Redford in shades, lower left, his dark-haired nemesis, upper right.

“If you see anyone not mourning the death of Robert Redford the way you would like them to, please call their employer and get them fired!”

– Covie93

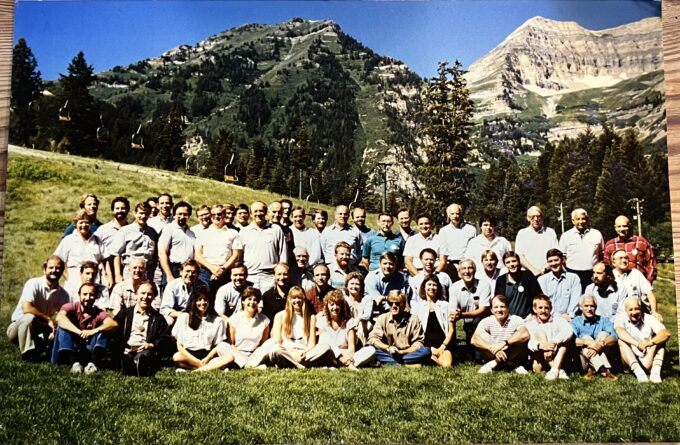

I met Robert Redford in 1986, when Redford thought he could use his personal charm to resolve the fight over the future of the National Forests, which had intensified after the late, great federal Judge William Dwyer issued his first injunctions halting timber sales in Spotted Owl habitat. So he summoned the bigwigs in the timber industry, the environmental movement, the Forest Service and the Bush Administration to Sundance for a long weekend to hash things out over steaks, French wine and long hikes on the flanks of Mt Timpanogos. Redford floated through the gathering in a cloud of beautiful young women as if he were a mountain deity surrounded by mountain nymphs, each one of whom probably had a Ph.D. in ecology from the Yale School of Forestry. Each side played nice for a blissful few days in the Wasatch, then went back to ripping each other’s throats out when they got home. So much for consensus.

I had two more encounters with Redford over the years. Both of them involved trout streams and internationally-known professors of literature at the University of Chicago. In the fall of 1995, I got word from sources in Montana that Redford the environmental champion was sending out fundraising letters for the state’s perpetually embattled Democratic Senator Max Baucus, despite the fact that Baucus had a dismal environmental record and his family had a stake in a giant open-pit gold mine slated to blasted into the headwaters of the Blackfoot River, a sacred stream to anglers around the world and the subject of Norman Maclean’s celebrated novella, A River Runs Through It, which Redford had recently made into an Academy Award nominated film. ) This is the very gold mine that may have set-off the Unabomber, brooding over the toxic monstrosity from his cabin in Lincoln.

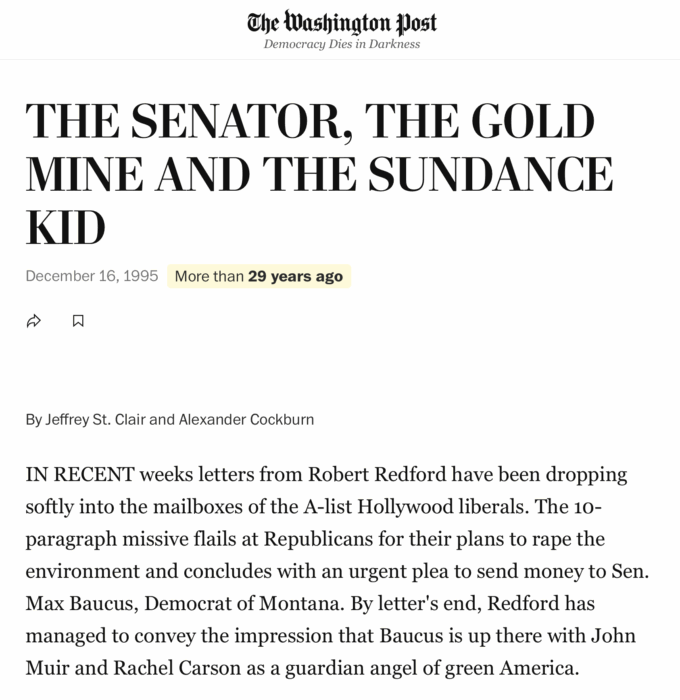

The hypocrisy here was too ripe to pass up, so Cockburn and I investigated further and pitched the story to Jefferson Morley at The Washington Post, where it was eventually printed as the lede story in the Sunday Outlook Section on December 16, 1996.

Redford wasn’t pleased and griped that we hadn’t given him a chance to exculpate himself, although his letter spoke for itself and our repeated attempts to reach him had failed because he was spending the holidays on some remote Hawaiian Island beyond the reach of phone, telegraph or passenger pigeon. I reread the piece the day Redford’s death was announced and was bemused to find that it’s one of the very few occasions in the hundreds of articles and a dozen books we wrote together over 20 years when I got top billing on the byline ahead of my more famous/infamous co-editor, who always justified putting his name first because “C comes before S, Jeffrey. You know that.”

I didn’t receive another personalized invitation to Sundance (Oh, the Sting!), but a few months later, I did get a letter from one of Norman Maclean’s old friends, the acclaimed literary theorist Wayne Booth, who, like Redford, was a native Utahn. Booth was born and raised in American Fork Canyon under the shadows of Sundance Peak and Mt. Timpanogos. Booth, who had taught at the University of Chicago with Maclean, kept a summer place in the canyon and invited me out to Alpine, Utah, to show me how raw sewage was leaking down from Redford’s supposedly benign Sundace resort into the trout streams of the canyon and the American Fork River itself. I wrote up the malodorous saga for Our Little Secrets (the precursor to Roaming Charges) in the old CounterPunch newsletter, earning me the lasting enmity of the Sundance Kid, America’s last real movie star. – JSC

Still from Robert Redford’s film A River Runs Through It.

The Senator, the Gold Mine and the Sundance Kid

by Jeffrey St. Clair and Alexander Cockburn

December 16, 1996 Washington Post

In recent weeks, letters from Robert Redford have been dropping softly into the mailboxes of the A-list Hollywood liberals. The 10-paragraph missive flails at Republicans for their plans to rape the environment and concludes with an urgent plea to send money to Sen. Max Baucus, Democrat of Montana. By letter’s end, Redford has managed to convey the impression that Baucus is up there with John Muir and Rachel Carson as a guardian angel of green America.

If Baucus needs a star to rouse sympathetic liberals, Robert Redford is certainly the ideal man to pitch his virtues. Redford lives on a ranch in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains and funds environmental causes through his Sundance Foundation. Since he filmed Norman Maclean’s trout-fishing novel “A River Runs Through It,” the Sundance Foundation has given large amounts of money to Blackfoot Challenge, an organization set up to protect and restore Montana’s Blackfoot River, the stream that runs through Maclean’s book.

In a recent speech before the National Press Club, Redford spoke out passionately against the mining companies: “I can only believe that their bottom lines will win out over the health of our lands and our people. I’ve already seen enough bright orange rivers with no fish, thanks to mining companies who swore their operations were safe — like the Blackfoot, for example, in Montana.”

Yet Max Baucus, the beneficiary of Redford’s fund-raising, is an unrepentant, self-described “friend of mining” who stands to profit personally from what is being heralded as the largest open-pit gold mine in North America — which will be located in the headwaters of Redford’s beloved Blackfoot River.

Phelps Dodge, the mining colossus that will operate the mine, says that roughly a billion tons of dirt and rocks will be gouged and blasted out, crushed, dumped into heaps, and then saturated by water laced with cyanide, a process that leaches small flecks of gold from tons of rock. By the time the mine, known as Seven-Up Pete, is tapped out there will be a hole in the earth more than a mile across at one point and 1,000 feet deep. And when the gold runs out in 12 years, Phelps Dodge and its minority partner, a Colorado-based gold mining company called Canyon Resources, will leave behind cyanide-sodden dirt for all eternity, just a few hundred feet from what may well by then be the lifeless waters of the Blackfoot River. Aportion of the mine’s operations will be on land that belongs to the Sieben Co., an 80,000-acre sheep ranch owned by the Baucus family. The Baucus clan now stands to make a great deal of money, since the Sieben Ranch will take home 5 percent of the gross value of any minerals extracted from their land. Phelps Dodge and Canyon Resources expect to gross at least $4 billion overall from the mine.

Landusky Gold Mine, northern Montana.

The Sieben Ranch is managed by the senator’s brother, John Baucus Jr., who also serves as president of the Montana Wool Growers Association. Max Baucus maintains a financial interest in the ranch and receives regular dividend checks from the company.

Asked for his views on the effect of the mine on the Blackfoot, Baucus responded with a written statement saying, “I have a great love and respect for the Blackfoot River, its heritage and its history. Because of the sensitivity of the upper-Blackfoot, if this mine is to proceed I think it should meet a high standard of environmental protection.” Baucus earlier issued a similarly pious statement about the Crown Butte mine near Yellowstone National Park.

Given the awesome amount of boodle due to be collected by the Baucus family, it is not hard to understand why the senator is demure on the subject of Seven-Up Pete. It is harder to understand why Redford is raising money for Baucus. Redford knows first-hand the threat to the Blackfoot. When he came to Montana to film “A River Runs Through It” in 1992, the river had been badly trashed by logging and by mining. There were few trout left and the river’s canyon was heavily scarred with clear-cuts. So Redford shot many of the film’s scenes on the Yellowstone and Gallatin rivers farther south.

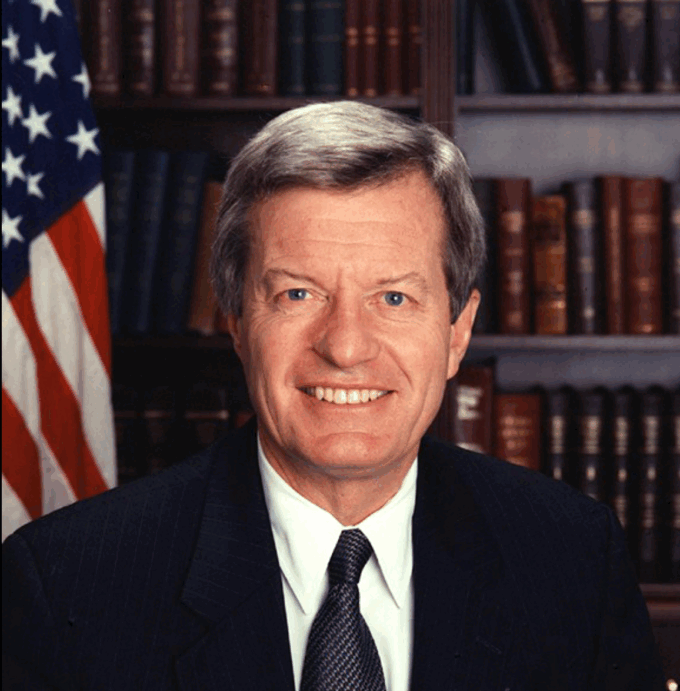

Max Baucus.

Over the past few years, though, the Blackfoot River has been starting to heal, thanks largely to the aggressive work of local environmental groups, such as the Clark Fork Coalition and the Montana Environmental Information Center. Now, just as some cutthroat and bull trout runs have returned, progress is endangered. Already exploratory excavations at the Seven-Up Pete site have resulted in the state-approved dumping of millions of gallons of arsenic and lead-contaminated water into the Blackfoot. The larger story here is Baucus’s career role in fighting off environmental regulation. Across the length and breadth of Congress it is impossible to uncover a more tenacious front-man for the mining, timber and grazing industries. For example, it was Baucus who crushed the Clinton administration’s timid effort to reform federal mining and grazing policies and terminate below-cost timber sales to big timber companies subsidized by the taxpayers. In March 1993, Baucus engineered a session at the White House with Mack McLarty, Clinton’s then-chief of staff, and emerged boasting to a Washington Post reporter that this was the last time the Clinton crowd would dare to try and cram public land reforms down Western throats.

Nothing new here. Back in 1991, Baucus voted to kill a bipartisan effort to place a moratorium on the sale of mineral-rich federal lands to multinational mining companies for $5 an acre; the moratorium failed by one vote.

Baucus also has a deep personal interest in the present perquisites of the Western ranching industry. The Sieben Ranch is also one of the largest sheep operations in North America and it enjoys an exceptionally close and profitable relationship with public grazing lands adjacent to the ranch and administered by the U.S. Forest Service. Here, Baucus sheep graze for the standard federally subsidized rate of 22 cents per animal per month, less than a fifth of the going rate on private lands.

Blackfoot River, near Lincoln, Montana. Still from the documentary, Mining Seven-Up Pete.

One of the grazing permits held by the Sieben Ranch is in the Helena National Forest. This wild landscape is home to the threatened grizzly bear, fewer than 800 of which now survive in the Lower 48. The Baucus family ranch holds one of Montana’s only remaining sheep grazing permits in critical grizzly habitat. This is not a happy situation for the bears, since they like to eat sheep and when they do, the ranch manager calls in the government hunter, who duly shoots the perpetrator with sodium pentothal and exiles the bear to another area.

If the bears return, as they sometimes do, they are either captured and placed in a zoo or, more typically, just killed. That’s why sheep grazing permits have been denied in other federal forests in Montana occupied by grizzlies. According to Fish and Wildlife Service reports, there have been four non-natural deaths of grizzly bears on Sieben Ranch allotments since the mid-1970s when the bear was protected as a threatened species. A representative of the Sieben Ranch did not respond to inquiries about grizzly mortality on company grazing land.

Baucus has also criticized local environmentalists for using Hollywood celebrities, such as Woody Harrelson and Glenn Close, to promote their campaign for the ecosystem.

“National money, glitz and glamour are reaching into Montana,” the man who has now corralled Robert Redford as a fund-raiser warned in June 1992. “These interests, mostly based out of California, are doing all they can to see that Montana’s 12-year civil war over the wilderness issue continues on and on.”

Baucus scarcely needs money from the Hollywood liberals. In his last re-election run in 1990 he was the second largest recipient of PAC money in the Senate: $1.86 million in a state with fewer than 500,000 registered voters. What Baucus needs from Redford is political cover. The big question is why Redford is providing it for him. Redford declined to respond to questions about Baucus and the gold mine. An aide to Redford said that the actor (like the national environmental groups based in Washington who have also raised money for Baucus) is willing to work with him because he is a Democrat and any Republican who replaced him would be worse.

But Redford’s fund-raising letter doesn’t even brave that argument. Redford does not excuse Baucus as the lesser of two evils but hails him as a true friend of nature. The Sundance Kid should go back to the Blackfoot and take one last look.

The post The Senator, the Gold Mine and the Sundance Kid appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed