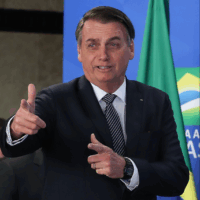

Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro using his “finger gun” gesture. Photo: Marcos Corrêa/PR, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0

The line smoulders, the rhyme explodes— and by a stanza a city is blown to bits.

– Vladimir Mayakovsky

Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil; who put darkness for light, and light for darkness; who put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter.

– Isaiah 5:20

When a far-right influencer is shot dead in broad daylight in the United States, the result is not mourning but spectacle. The new faceless Leviathan of digital platforms transforms the still-warm body into content, and the crime into clicks. Within minutes, disinformation starts writing its own narrative: the killer is a leftist, a “woke agent”, the perfect scapegoat-fuel to keep the flame of falsehood burning. But the truth, always more prosaic and less profitable, reveals that the perpetrator is from a stalwart Trumpist Republican, pro-gun family which also feeds at the trough of clickbait hate.

Herein lies the cruellest irony: the dead man advocated proliferation of weapons and violence as a way of “defending freedom”. He died by this logic, victim of his own fetish. But what matters is not only the death itself but also the way it burgeons in the attention economy with more polarisation, more engagement, and more profit for the platforms. This is platform capitalism at its most dangerous. It both mirrors fascism, and engenders it. Just as early 20th-century industrial capitalism fuelled Nazism and two world wars, this new capitalism based on surveillance, data capture, and manipulation of emotions is the machinery of the new global far right.

I’ve been calling this psycho-political state in which individuals not only consume disinformation but also find in it a sense of belonging “cult subjectivity”. This isn’t mere mistaken belief but a way of life. Belonging to these digital cults—whether QAnon in the US or Bolsonarism in Brazil—replaces social, family and institutional ties. It produces a totalising identity, impervious to dialogue, and willing to sacrifice even its own life and certainly the lives of others. It was this subjectivity that led mobs to invade the Capitol in Washington and the Three Powers Square in Brasília. It was this subjectivity that brought tens of thousands onto the streets of London in an unprecedented anti-immigrant march, led by Tommy Robinson, a central figure of the British far right. And it’s the same logic that fuels the unrest in Nepal, where Hindutva nationalist groups connected to Modi’s BJP and inspired by anti-Muslim rhetoric have been promoting attacks on ethnic and religious minorities, and importing tactics and narratives from global disinformation networks.

In Brazil, this kind of assemblage is well known. The MBL (Free Brazil Movement), along with Nikolas Ferreira, Carla Zambelli, and Allan dos Santos, forms a professional network for disseminating disinformation and virtual lynchings, in collaboration with international thinktanks and influence groups. In the United States, Ben Shapiro, Jordan Peterson, and Steve Bannon daily feed the digital masses with content that mixes resentment, punitive moralism, and supremacism dressed up as defence of freedom. In Spain, Isabel Díaz Ayuso and Santiago Abascal are perfect puppets for a project that combines lawfare, culture war, and xenophobia. In the United Kingdom, Nigel Farage reappears whenever necessary to stoke hatred of immigrants and keep the Brexit flame burning. In France, Marine Le Pen postures as a “moderate” to normalise what was previously unacceptable. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni, now Prime Minister, transforms what was once merely far-right rhetoric into state policy: xenophobia, misogyny, and the cult of the “traditional” family.

Falsolatry—a concept I use in my book of the same title—is collective worship of lies when they become more functional and pleasurable than truth. In platform capitalism, lies have exchange value. They circulate more, engage more, and monetise better. The temple of this religion is algorithms. The misinformation surrounding the murder of the American influencer is exemplary. Even before the police released the shooter’s name, memes, videos, and threads were already circulating on X and TikTok associating the crime with the left, immigrants, and minorities. Subsequent fact-checking doesn’t stand a chance against the pleasure of sharing a “version” that confirms only the reality of pre-existing hatred.

Traditional journalism, which could function as a civilising barrier, has fallen into the trap of false symmetry. In the US, journalists feel obliged to present “both sides”, even when one of them is denial of the democratic regime itself. The pattern repeats itself in Brazil. Bolsonaro and Lula are positioned as comparable sides of the same balance, when one of them was responsible for more than 700,000 preventable deaths during the pandemic, attempted a coup d’état, and established his own personal hate cabinet. This same logic operates internationally. Western coverage of the ongoing genocide in Gaza—and I use the term “genocide” as defined in the lawsuit South Africa is bringing against Israel in the Hague Tribunal—keeps equating the State of Israel, a nuclear power with an ultramodern army that occupies and bombs, with a terrorist group like Hamas. Images of children buried in rubble are framed as “collateral tragedies”, while opinion columns speak of the “complexity of the conflict”. The result is moral anaesthesia.

Journalism financed by clicks cannot but follow the same logic as platforms when prioritising content that provokes a reaction. Hence the reliance on scandal, on the “give and take” caricature. The consequence is erosion of the very idea of factual truth which, as Hannah Arendt said, is a prerequisite for any politics. Without it, we are left with the discursive “anything goes” on which the far right thrives.

What could halt this cycle? First, containment of digital platforms by means of regulation that mandates algorithm audits, cutting off cash flows of persistent disinformers, and radical transparency regarding recommendation criteria. The European Union is beginning to follow this path with the Digital Services Act. It is still tentative, but at least it’s a start. Second, strengthening democratic institutions. Brazil sets an example by putting Bolsonaro and his accomplices on trial. This is not “revenge” but defence of rule of law. Without accountability, impunity becomes an invitation for further attacks on democracy. Third, the recovery of journalism as a public service, funded not by clicks but by collective interest. Without this, we will remain hostage to the algorithm.

In the US, there is already open talk of civil war. In Brazil, extremism remains active and armed. In Europe, the far right is growing in the vacuum of social democracy. In South Asia, ethnic nationalism threatens to plunge entire countries into chaos. History teaches that when barbarism is organised, democracy alone is not enough: it requires collective action, resistance, and intellectual courage. Platform capitalism has turned violence into a business. It is up to us to decide whether we will remain passive consumers of this spectacle or whether we erect—now—the barriers that can save what remains of our fragile democratic civilization.

The post Millions of Likes: The Business of Violence in the New Fascist International appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed