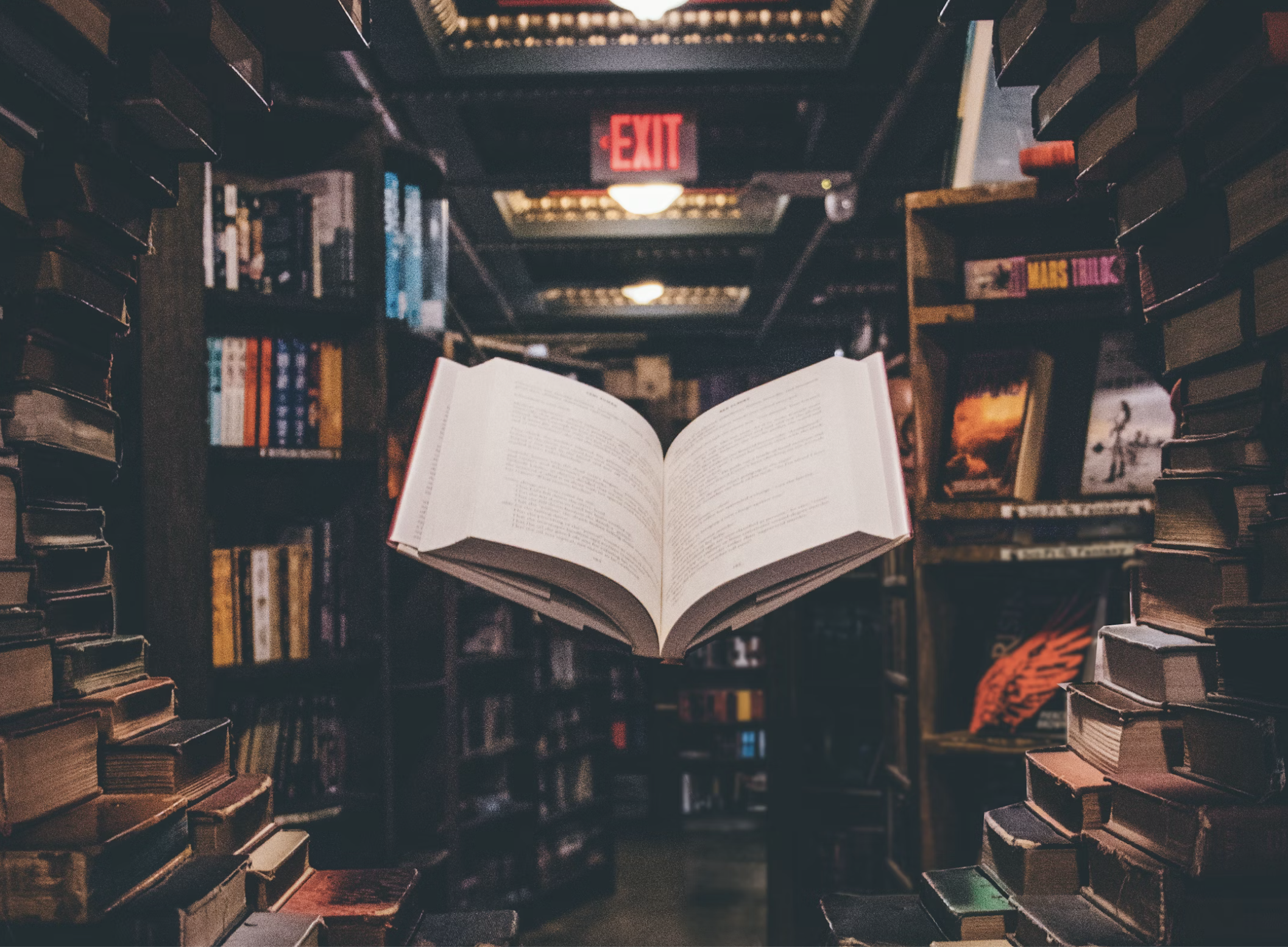

Photo by Jaredd Craig

Ambitious young people are told that a college degree is necessary to launch a successful career. For me — a “lifer” taking courses from my cell in a state prison — higher education isn’t about job preparation but rediscovering my humanity, about learning to think beyond the bars.

I’m not the first person to discover the power of education while incarcerated, but I feel a responsibility to tell this story, not only to reach other prisoners but for all the people who feel left behind by educational institutions. There have been a lot of obstacles between me and higher education — times I didn’t believe in myself and times when institutions didn’t believe in people like me — but I have learned that no one has to settle for that.

Let me start with a stereotype of young Black men — that they think excelling in school is for nerds, not for tough guys on the street. That doesn’t describe all Black boys, of course, but it was true of the guys I ran with. I had loved learning when I was younger, but a combination of institutional failures and peer pressure knocked me off that path. I regret giving up so easily, which was reinforced by a school system that didn’t seem to care much about Black children. I ended up in that “school-to-prison pipeline” for the poor and marginalized.

A series of bad choices as a young adult led to my current residence in the Washington Corrections Center, serving a life-without-parole sentence. While incarcerated, I became a “better late than never” enthusiast for higher education.

But the prison system hasn’t made that easy. The tough-on-crime politics of the 1990s produced the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act in 1994, which eliminated almost all financial aid to prisoners. (It was only in 2023 that prisoners once again became eligible for Pell Grants.)

In 1995, Washington state passed a law that prohibited public funding to support higher education for prisoners beyond adult basic education and the General Education Diploma (GED). Prisoners who had been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole were denied access to more than one post-secondary degree, unless it was pre-vocational or vocational training was needed for their work in prison. The legislation was supposed to eliminate “unnecessary” spending by the Department of Corrections. (That law was partially repealed in 2017, allowing some funding up to two-year degrees.)

Tough-on-crime laws — including “Three Strikes, You’re Out” and “Hard Time for Armed Crime” — led to larger prison populations in Washington state and around the country. Access to education was not a priority, and budget cuts after the 2008 recession led the Department of Corrections to prioritize education for prisoners with less than seven years on their sentence. The rest of us were out of luck.

Don’t ask me to explain how that fits with the rehabilitation mission of prisons — people who are incarcerated know the gap between that rhetoric and the reality of warehousing prisoners. That’s why incarcerated people have done much of the work themselves, one of the most exciting aspects of my experience.

My introduction into higher education began in 2015 through my experience with the TEACH program (Taking Education and Creating History) at Clallam Bay Corrections Center, another prison where I was incarcerated. TEACH was created in 2013 by the Black Prisoners Caucus to address the educational disparities that exist within the prison system for minority, long-term, and undocumented prisoners.

That experience helped me rediscover my humanity.

At that facility, we had a healthy working relationship with prison officials, who gave us classroom space. Through TEACH, we were able to develop and facilitate the courses we needed. We understood that the educational system had left most of us behind, and I learned that some of us came with life experiences and credibility that some of the most decorated professionals did not have.

But we couldn’t deepen our knowledge from experience without help. TEACH leaders established a relationship with Peninsula College and Seattle Central College. For me, getting ready for college-level study took some work.

Before I could start taking college courses, I needed to earn certificates in college-prep math and anger management. After the completion of those two nine-week courses, I took African American studies, a parenting class, and college-prep writing. Then I felt ready to take my first college course through Seattle Central. That sociology class required a lot of writing, which was intimidating at first, but I loved what I was learning, and that course showed me that my experience was shaped by larger social forces.

At the beginning of my college journey, I was uncertain of my ability, an insecurity rooted in so many bad experiences in school. But TEACH had helped me believe in myself, teaching me not to accept the limits of the bars I lived behind, and eventually I was able to start giving back to the program. I was given a chance to facilitate the stress and anger-reduction class I had taken, which led to me joining the program’s board at Clallam Bay. After being transferred to Washington Corrections Center, I was elected vice chair of the program when it was brought to that prison in 2018.

As I worked with the program, I learned my experience was not unusual.

I talked with Thomas Mullin-Coston, a prisoner-student who went on to create and facilitate a sound and song-production course at WCC, which taught prisoners to play and create songs on a keyboard. He said that initially he wasn’t sure he could teach a class, let alone one that he created. TEACH helped him gain the confidence he needed, encouraging him to teach the course the way he thought best. More prisoners sought his expertise, deepening his confidence.

Dwuan Conroy, another TEACH student, said that in addition to the direct benefits for him, the funding for this program took the burden off his wife and family to pay for his education. And when he is released, his enhanced ability to set goals and meet deadlines means that he’ll have a chance at better paying jobs. And, he said, it shows his family that he is making the changes needed to be a better man.

Unfortunately, six months later Mullin-Coston’s sound course was canceled, because it was “not serving a facility need.” That is an example of short-sighted decision-making. If we care about rehabilitation, any learning that creates a positive environment and promotes healthy interactions among prisoners should be seen as a crucial facility need.

The COVID pandemic also created obstacles, shutting down the WCC TEACH partnership with Centralia College and Seattle Central. Conroy was enrolled in courses in biology, anthropology, and English, but lockdowns meant that formal classes were canceled. With little help available from teachers and staff, he said, the prisoner-students relied on each other to finish courses.

“It was these interactions with other prisoners that helped me through the course work despite my learning disabilities,” Conroy said. ”Knowing I had others around in TEACH that could help me through it and not judge, that empowered me to continue my focus during such a difficult time.”

Once the college’s staff members where allowed back into the prison, it was clear that our peer-support work had been crucial in keeping us on track, and 10 students graduated in the fall of 2023.

Taxpayers and politicians who prioritize punishment over rehabilitation may not care about how education enhances prisoners’ mental health and intellectual development. Once again, that’s short-sighted, because education also reduces recidivism. For every dollar spent on education programs, four dollars are saved on re-incarceration costs. One study showed that prisoners who complete some high school courses have a recidivism rate of 55 percent. Vocational training cuts recidivism to 30 percent, an associate degree to 13.7 percent, and a bachelor’s degree to 5.6 percent. A master’s degree brings the recidivism rate down to zero,

Prison education is not a frivolous expense for society but instead an essential investment in human beings. Education reduces conflict among prisoners. Communities are safer when educated and empowered prisoners return home.

As for me, I need two classes to earn my associate degree, after which I want to pursue a bachelor’s degree in behavioral health, and perhaps a master’s degree someday. I still live behind bars. But developing my mind has helped me find the humanity in myself and see more clearly the humanity in others as well.

The post Thinking Beyond the Bars: How Higher Education Helped Me Develop Confidence in Myself and Rediscover My Humanity appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed