Photo: Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times/Redux

Photo: Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times/Redux

The criminal indictment against former FBI director James Comey will be parsed on the law, the facts, and the question of whether the Trump administration’s decision to indict a person on Donald Trump’s enemies’ list in the first place amounted to a vindictive and selective prosecution. All of those analyses have their place, and Comey has already indicated that he has “great confidence in the federal judicial system” such that he is willing to proceed with a public trial to clear his name.

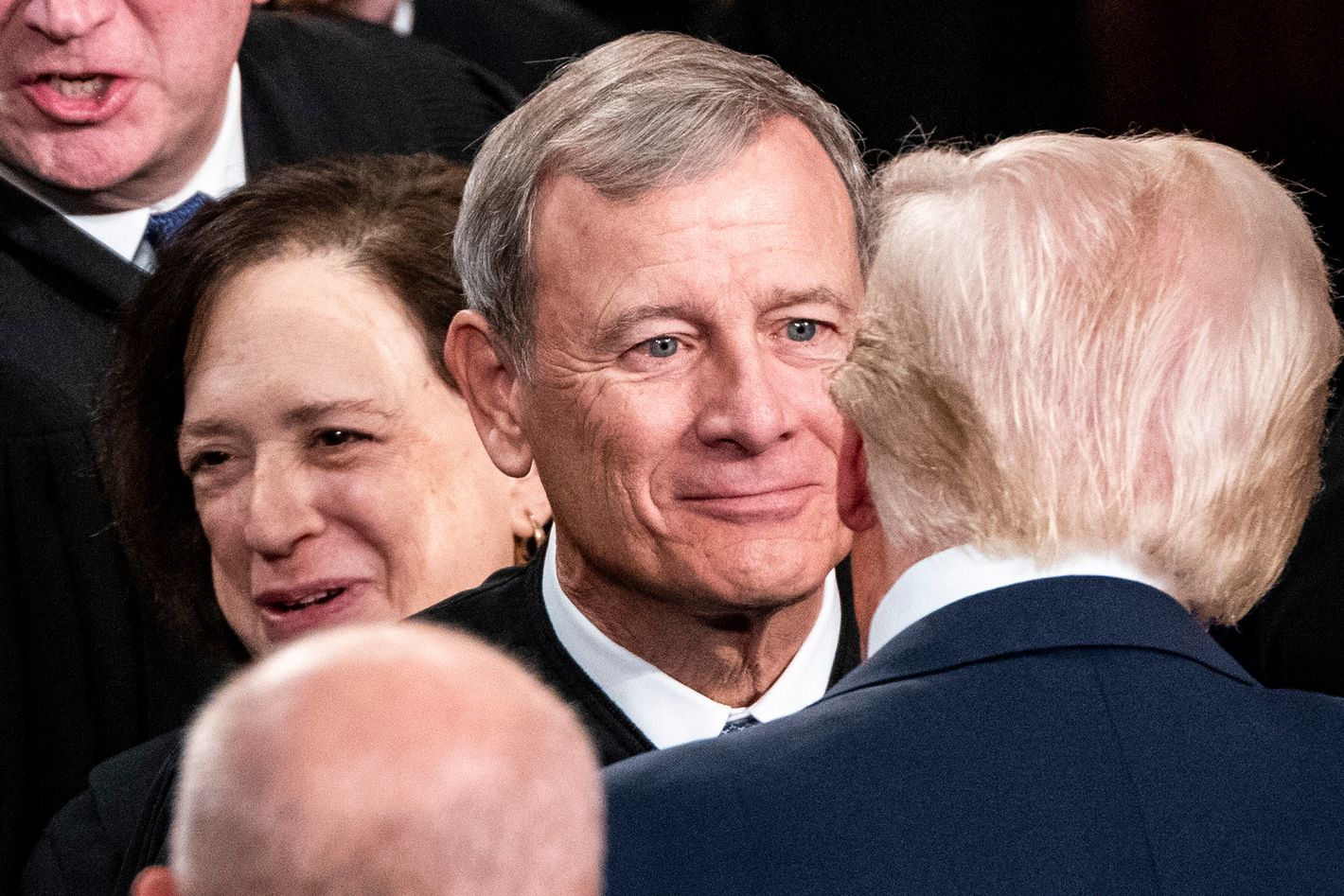

Yet the reason he finds himself in the president’s crosshairs, apart from the subservience of a newly appointed U.S. attorney in Virginia with no experience in criminal law, and an attorney general who can’t even bring herself to refer to Comey by name on the day of his indictment, can be traced to the federal judicial system itself. It is the Supreme Court of the United States, led by a chief justice who has done more than most to empower a presidency unbound by law, that is responsible for giving Trump the unlimited freedom to lean on the Justice Department to prosecute anyone he wants, even when the only evidence to predicate those investigations and prosecutions is the president’s feelings and not much else.

Yesterday was James Comey’s turn. Tomorrow may be Letitia James. Kilmar Ábrego García, though not formally a public enemy of the president, is now the subject of a political prosecution where the White House, the Justice Department, and the Department of Homeland Security are all acting in concert to demonize, criminalize, and ultimately deport him to a country not his own.

In all of these cases, sooner or later, the Trump administration can be expected to seek refuge in the work of Chief Justice John Roberts, whose maximalist language in Trump v. United Statesnot only granted Trump a shield from criminal investigation and prosecution, but also handed him a sword to order criminal investigations and prosecutions—even sham ones. The so-called immunity decision, in which Roberts led his conservative supermajority to endow Trump with broad immunity over his official acts leading up to the insurrection at the Capitol, is about far more than presidential impunity over a failed plot to remain in power. The ruling, in ways that are irrelevant to its bottom line, contains breathtaking language that categorically places the president in direct control of the attorney general, her Justice Department, and any other federal prosecutor down the chain of command.

Re-reading the decision, which was supposed to be fashioned as “a rule for the ages,” shows how ill-considered the rule was to start. In the part of the decree where Roberts analyzes special counsel Jack Smith’s indictment accusing Trump of subverting “the Justice Department’s power and authority to convince certain States” to engage in a fake electors scheme—by all accounts, an illegitimate use of the department’s functions—the chief justice spends little time in the scheme itself. (As a result, Smith was forced to drop these allegations from his case.) Instead, he offers a rose-colored view of a president’s authority over the Executive branch, how he “may discuss potential investigations and prosecutions with his Attorney General and other Justice Department officials,” and how even threatening to fire an acting attorney general for diobeying unlawful orders falls within the “conclusive and preclusive” authority of the nation’s chief executive. That is, neither courts nor Congress may second guess any of these actions with proceedings or laws authorizing a criminal prosecution.

Not even investigations that are considered a “sham,” Roberts writes, “divest the President of exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials.” As a result, he adds, “the President cannot be prosecuted for conduct within his exclusive constitutional authority.”

Absolute immunity over that course of conduct is bad enough. Yet the Trump administration, at this very moment, is running with this and related language in Roberts’ opinion to justify other presidential overreach in the lower courts and before the Supreme Court itself. The highest-profile example is ripe for a decision: Any moment now, the justices are expected to rule on an emergency request from the Justice Department to green-light the president’s chaotic and pretextual attempt to fire Lisa Cook from the board of governors of the Federal Reserve—the first such attempt to fire a sitting governor in the board’s 111-year history. A who’s who of former Federal Reserve members, Treasury secretaries, economic advisers, and other high-ranking Republican appointees have warned the Supreme Court not to play ball—unless the justices want to invite chaos and destabilize the nation’s economy and people’s retirement portfolios.

Solicitor General D. John Sauer—as it happens, the former personal lawyer who argued and won the immunity case last year—leans hard on the ruling he helped generate, and he does so in a way that would shut the door to any judge ever scrutinizing a president’s firing decision. According to Trump v. United States, he writes, Article II of the Constitution “creates ‘an energetic, independent Executive’”—not a president who is “subservient” or who “must follow judicially invented procedures even when exercising core executive power.” Again quoting from the Roberts opinion, Sauer adds that a “president’s removal power is ‘conclusive and preclusive,’ meaning that exercises of that power ‘may not be regulated by Congress or reviewed by the courts.’”

Then comes this kicker, entirely lifted from the immunity decision: “Any inquiry ‘into the President’s motives’ ‘would risk exposing’ the President’s actions ‘to judicial examination on the mere allegation of improper purpose’—an outcome that would ‘seriously cripple the proper and effective administration of public affairs.’”

Which is Sauer’s lawyerly way of saying: Thank you, John Roberts. Your own lofty vision of presidential authority prevents the judicial branch from even second-guessing a president ordering the Justice Department to prosecute a former FBI director, simply because he can. Under this vision, judges cannot assess the legality of firing a high-ranking official whom the law insulates from being dismissed on a whim, or as a result of a questionable criminal referral from a loyalist. And there’s no judicial recourse against the president if the Justice Department decides, as reported on Thursday, to deputize more than a half dozen U.S. attorney’s offices to investigate and possibly charge the George Soros-funded Open Society Foundations. And other than fighting the charges in court, the same goes for the as-yet-uncharged Letitia James.

The list of culprits for destroying the Justice Department and the politically driven prosecutions of the second Trump administration must include John Roberts, their chief enabler. And unless and until the Supreme Court reverses the damage done, the judiciary that Comey believes in will have to work hard to abide by the law as it stands—going through the motions of an arraignment, a trial, appeals, and other proceedings that should’ve never been set in motion. Worse still, judges will have to pretend this abuse of official power, which we’re told the Constitution doesn’t allow them to question, is nothing more than a president taking care that the laws are being faithfully executed.

More on the Comey indictment

Trump Justice Department Indicts James Comey: Reactions and AnalysisThe Meaning of the Comey IndictmentJames Comey Under Investigation for Seashell ‘Threat’ to Trump

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed