papers with little scientific merit.

Bacchus’ paper did not prompt any action from Chemours, local governments, or the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which is responsible for regulating mining in the state. But to the activists, Bacchus, who has a doctoral degree, became one of the few qualified experts who listened to the community’s concerns. And after two decades spent working with environmental advocates on mining issues in the region, she’d earned their trust. For the activists, the paper represented a turning point, becoming a key part of their growing outrage over Chemours’ practices.

According to a review of publicly available Florida Department of Environmental Protection documents, Chemours facilities have reported at least 16 emergency wastewater incidents since 2017. In the last three years, at least four of these resulted in the release of hundreds of thousands of excess gallons of water. Most of these overflows went into nearby wetlands after breaching the mine’s berms, which are retaining walls made of piled sediment or concrete.

The largest emergency release, reported on December 26, 2022, was reported as over 510,000 gallons — enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Others are more modest, such as 1,200 gallons released in September of last year. This past February, an incident resulted in the spill of 230,000 gallons. (Hilton, the Chemours official, attributed the December 2022 release to a freeze that caused power outages and industrial upsets across the South.)

The volume of water that causes a flood depends on a number of factors, including the region’s topography. In 2015, just 3 million gallons of toxic wastewater accidentally released by an Environmental Protection Agency clean-up crew at a mine in Colorado were enough to wreak havoc across a waterway winding throughout the Navajo Nation and three states. Across flat land, roughly 330,000 gallons is sufficient to flood an acre with one foot of water.

So, where does all the wastewater from Chemours end up? It’s a question that has plagued the activists. The company’s official discharge sites send the water — as permitted — through natural watersheds that feed a local lake and several rivers, including the Santa Fe. But in a wetland shaped by heavy rains and booming housing developments that can block natural drainage, it’s difficult to track where water goes or pin down a source of flooding.

Floodwater from Florida’s Santa Fe River submerges a house in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma in 2017. Tim Donovan / Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Floodwater from Florida’s Santa Fe River submerges a house in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma in 2017. Tim Donovan / Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Some residents, like Christy Carter, believe Chemours is responsible for the water swamping nearby neighborhoods, covering sidewalks, and filling drainage ditches. In her hometown of Maxville, which abuts much of Chemours’ operations in Clay and Baker counties, she says the community playground sits in inches of water nearly year-round.

Carter is also worried about the local radium contamination. She believes the company’s activities are behind some of the town’s most severe health problems, including serious cancer cases in her immediate family. Clay County has a higher incidence rate of cancer than the national average and the 10th highest rate in the state of Florida. There has been no government study of mining impacts on health in Maxville or other nearby towns.

Carter has tried to generate local interest around the mine’s impacts. She co-runs “Save Maxville,” a local Facebook group dedicated to concerns about overdevelopment and pollution in the community. In addition to a handful of other anti-mining activists in the nearby counties, residents have written op-eds in the local paper, voicing concerns about wastewater spilling from Chemours’ facilities.

“People around here will tell you, I’m dying, but hey, they’ve been doing it forever. So what can you do?” she said. “I mean, you can’t throw a rock and not hit somebody that has cancer or some kind of debilitating autoimmune disease.”

Christy Carter lives near a Chemours mine in Clay County, Florida, and runs a Facebook group dedicated to concerns about overdevelopment and pollution in the community.

Sachi Mulkey / Grist

Christy Carter lives near a Chemours mine in Clay County, Florida, and runs a Facebook group dedicated to concerns about overdevelopment and pollution in the community.

Sachi Mulkey / Grist

Radium contamination often builds up near titanium mines, as titanium-bearing ores naturally occur alongside other heavy minerals, including radioactive elements. These elements decay into radium, which can become concentrated in the mining waste byproduct after the titanium-bearing ore has been extracted.

According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s testing records, Chemours’ wastewater has been contaminated with radium for at least 29 years. Although there is no known safe exposure level, and contamination in Chemours’ water fluctuates, its levels of radium-226 and radium-228 have often exceeded the 5.0 picocuries per liter limit set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

In June 1996, Chemour’s radium contamination was found to be nearly three times greater than this limit. The following year, Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection placed the company under a consent order, citing a violation of state pollution laws and giving the company two years to fix the problem. Two decades later, another consent order was issued. In 2023, testing showed radium levels were nearly double the 5.0 picocuries per liter limit.

Hilton, the vice president of mining operations at Chemours, blamed naturally-occurring iron and radium for the violations. Chemours mixes effluent from the mines with natural water sources, which it says have high levels of iron, before samples are taken for testing. Studies of the surface and groundwater near the Maxville mines have not yet identified Chemours’ operations as responsible for the radium violations, Hilton said.

“While these studies are still on-going, factors such as ambient low pH levels can influence radium mobility,” he added. “No causal link to our ponds has been established, and monitoring and treatment continue.”

Paul Still, a former plant pathologist, has spent nearly a decade of his retirement attempting to hold Chemours accountable for radium issues. This effort began in 2015, when he started working with Bradford’s Soil and Water Conservation District, a local county board that manages stewardship of the county’s natural resources.

It wasn’t long, he said, before he began noticing the environmental problems with the mine. His first concern was the iron pollution in their water releases, which Still said stained parts of creek beds orange and left plants coated in a fuzzy, white iron-oxidizing bacteria. Soon, he was busy investigating radium-laced flooding from the titanium mine, digging through public records, and sharing his findings in community meetings.

Chemours operates large wastewater treatment ponds that are built within earthen dikes. Before the water is discharged, it may be treated with a number of chemicals, which cause the contaminants to clump together and settle into the mud at the bottom of the ponds. Water that remains after treatment is discharged through designated channels into the nearby environment.

Still worries that high levels of radium contamination are building up in the mucky sediment at the bottom of the ponds and could make its way into floodwaters if a berm overflows or breaks during heavy rainfall. But whether the contaminants are causing health problems for residents has not been studied.

“So much depends on the actual quantities of the radium that are present,” said Ron Cohen, an emeritus professor of environmental engineering at the Colorado School of Mines. “We get exposed to it frequently — it’s in the natural environment. But then again, you can get concentrations of radium that are very high, that almost guarantee you will develop some sort of cancer.”Cohen confirmed that radium and iron pollution often come as a pair, but said he was unable to draw conclusions without visiting the site in question. Because radium can bind tightly to soil, he said, contamination levels could vary significantly depending on the kind of environment a mine’s water is discharged in and how it travels through that environment.

“If I lived near Chemours, I’d be paranoid too,” said John Quarterman, who serves as the Suwannee Riverkeeper, a staff position for an organization of the same name that advocates for conservation of the numerous watersheds within the Suwannee River Basin. “Some of the stuff they’re paranoid about is probably actually happening, but it’s hard to document which of it is and which of it isn’t.”

Until the Florida Department of Environmental Protection takes frequent measurements up and down the state’s rivers, Quarterman said, it will be difficult to pin down the impact of Chemours’ activities. And without such studies, he said, it’s difficult to identify bad actors — let alone hold them accountable.

In Florida and beyond, the regulatory landscape for mineral mining is fragmented, and enforcement is often absent. Congress first passed a law opening public lands to industrial mining in the late 1800s and granted generous rights to the companies who plumbed it, namely the right to stake mineral claims on public lands without paying rent or royalties on extracted resources — which also left the lion’s share of the environmental consequences of mining to the government to deal with.

Over 150 years later, that law has remained largely unchanged and still governs federal mining policy. In addition, federal laws such as the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act can apply to mining activities. But at the local and state level, experts say these policies are often poorly enforced.

Raquel Dominguez, a circular economy policy advocate at environmental advocacy group Earthworks, said this has left mining regulations “just absurdly out of date and archaic.” Even when mining adheres to federal environmental standards, she said, “it still produces hundreds of millions of gallons of wastewater” which can wreak serious, lasting damage to ecosystems.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection largely oversees the implementation of the federal rules at the state level. Under the Clean Water Act, a federal program sets upper limits on wastewater discharge and mandates that companies submit regular self-monitoring reports to ensure compliance with contamination limits. Chemours’ wastewater permits, for instance, specify how much wastewater it can discharge into rivers, lakes, groundwater, and other water bodies.

Although the law allows for exceptions during emergencies, such as a storm or heavy rainfall, unauthorized discharges must still be reported. Once the wastewater is released, neither the company, the Department of Environmental Protection, nor federal agencies seem to publicly monitor or publish information on how far the water travels. That uncertainty matters in a region of closely connected wetlands, rivers, and a vast underlying aquifer.

Read Next This county has an ambitious climate agenda. That’s not easy in Florida.Sachi Kitajima Mulkey

This county has an ambitious climate agenda. That’s not easy in Florida.Sachi Kitajima Mulkey

In March 2025, the company received a warning letter from the Department of Environmental Protection for excess wastewater releases. Emails obtained by activists through Freedom of Information Act requests show Chemours requested to meet with regulators. Separately, six out of the eight inspections conducted at a Bradford County mine by state regulators between 2016 and 2023 found the company was out of compliance with its previous permit. The state’s Department of Environmental Protection did not respond to repeated inquiries by Grist for further information.

Inadequate regulations are often the standard for mining operations across the country, according to Athan Manuel, who directs the Sierra Club’s lands protection program. Some states, such as Maine, have recently passed laws that augment federal legislation like the Clean Water Act that make it difficult to permit new mines and seek to protect clean water from mining discharges. In 2023, the Biden administration released a report calling for the modernization of the Mining Law of 1872 that would ramp up mining claims and permit protections and establish reclamation fees and royalties — but the move yielded no substantive policy changes.

The Trump administration has also continued dismantling whatever environmental protections do exist. In 2019, during Trump’s first term in office, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed a key rule of the Clean Water Act, cancelling protections for millions of acres of wetlands and streams. This past spring, Lee Zeldin, the agency’s new administrator, issued guidance to continue removing clean water protections for certain wetlands. President Trump has also issued an executive order to ramp up mineral mining production nationwide, while his officials recently bypassed federal laws in a multibillion-dollar deal with a company running the country’s only rare earth mine in California.

The anti-mining activists in Florida have had some success fending off mining projects through grassroots organizing. In 2023, a years-long battle over proposed phosphorus mines in the region came to an end when HPS ll withdrew its application to mine in Bradford County. And in June, a conservation group purchased the land that Twin Pines, a company that Chemours formerly contracted with, was attempting to mine for titanium-bearing ores in Georgia’s Okefenokee swamp, effectively canceling that project, too. Chemours also recently came under fire for its continued release of PFAS, or forever chemicals, contamination in the Ohio River, despite a judge’s order and being the subject of the first-ever EPA action against PFAS.

But in Florida, Chemours’ operations have carried on. Recently, the company moved to renew its permit to mine 2,800 acres in Bradford and Clay County. If approved, the mine would continue to discharge wastewater into the headwaters of the Santa Fe River for another ten years. According to the permit application, at least seven species listed as endangered or threatened would be affected by the development.

This moment matters, Still said, because it gives local groups a chance to speak up against the mine’s requests for environmental permits. “There’s no shortage of permits needed for a new project,” he said, listing off the requirements for developments in Florida, which range from the local water management district to the Army Corps of Engineers. “But once they have it, that’s where the system is breaking down,” he said.

The region’s anti-mining activists are gearing up for another long fight — full of public comment periods, requests for information, and community organizing. But if authorities don’t take the steps to address the community’s concerns, Still warned, it will become all the more difficult to focus on the solutions.

Ultimately, what advocates like Carter and Blais want is a concerted effort from local officials to investigate their concerns. Until then, rural Florida communities like theirs will be left bracing for the worst — whether it be an emergency spill during a hurricane or just a routine day of mining.

“It would mean so much to me for somebody to just listen, to know what’s happening to us,” Carter said. “I just think we owe it to future generations to do everything we can to pass them on something that’s worth living in.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Waterlogged and contaminated: In rural Florida, locals suspect a mining company is to blame for their flooding troubles on Sep 4, 2025.

From Grist via this RSS feed