For Joe Minter, the African Village in America, and 1504

And when those white-sailed ships piled us together, cargo in the hull of hell, the word rode with us, our tongues anointed with the power of God. When the lash found our language, when they said don’t read or write, our tongues were still gilded with a heavenly word. We still sang that holy song, even in this strange land. Even here, God spoke to us and through us. Our hands made language and earth became fruitful, and song became prayer, and a people made do with the bones and scraps of america.

And we became messengers with each sin pitched against us— in Birmingham, there was God in the feet of the marchers and in the starched collar of Fred Shuttlesworth, in the curls and dimples of those four girls, in the boyish joy of Virgil and Johnny before their song was cut short.

Messengers, all of us, speaking the word God left us in this weary land. Messengers with the word as their spear, messengers speaking life into each brick, each crop, each stitch, each book we made.

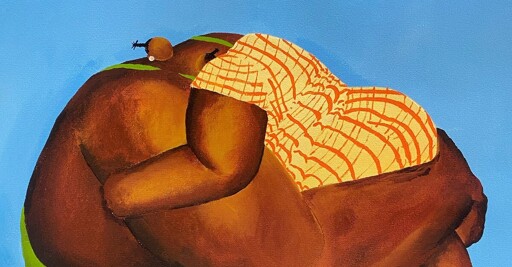

And there is a messenger on Nassau Avenue with the word clear and strong on his tongue, a warrior for the Lord, a servant of the word. And the ancestors find his brown hands and anoint them, and metal becomes message; wood and paint interpret scripture, the wind blows through, and there is God.

In the beginning there was the word, and the word remains. We are a living tongue— the word is a torch and we tote it proudly, what you hear is our collective soul, what you see is love walking, God’s blueprint, ours is an unstoppable song.

This poem is from Ashley M. Jones’s new book, Lullaby for the Grieving.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed