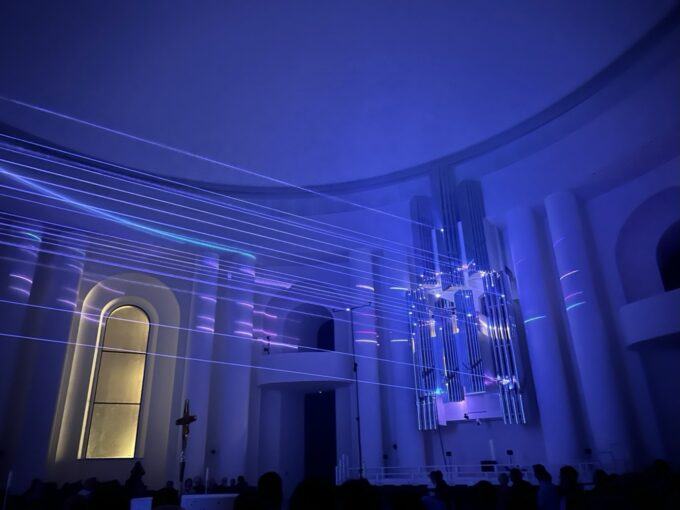

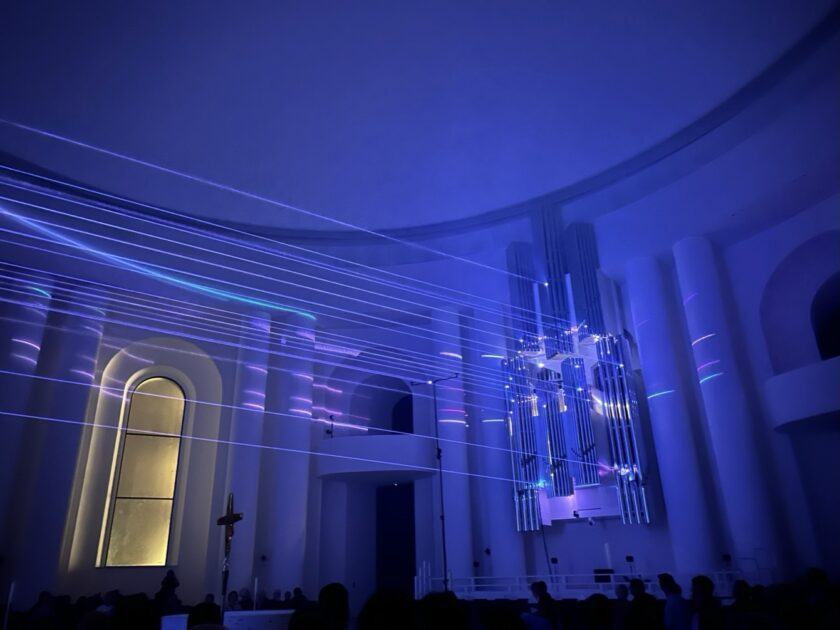

Close Encounters of the King Kind: the Aggregate Organ Festival, Berlin. Photo: David Yearsley.

Movie screenings here start with short commercials: zany, wink-wink spots showing more than a little sun and skin to whet the appetite for ice cream and beer and cars and beach vacations. In contrast to the teetotal multiplexes of the American Homeland, Old Country theaters sell alcoholic drinks at the concession stand.

Nowadays, not just consumer goods but also cultural events are pitched before the feature film begins in Berlin cinemas, especially in those run by the resourceful Yorck Kino group with its groovy theaters spread across the sprawling city. The advertised offerings include music festivals, concerts, operas, ballets, art exhibitions in major museums, jazz and rock shows. After these astounding riches are teased, come the trailers for upcoming movies.

It’s not just in the previews before highbrow independent films that Berlin is lauded as a major cultural capital. You get to ogle these artsy wares before Hollywood imports like the current Olivia Coleman-Benedict Cumberbatch vehicle, The Roses, in which Cornwall in the Southwest of England is made to play the rugged Mendocino Coast and does about as good a job of it is as do the acid-tongued expats of teaching the locals the nuances of intermarital verbal abuse. That’s the main gag of this remake that throws a pair of nasty-cat Brits at each other and among the gormless Yankee pigeons.

Yet unlike the original (War of the Roses, 1989), the remake chooses California light (make that “lite”) over unalloyed ill-will. The outbreaks of sentimentality in The Roses can be measured by that infallible gauge and accomplice of movie emotion—the soundtrack. Maudlin string strains offer their oozy compliance for the rare, but no less trying moments of grace and goodwill wedged in between the barbs and blows. These fleeting glimpses of humanity are meant to convince us that the warring top-chef wife (Coleman) has goodness somewhere among her non-locally sourced ingredients. The embittered architect of a husband (Cumberbatch) designs an oceanside edifice which, along with his reputation and ego, is demolished by extreme weather. It is he, then, who is prescribed the main doses of soppy sonic therapy, as when he swerves off-piste and off-plot and saves a beached whale. As the bantam CGI leviathan swims off into the surf, hubbie’s good deed drifts on a harmonic bed of synthesizer kelp, whispering from the waves of hope and fulfilment and alerting us to the dubious fact that deep down, far below the savage whitecaps, he really is a good person.

Better to be bad.

In such moments when music is disastrously forced to redeem what should be an unredeemably black comedy, one has to remember that the cinema has always been a light and sound show, even when it was an organ that underscored the action and amplified the emotion up on the mute screen. Although one thinks of an organ’s façade—often as big or bigger than the big screen—as grandly impassive, the King of Instruments has always provided a feast not just for the ears but also for the eyes.

Many organs were engineered to have moving parts that entertained the sight—from King David playing his harp to singing saints whose pious countenances were often flatteringly modelled on faces of the expensive instrument’s wealthy donors.

No multi-media entertainment center of the early modern period was more spectacular than the gift Queen Elizabeth sent from London to Sultan Mehmet III in Istanbul in 1599. Built by the fearless innovator Thomas Dallam and transported to the Ottoman capital by sea, then reassembled by him in the potentate’s palace on the Bosphorus, this blockbuster import boasted the Top Gun technology of its time, as is clear from the following lines excerpted from Dallam’s own epic—and orthographically diverse—account:

Firste the clocke strouke 22; than the chime of 16 bells went of, and played a songe of 4 partes. That beinge done, tow personagis which stood upon to corners of the seconde storie, houlding tow silver trumpetes in there handes, did lifte them to theire heads, and sounded a tantara. Than the muzicke went of, and the orgon played a songe of 5 partes … Divers other motions thare was which the Grand Sinyor wondered at.

90 Years before Dallam’s organ embassy across the Christian-Muslim divide, the German master organist Arnold Schlick, a celebrated virtuoso of European standing, published history’s first book on organ building and playing: Der Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten.

In this seminal treatise, Schlick agreed that the organ was “mainly to be heard,” but he also emphasized its vital visual qualities. These decorations should inspire proper devotion and not present carnivalesque freak shows in God’s house. Accordingly, he lambasted a nearby organ that featured

a monk that lunged out of a window as far as its waist then snapped back in again. This often shocked young and old, men and women, so that some were excited to swear and others to laugh. This should properly be avoided in church, especially by the clergy. Likewise, the grotesque faces with wide mouths that open and shut, and long beards, and complete figures that strike about, encourage improper manners. Also, rotating stars with little bells that ring, and other such things, do not belong in church. When our Lord God holds a church fair, the devil sets up his stall next to it.

Schlick was blind. Maybe this stoked the vehemence of his disapproval, miffed as he may have been at missing out on the slapstick fun of these automated religious revues.

Schlick would also have missed—and vociferously maligned—the laser show and play of shadows that diabolically silhouetted the organists at the console at the closing concert of this year’s “Aggregate Festival: New Works for Pipe Organs” in Berlin. It hadn’t been advertised before The Roses the night before, but the word had gotten out: the Sunday night concert was fascinating and mysterious and extremely well-attended.

The event took place in St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, whose plump green dome and pillared portico stand guard at the southeast corner of the Bebelplatz in the center of Berlin. It was on this square in the spring of 1933 that Nazi students pillaged some 20,000 “un-German” books from the adjacent Humboldt University Library and burned them in a massive bonfire. A small window cut into the ground in the middle of the cobblestone expanse commemorates that crime, but is only apparent when you come near and stand over it and look down into the empty subterranean room below: a library with nothing on its shelves. Invisible from afar, untouchable from above, this underground, understated monument both captures and conveys its own absence. There is literally nothing to see or to read.

Built in the middle of the 18th century, St. Hedwig’s Cathedral is decidedly above ground—still. Badly bombed in World War II, its interior was reconstructed a decade later in austere modernist style. A re-renovation begun in 2018 was completed last year. The church’s latest architectural incarnation stripped the interior of all remaining ornament and painted the walls, denuded columns, and underside of the dome a white so blinding that priests would be advised to don welding glasses when celebrating the Mass if they don’t want to go blind like Schlick.

On the way into the concert on that September sabbath night, I didn’t receive a ticket. Instead, I got a stamp on my hand as if this were a rock concert or a carnival. Maybe some in the audience had plans to duck out to the square for a cannabis vape session during the show. There would have been plenty of time for it, as the concert would push on without intermission for two hours.

Before taking my seat in the circular space, I picked up some brochures at the table near the entrance advertising other organ events in the city. Alongside this info was a stack of playing card-sized photos of what looked like Lee Iacocca. The former CEO of Ford and then Chrysler died last year, and if anyone is due for canonization, it is Iacocca — St. Lee, the worker of the Mustang and Minivan miracles. Colorful frescoes surrounding his goodly visage with these auto relics would certainly have livened up St. Hedwig’s. Martyred by Henry Ford III, even though he made the company billions, would-be St. Lee will have to wait a few more decades before working his way back up the corporate ladder beyond the Pearly Gates.

I flipped over the collectible card to find out it was of Pope Leo. That explained the pontifical white and tasteful splash of racing-strip red laid over the shoulders.

Stark in line and angle but still the most decorative feature in the relentlessly sober St. Hedwig’s interior, the modern organ juts out from its balcony set directly between the two large entrance doors.

When the lights dimmed for Aggregate showtime, the white walls glowed, the metal pipes glimmered.

Avowedly avant-garde music began to echo around the reverberant half-sphere of ecclesiastical space. In the first two of the three forty-minute pieces, the discourse alternated between demonic harmonies and heavenly cumulus puffs on which floated languid, unformed melodies.

The second of these explorations was for an organist up in the loft and two laser players at their controls on the far side of the sanctuary. At the organ console, the conflict between Good and Evil, concord and discord, raged on as the laser beams poked and slashed at the pipes like picadors at a bull fight, goading the holy beast into unholy war. The sharp, colored beams of the laser were encased in a broad shaft of more diffuse light, infiltrated by billows of steam. This odorless vapor never made it all the way over to the organ, as if the blasts from the pipes held the infernal clouds at bay. The Catholic olfactory menu was not being served that Sunday night. There was no thurible of incense to the famished sense of smell. I began to wish that the vaping would happen inside.

The light show played off the scarily fascist white columns ringing the church’s interior and intersected with the sonic artillery of the cannon-shaped organ pipes. That this spectacle was taking place, even spilling out onto the Bebelplatz, made me think of Nazi architect Albert Speer’s cathedrals of light at the party rallies in Nuremberg. History in Berlin has a way, like smoke, of insinuating itself into everything.

The last of the evening’s three works abandoned antagonistic aesthetics. The demons of disorder had hoisted up the white flag, though only metaphorically: if there had been a real sign of surrender, it would have been invisible against the everywhere whiteness. Pure and absolute was the elongated stasis in C. Linus Pauling would have been in heaven. Every so often another organ stop was pulled out or another note depressed. Ten minutes in, a G joined the sonority. Sometime later, an E completed the triad, often allegorized by the music theorists of yore as an embodiment of the Trinity. Religious symbolism could not help but intrude on these dark rituals conducted within whitewashed sacred walls.

Schlick would have been glad to hear that the lasers had been retired. Pope Leo would have been happy that Good had won out over Evil in the end. But once again, Bad would have been Better.

The post Sight and Sound in Berlin: Saturday at the Movies, Sunday in the Church appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed