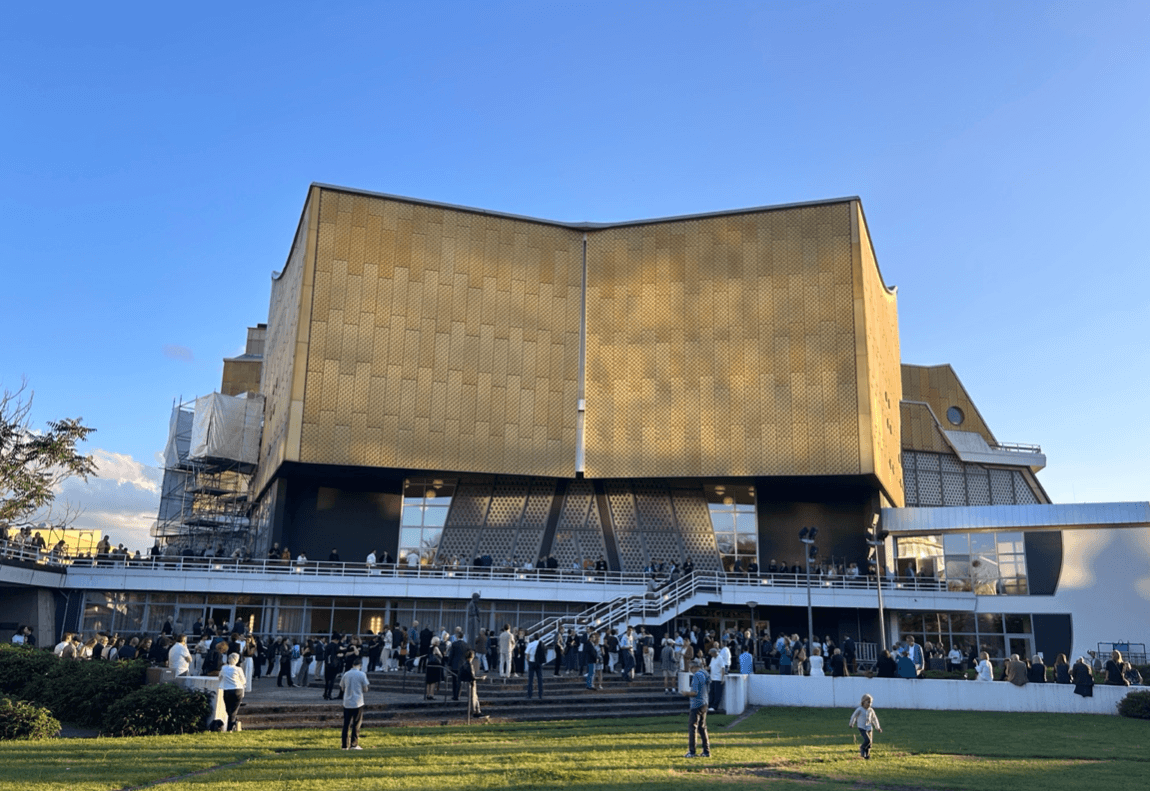

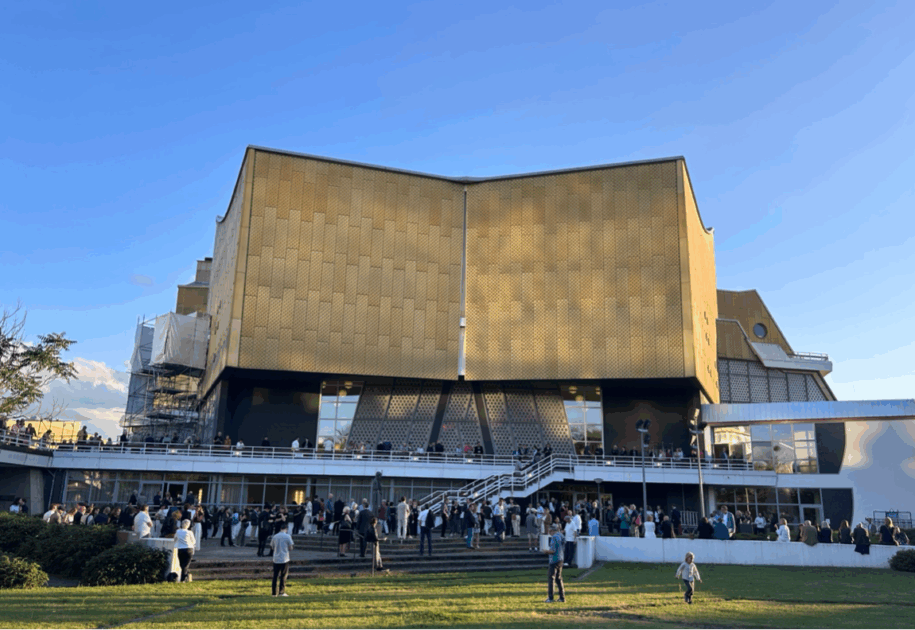

The Philharmonie, Berlin. Photo: David Yearsley.

Midway through its near non-stop, culture-packed calendar running from August 30th to September 24th, the Berlin Musikfest last weekend brought two French symphony orchestras to the German capital’s famed concert hall, the Philharmonie. On Friday, the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées did Beethoven and Cherubini. On Saturday, a doubleheader from Les Siècles re-revolutionized Beethoven and Berlioz at 6pm, then re-modernized Boulez in a second concert later that same evening. This embarrassment of French riches came just a week after the Orchestre de Paris had made its appearance at the festival, thus bringing the total to three Parisian ensembles to match the three from Berlin also on the Musikfest roster. The ambitious program is filled out by orchestras from Korea, Sweden and Italy.

These bands are big. The Big Band of the German Opera Berlin, which plays tomorrow night, is smaller. The musicians and their repertoire are diverse; the interpretations vigorous and varied; the carbon footprint enormous.

I came to the Philharmonie as always on my bike—not much of an offset for enjoying the musical armies and their instrumental arsenals flown in from around the world. In Berlin, the land is flat, the few hills manmade, the moral high ground non-existent.

The back-to-back Beethoven-plus-epigone outings of the Orchestre de Champs-Elysées and Les Siècles made for a study in similarity and contrast.

Both groups are packed with virtuosos who subordinate their skills to the musical goals of the whole. Both use period instruments, either antiques made during or near the time when the composers wrote the music performed, or new ones modelled on the originals. Both ensembles explore the new creative avenues opened up when modern musicians wield old tools to confront the classics.

In Berlin, one of the orchestras was led by a young conductor with panache and precision. The other struggled to overcome the palsied trepidation of its flagging director.

Founded in 1991, the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées concentrates, as it did last Friday, on repertoire composed between 1750 until about 1900. Les Siècles has been around since the first years of this millennium, and, as the group’s name promises, it ranges across more centuries than its Parisian counterpart, from the 17th into the 21st.

Finicky forbear violins and willful winds had, on their first rediscovery, generally demanded specialization, but Les Siècles and its members are a leading a movement within a movement the Early Music movement intent on busting down barricades and opening up possibilities. Indeed, Les Siècles takes scholarly reconstruction and technical mastery to new levels of encompassing exactitude. For their program of Beethoven and Berlioz the wind players had to bring a quiver of flutes, oboes, and clarinets, shotgun cases of bassoons, oversized golf bags of oddities like the ophicleide and serpent. The concert program booklet not only listed all the musicians and but also all their instruments, as if to say that they, like American corporations, are people too.

At the top of the list was the flutes. The program informed us that the instrument used for the Beethoven was made by Rudolf Tutz after a Heinrich Grenser original from around 1810 with eight keys (seven more than a century earlier). Twenty-four years on and an unspecified number of added keys later, the Berlioz required one by Gautrot Aîné and another rom Jeanl-Louis Tuulou, both from 1845—apparently a good year for flutes. The orchestra’s pitch standard had to be re-calibrated during the intermission, inching inexorably upward from 430Hz to 438.

Last on the list of instruments came the mysterious serpent, which, along the course of its four oxbow bends that lead from mouthpiece to bell, expands from rattlesnake to python girth. The exemplar heard in Berlin last weekend was a modern reconstruction based on a 19th-century original by someone called Baudin—perhaps a hero to select devotees and practitioners of the instrument, but utterly meaningless to me and most others. Still, the reference might charm some kid in the audience into taking up the musical snake. In 1770, sixty years before the Symphonie fantastique was premiered in Paris, the Englishman Charles Burney stamped scornfully on the serpent while travelling through France, calling it “detestably out of tune, but exactly resembling in tone that of a great hungry Essex calf.”

Yet in his massive menagerie of winds Berlioz made sure to include the cantankerous beast. In the fifth and final movement, the slitherer intones the ponderous, portentous Gregorian melody of the “Dies irae” (Day of Wrath) along with a pair of ophicleides (like lanky tubas) as well as chimes whose ringing summons thoughts of churchly judgement and eternal doom. The program did not divulge the name of the serpentist, but when he held up his instrument during the ovation afterwards, there was a surge in the applause as if he were brandishing a real snake that might escape his grasp and wriggle out into the packed auditorium to liven up the après party.

For the Berlioz the Philharmonie stage was more crowded than the observation deck on Noah’s Ark at cocktail hour: four harps (deployed only in the second movement; Berlioz’s opium-sparked mania for orchestral color and scope had extinguished all regard for hand-luggage guidelines in the then-as-yet-imagined age of international orchestral tours; the stagehands who removed the harps before the third movement got a hilarious round of applause for their perilous efforts); gaggles of winds; throngs of strings; and a herd of percussion gathered around four timpanists.

Les Siècles await their conductor, Ustina Dubitksy, for Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique in the Berlin Philharmonie, September 6th. Photo: David Yearsley.

The leader of this last contingent was percussion prodigy Camille Baslé. He was almost as fun to watch as he was to hear. His facial expressions oscillated between smiles of boyish wonder to madcap surprise to sublime reflection. Sometimes he swayed in his chair when not playing, gesturing and nodding at his compatriots alongside when they joined together, but also conversing through his movements as much as his mallets with the young Bavarian conductor, Ustina Dubitksy not far away, as the timpani was nestled close in behind the second violins rather than relegated to the back of the stage as is normally the case. Whereas Berlioz had been an infamously demonstrative conductor, Dubitsky is dynamic yet controlled, intent on drawing expression from her players rather than attention to herself. She practices an elegant accuracy, favoring efficient, meaningful gestures over maestro man-spreading, groping fingers and fist-pumping. She knows when to pick her spots to extend, enthuse and elevate.

On a different set of timpani, Baslé had been a heroic yet sensitive force in the Beethoven violin concerto, its demanding solo part conquered with a thrilling mix of majesty and intimacy by local heroine and international star, Isabelle Faust. She plays the Stradivarius “Sleeping Beauty” of 1704 on loan to her not by Disney but the German bank that owns it. The instrument’s bona fides weren’t printed in the book, but in her grasp the Strad galloped through the passagework, dashed off the martial double stops and saber-rattling octaves, and urgently whispered select high notes whose pianissimo could be heard in the last row of the hall with its miraculous acoustic. With a timeless and timely humanity, she proclaimed the work’s indomitable themes.

Beethoven’s cadenza for the first movement defies concerto codes by introducing a rustic duet between timpani and violin, a dialogue that resounds with space and possibility promised by the escape from convention. Who needs a symphony orchestra when Baslé and his Wunderlich timpani could evoke landscapes, deeds, qualities and characters, life and liberty, as vividly as dozens of other instruments capable of melody? Under Dubitksy and the likes of Baslé, Faust, and the rest of the Parisian centurions, the collision of Beethoven with Berlioz yielded a supernova. By taking seriously history’s materials, by gathering up past aesthetic innovations as fuel to fire the present, Les Siècles kindled rapture and revelation in this concert not just of the centuries but for the ages.

On Friday night, though, the Parisians of the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées saddled up Beethoven’s revolutionary warhorse with a weary warrior in the person of their conductor, Philippe Herreweghe.

The third symphony, nicknamed the Eroica, was originally dedicated to Napoleon when he was Europe’s republican poster boy but was supposedly torn off the manuscript by the composer when the diminutive dictator crowned himself Emperor in 1804.

Decried by some critics at the time as a fantasy rather than a symphony, the Eroica surges with revolutionary intent. Yet Friday’s conductor, the hunched and septuagenarian Belgian, Herreweghe, kept trying to tamp down the forces of musical change with his slight, nearly imperceptible motions. He tickled the air as if it was painful to his fingers, lowering his arms to plead for more quiet. Those under his dubious command occasionally rattled their sabers meekly but never charged the barricades.

Trained as a psychiatrist, Herreweghe barely bows and seems to abjure recognition. He’s reluctant to engage with his audience, or even, it often seems, his musicians, at least in performance. He must do his real interpretative work in rehearsal, but in concert, he conducts as if he is afraid. He enters the stage as if he were slinking into a confessional booth, not mounting a podium. Rather than stretching out on a shrink’s couch, he’d be more inclined to crawl under it to hide. Modesty is to be praised, especially among the ranks of the sex-power-fame hungry ranks of conductors, but timidity in this case resulted in lackluster, sometimes ragged results. This Beethovenian revolution was a tea party—and a tepid one at that.

Composed in 1816, the year after Napoleon’s final abdication, Cherubini’s Requiem, which made up the second half of Friday’s concert, was celebrated in its time, a multi-opus monument to revolution, war, monarchic restoration, and heroic remembrance. Such was the work’s fame and purchase that Beethoven wanted it to be played at his own funeral. The choir for the Cherubini was the Collegium Vocale Gent, which Herreweghe himself founded five-and-a-half decades ago. This group could not be quelled by their director’s shy fragility, as if thirty some human voices gathered together as one singing from the collective unconscious. Rays of hope and color shone from shadows.

But one still must wait for some other irreverent, but informed, authenticists like Les Siècles to take a power-washer to the mossy emotional architecture of the Cherubini crypt and reveal its majesty and emotion.

In the reddening haze of climate apocalypse, Beethoven seems to strive not so much to overcome the looming cataclysm as to search for an aestheticized acceptance of it. The music’s fire doesn’t burn the skin, but it is real, whether dampened by Herreweghe, or released in all its glorious, renewable power by Les Siècles.

The post The Agile and the Aged: Paris Comes to Berlin’s Musikfest appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed