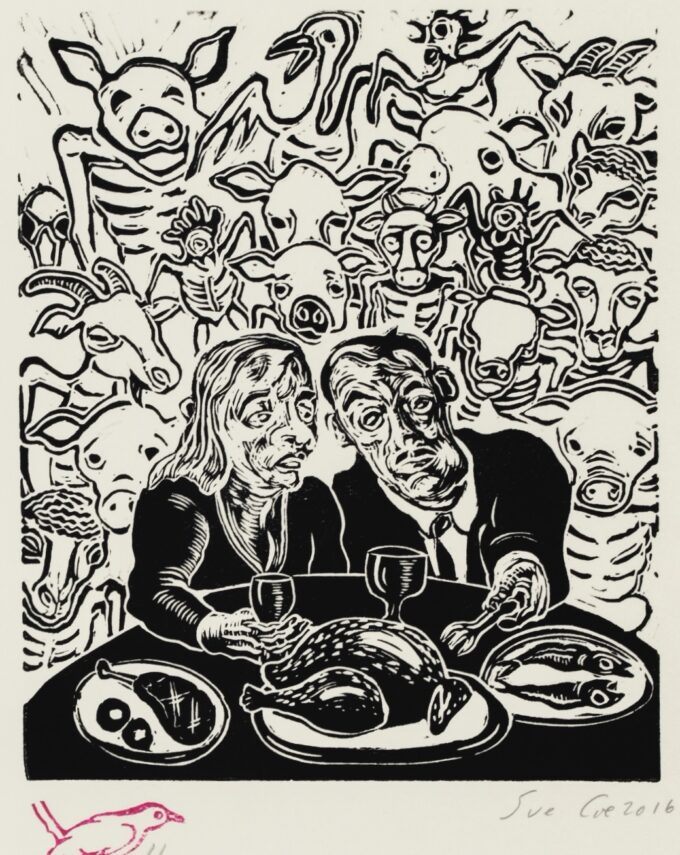

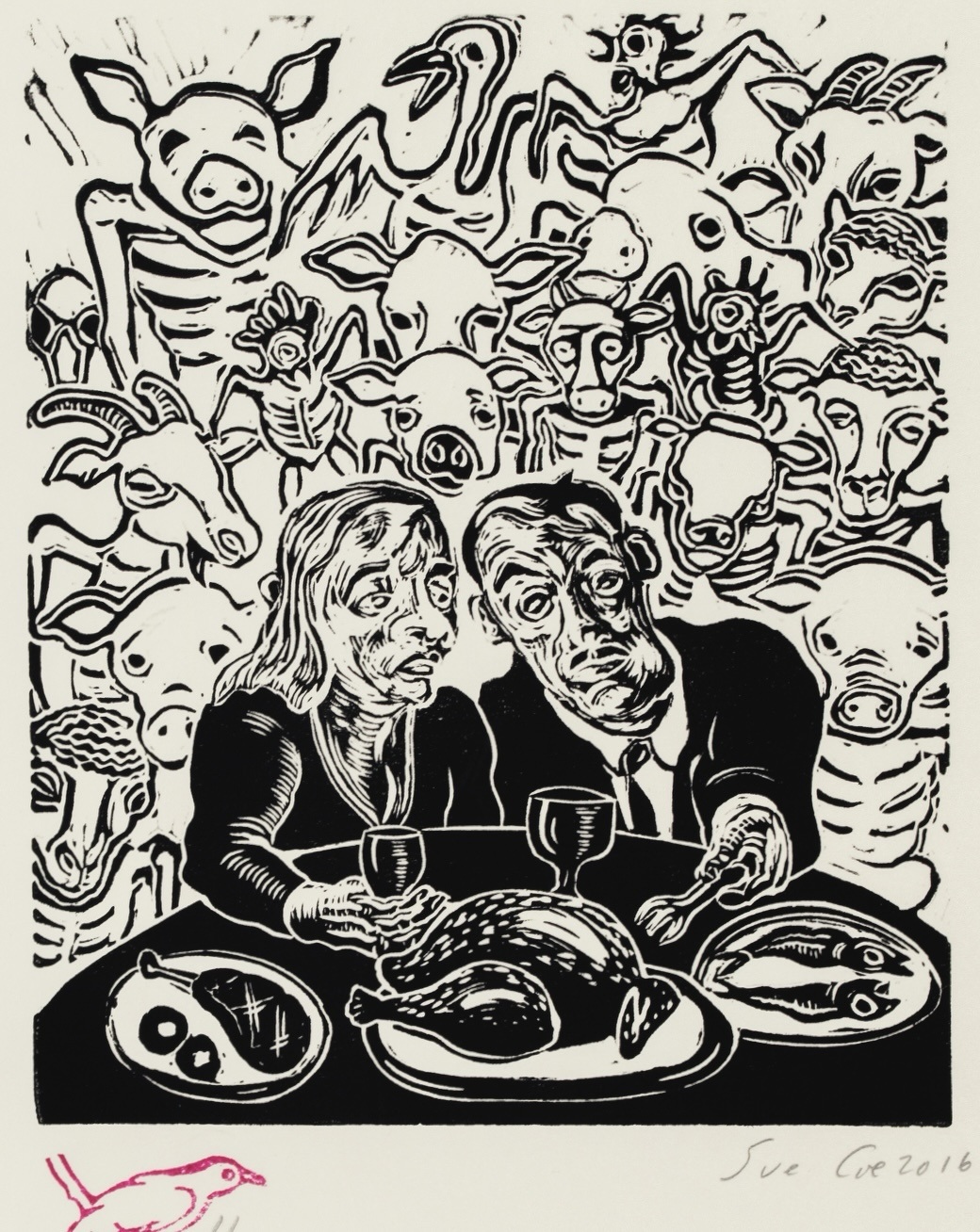

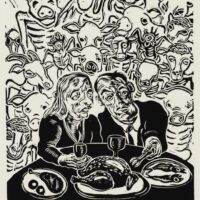

Sue Coe, Dinner for Two, 2016. Courtesy the artist.

Signs and wonders

The Norfolk landscape is mostly flat and unforested, but it boasts the Norfolk Broads,” 120 square miles of shallow lakes, marshes and canals. Now designated a National Park, the Broads is in fact man-made, the result of centuries of peat harvesting followed by centuries of flooding. Threatened bird and other animal species are found there, along with pleasure boaters, commercial fisherman, light industry, farming and housing. I sometimes hike there, with my wife Harriet, but find the terrain monotonous and the pleasure boats intrusive.

The rest of Norfolk is given over to agriculture, forestry, and industry as well as houses and flats for about 900,000 people. I live in the county’s biggest city, Norwich, just to the west of Broads National Park. It’s a city with about 140,000 residents. That’s small enough that I’ll sometimes bump into people I know from one place in another on the same day. For example, last week I saw Little Mike – the 6’3” son of Big Mike the greengrocer – outside the Book Hive on London Street, just a few hours after I bought from him some courgettes (zucchinis), aubergines (eggplants), swede (rutabagas), and rocket (arugula). I’m still learning British names for common fruits and vegetables. People here really do say “toMAHto” to my “toMAYto” just like the song, but “poTAHto” is considered too posh.

Compared to the U.S., the U.K. is severely nature-deprived. There is no such thing as a truly wild place here, David Attenborough’s recent TV series (Wild Isles) notwithstanding. I doubt there’s an acre that hasn’t at some point been harvested, grazed, mined, built over or plowed under. But contradictorily, there are probably few places in the world with more trails and footpaths and a more established tradition of “rambling” (short walks in the countryside) and “trekking” (longer hikes). This is a roundabout way of saying that Harriet and I take a lot of walks in the countryside – compromised as it is – and sometimes see real wonders: English oaks with trunks as wide as cars, kestrels hovering above marshes, and 800-year-old village churches with crenelated round towers and graveyards edged with yew trees. Lately, we’ve made note of more unwelcome signs – farm animals that are both victims of human cruelty and instruments of the countryside’s decline.

An upsetting ramble

A few days ago, we walked a four-mile loop from the small village of Itteringham to Mannington Hall (a moated, medieval manor) and back. There was a light rain, bracing wind and lots of mud, but we were rewarded by a footpath with a plank bridge over a tributary of the River Bure, that led into a forest with oaks, hornbeams and crab-apple. Despite Harriet’s warning, I took a big bite out of a plump, yellow apple that had fallen to the ground – my lips and mouth puckered as if I’d sucked a dozen lemons. At one point in our ramble, we left some woods and saw on our left a recently harvested field upon which a few dozen rooks were congregated. These birds are members of the corvid family, along with crows, jackdaws, ravens, magpies and jays, and are extremely smart and gregarious. Hearing their hectoring “caw caw” was like listening to a family argument.

Sows and farrowing arks, North Norfolk, September 2025. Photo: The author.

A little later, we saw a field of perhaps 500 acres populated with large, female pigs, each with a little, igloo-like plastic or tin hut, called a “farrowing ark.” Sows like these bear three-to five litters before being slaughtered, age about three. (A feral pig or boar can live 10-20 years.) Piglets are taken away from their mothers as soon as they are weaned at about four weeks, and sent to enclosed, “finishing” facilities to be fattened. Unsurprisingly, research indicates that sows demonstrate high levels of anxiety and stereotypical behavior (pacing back and forth, incessant chewing, etc) when their babies are removed. The little pigs are killed at five or six months, usually by carbon-dioxide poisoning. Moments after exposure to the gas, they gasp for breath and begin to thrash. CO2 forms an acid that burns the animals’ eyes, nostrils, mouths and lungs. Escape is impossible and death comes in a few minutes. Say what you will, comparison with Nazi gas chambers is inescapable.

A little later, we passed a herd of about a dozen tagged and castrated bulls in a small, fenced meadow. There was lots of grass, and they looked happy enough, but it’s hard to know. Cows are prey animals, so they don’t loudly complain when they are hurt or frightened. These bulls were young – not more than about 8 months; they’ll be slaughtered in a year or so. You probably don’t want to read about how they are killed, but if you do, click here.

We walked on, greeted some Blackfaced sheep munching short grass in a small pasture fenced in barbed wire, and then crossed a large field of sugar-beets, a major crop here. We turned left and continued alongside a hedge, dense with brambles (blackberries), stinging nettles and little else. These are eutrophic plants; they thrive on very high nutrient levels, common in landscapes polluted by animal waste and animal fertilizer. Pig (shit) slurry is sprayed on fields in Norfolk in Spring and Autumn. It’s not advisable to hike near a field that has recently been sprayed.

Passing over a stile, we entered a pretty meadow with woods on both sides. This time of year, there are few flowers, but we saw, here and there, surprising bursts of pink on tall green stems. I thought they were orchids, but Harriet knew better. They were Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera), an invasive plant – also eutrophic — that crowds out other flowering plants essential to native bees, butterflies, hoverflies, moths and wasps. They are seductive augurs of species loss and capitalist crisis.

“Late capitalism”

I’m generally disinclined to use the term “late-capitalism” because it assumes we are near enough the end that we can look back and chart capitalism’s full development. “Post-capitalism” is even worse; it suggests that the economic features that define capitalism – private ownership of essential industries, and production for the sake of profit – have been superseded. In fact, the pace of private ownership is accelerating not slowing, and nearly everything today — including the air we breathe – is priced and sold for a profit. The poor settle for cheap, polluted air while the rich can afford expensive, mountain or oceanfront air. The same is true for water and housing.

More than 70% of water resources in the U.K. are owned by private equity firms, pension funds, and other businesses headquartered in offshore tax havens. Water was privatized in the U.K. in1989 and has been a good business ever since. As we all learned in school, demand for water is inelastic – housing too. In the 1970s, a third of British families lived in public (“social”) housing; today, it’s half that number. A recent Labor Party initiative promises to reverse this, but the results are a long way off, if they arrive at all. Prime Minister Starmer would prefer to spend scarce money on armaments. Meanwhile, lords and ladies, financiers and lawyers, sports stars and tech entrepreneurs, live in stately manses in the Cotswolds and posh flats in Mayfair. They vacation in cliff-side villas on Lake Como or hideaways in the Maldives. They enjoy clean air and pure water and don’t care what it costs.

In the U.S., capitalism is faring no better, except for the very few. Life expectancy is falling, while poverty (especially child poverty) is rising. Economic inequality continues to accelerate and along with it anger among the majority that they lack even a crumb of what the rich possess in loaves: good homes, fulfilling work, satisfying food, affordable medical care, easeful retirement, and the expectation that their children will enjoy as good or better lives than they.

It wasn’t always thus. In its mid 20th Century golden age, capitalism created prosperity, though of course, more for some than others. Karl Marx foretold that success a century earlier. He was capitalism’s biggest fan as well as most clearsighted Casandra. The capitalist class, “the bourgeoisie,” he famously wrote in 1848 in The Communist Manifesto

“during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalization of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground – what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labor?”

Government investment during capitalism’s heyday enabled improvements in healthcare, transportation, communication, sanitation, fashion and entertainment. Growing profits and higher productivity led to rising living standards almost everywhere in the capitalist world. But there were also periodic crises that foretold a different eventuality: between 1914 and 1945, two world wars and a major depression; after that, regional wars, and multiple, short recessions. Then came the oil shock and stagflation of the 1970s followed by an economy characterized by boom and bust, succeeded by the Great Recession of 2007-9, when rising real estate prices and sub-prime loans led to bank failures, a stock market collapse, and the erasure of trillions of dollars of middle- and working-class wealth.

Today, despite the recovery of housing and stock market values, computerization, and the rise of AI, productivity is flat or in decline in most capitalist states. A glut of industrial capacity has led to de-industrialization (especially in the core capitalist nations), a rising service sector, and a mad search by the investor class for profits in financial services, crypto, precious metals, fossil fuels (despite everything), and pharmaceuticals (both licit and illicit). None of these have ensured stable growth or secured the lives of the mass of working people. Now, as in the 1930s, fascism has reared its head, like the Jack-in-the-box Mussolini in Peter Blume’s painting Eternal City (1937). Trump, just as authoritarians before him, prefers to blame liminal populations – in the present instance immigrants, trans people, and TV comedians — for the failures of the economic and social order he represents.

Capitalism’s greatest disfunction, however, isn’t its tendency to crisis or even its ultimate incapacity to deliver the goods; it’s the system’s inevitable slide to catastrophe, the consequence of its underlying premise that nature is an inexhaustible resource. The continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels, and ongoing despoliation of the environment, has led to a stage in capitalism that if not “late” or ‘post” is certainly “morbid.” Symptoms of capitalism’s ecological crisis are already apparent: communities destroyed by fire or flood; heat and smoke that make some summers in even temperate zones unbearable; and the growing insurance crisis. It isn’t the organized working-class, it turns out, that will be capitalism’s grave digger; it’s rising temperatures, depleted soils, hypoxic oceans, loss of freshwater resources, forest death, the extinction crisis, and the economic fallout from them all. “Hothouse Earth,” which is fast approaching, won’t be a welcoming place for anybody, MAGA or mogul. So, unless there is a sea-change is what Marx called the “metabolic interaction” between humans and the environment – that is, the achievement of a global “ecological civilization” – capitalism is scuppered. (My newest British locution.) What will follow is anyone’s guess.

“The omnivore’s deception”

A Norfolk ramble reveals nothing obviously apocalyptic. The landscape is distinguished by flat plains or gentle hills planted with cash crops, and populated by farrowing pigs, grazing cattle or sheep, many, many chickens, and less than a million people. There are marshes, canals, and broads as well as beaches, many of which are lovely and apparently unspoiled. But Norfolk, in its quiet way, is nevertheless what capitalist catastrophe looks like, and a lot of the reason is farm animals, or more accurately, human exploitation of farm animals.

Animal agriculture is a mainstay of the Norfolk economy. Though the county contains only about 1/70th the U.K. population, it produces ¼ of the pigs killed and the same percentage of chickens. The largest producer of pigs and chickens in the area is Cranswick plc, directed by Adam Couch. The business turns a profit of about $200 million per year and Mr. Couch rakes in a cool $5 million per annum in salary and other payments. (Most farmer salaries in the U.K. are between $50,000 and $100,000.) Cranswick routinely violates environmental laws – about twice a week for the past seven years – but that hasn’t stopped Couch from proposing to build a mega-farm for 750,000 chickens. The proposal was recently rejected by the King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council after 12,000 written objections, along with a petition with over 40,000 names. But that refusal won’t mitigate past and ongoing harms.

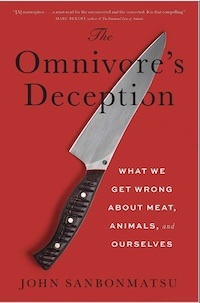

Meat consumption is marginally declining in the U.K., but exports to the EU and especially Asia are increasing. The same is true elsewhere, with rates of meat eating either level or slightly declining in North America, Europe and Australia, but rising elsewhere. The environmental consequences of the industry are dire. As the philosopher John Sanbonmatsu writes in The Omnivore’s Deception, “raising and killing animals for food is the single most ecologically destructive force on the planet.” Animal agriculture is responsible for a global cereal deficit and malnutrition, water shortages, deforestation, land degradation (including desertification), pollution, biodiversity loss and global warming. The next crisis of capitalism may reasonably be blamed on cows, pigs, and chickens — but it won’t really be their fault.

Sanbonmatsu’s book diagnoses a moral as much as an ecological crisis. Though animals suffer grievous harm by being corralled, branded, tagged, castrated, crated, shipped, prodded, stunned and killed, most people are blind to the violence. The popular image of cattle browsing lazily on the American plain, sheep grazing in British meadows, or chickens squawking in rural barnyards is grossly inaccurate and masks cruelty of an almost unimaginable scale. “Humans kill over 80,000,000,000 land animals and 3,000,000,000,000 marine animals every year,” Sonbanmatsu notes. Some 40% of the earth’s land surface is dedicated to animal agriculture, making it “the most extensive artifact ever built by homo sapiens.”

The ideological system supporting this apparatus is momentous in scale and insidious in effect. To diminish the natural empathy people feel for animals, and flatter our morbid appetites, the meat industry – composed of a few, giant, vertically integrated producers such as the Brazilian JBS and the American Tyson Foods — employ armies of marketers, salespeople, and lobbyists to persuade consumers that the products they sell are wholesome, healthy, fashionable, sustainable, and even kind. Supermarket retailers, the restaurant industry – especially the big chains, like McDonalds and KFC – advertisers and the media companies that profit from them, are all in on the conspiracy. So are universities with their “food science programs” funded by food and agrochemical conglomerates including Coca Cola and Bayer-Monsanto. And then there are the street-level meat pushers, including public intellectuals like Michael Pollan, Barabara Kingsolver, Temple Grandin and the late Anthony Bourdain.

The title of Sanbonmatsu’s book is derived from Pollan’s best-selling book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma (2006) which argued that decades of corporatization had created a meat industry that was dangerous, unhealthy and unsustainable, and that the solution was to support small, especially local farms, that raised humanely raised and if possible, organically fed animals. Vegans be damned, he suggested, conscientious Americans could have their meat and eat it too! The book was a smash hit and generated a library of imitators who lauded small farms, supposedly happy animals, and sometimes even artisanal slaughter. Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life (2007) similarly – and sanctimoniously –lauded small scale and do-it-yourself agriculture. Grandin was lauded for devising new ways to murder ever larger numbers of animals, supposedly without them knowing its coming. Bourdain earned fame and fortune for his publicized delight in killing and eating every imaginable part of an unprecedented range of creatures.

The problem with Pollan’s solutions to the food crisis, and those of his epigones, is that they are based on falsehoods. Small farms could never come close to satisfying the current American and global appetite for meat. In addition, there is no evidence that they are any kinder to animals than factory farms. Small scale and distributed operations are generally subject to less regulatory oversight than large, concentrated ones. (In most cases, they send their animals for slaughter to the same places as the big factory farms.) Small operations are also far more resource intensive. That’s the whole point of a factory!

Organic and “humane” meat are now mostly the product of large food conglomerates eager to cater to wealthy liberals wanting to eat the same way they always have but feel virtuous about it. Finally, locally produced food – whether animal or vegetable – is not necessarily less carbon intensive than foreign grown. Large shipments delivered great distances by ship often cost less energy per unit than small shipments sent short distances by truck. The issue is not the scale, location or operation of the industry; it’s the animal agriculture itself. There’s simply no good reason for eating meat except taste and custom – and those can quickly be changed.

Another walk in the country

The next time Harriet and I take a walk in the Norfolk countryside, we are going to conduct a thought experiment: Suppose the Norfolk County Council, supported by a new, Green Party majority in Westminster (led by eco-Populist Prime Minister Zack Polanski), undertook a program to transition farmers from animal to vegetable agriculture. Farmers were given financial incentives to make the change, towns and cities were encouraged to develop farmer’s markets, and consumers were given tax credits or vouchers to encourage more consumption of healthy grains, legumes, green vegetables, root crops, mushrooms and local as well as imported fruits.

And suppose there was also an initiative to reforest or re-wild the enormous amount of land that was freed up by the transition from growing feed for animals to food for people. Beyond that, imagine native grazing animals and predators – long extirpated in the U.K. – brought back to Norfolk to help restore ecological balance. Additionally, there’s an effort to remediate polluted lakes and streams and create conditions for the revival of threatened fish, amphibians and crustaceans.

Imagine that invasive plants in moors, grasslands and wetlands are removed by legions of people – young and old – many from blighted cities and towns. (They are hired at good wages and taught lessons in botany, horticulture and ecology.) Native plants are re-established to foster a diverse and growing population of bees, wasps, butterflies, dragonflies and other insects. Birds long since absent from the British Isles, or very rare, such as the Golden Eagle and Dalmatian Pelican are reintroduced, along with endangered mammals such as the pine marten, red squirrel, water vole and Scottish wildcat.

As Harriet and I cross a field littered with kernels of grain left from a recent harvest, we imagine seeing, among the dozens of browsing rooks, some wary harvest mice, voles and hedgehogs. Circling above are bearded vultures and in the distance, a marsh harrier. Re-entering the woods, we cross a fresh, clean stream and pass into a wet, flowery meadow with cowslips, cornflowers, oxeye daisies, and marsh marigolds – not a Himalayan balsam in sight. Continuing on the well-marked trail, we see on our left, a forest edged with young oaks, birches and hornbeams, along with a few mature crab apple trees laden with ripe yellow orbs. I approach one tree, not this time, to taste the sour fruit, but just admire its abundance. To our right, is a 500-acre field with hundreds of newly planted trees – mostly wild privet, common beech and field elm. Interspersed among them are soft-field ferns, lily of the valley, wild garlic, foxglove and meadow cranesbill. But prominent among all this bounty – because it is human made – is a bronze marker, about four-foot tall by three-feet wide, planted upright in the ground. It resembles in size and shape the tombstones we saw in the churchyard we passed, the one bordered with yew trees. On its surface is the profile effigy of a sow with distended teats and below it, the following words:

“On this field, circa 2000-2025, some 300,000 piglets were born of 30,000 sows. All were killed to slake human appetites and gratify human hubris. What remains of them are only the faint echoes of their squeals and outcries. If you stand here quietly and close your eyes, you may hear them.”

We shut our eyes and do.

The post Morbid Appetites of Late Capitalism appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed