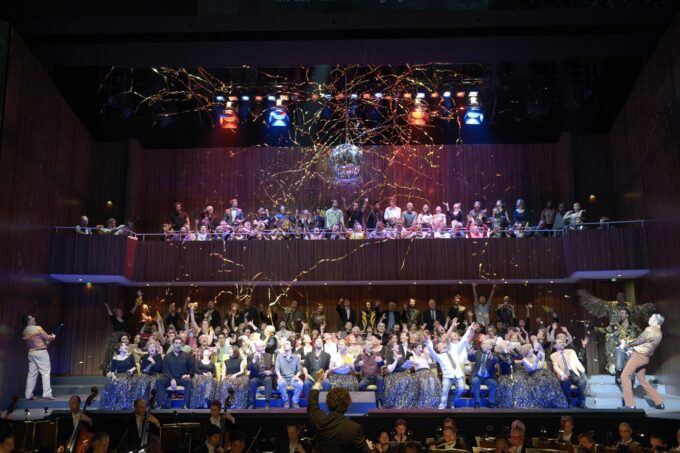

Who’s watching who? The onstage chorus/audience for Rigoletto at the Deutsche Oper, Berlin. Photo: Bettina Stoess.

Opera thrives on competition as much as collaboration—on who can sing higher, louder, longer, more passionately; what production can seduce or scandalize most abundantly; which company can hoard the most prestige while staving off bankruptcy the longest.

Sung drama was born as a regal pursuit in Italy around 1600, but was soon taken up by northern European monarchs and cities eager not just for the entertainment but also the glamor they brought.

These days, Berlin has three major opera houses of international standing. That’s an impressive cultural density for a city with a population just under 4 million. Although the three companies operate under the financial management of a single foundation, comparisons between them and perhaps also rivalries are inevitable, especially during times like the present, when funding belts are being tightened around their substantial operatic girths.

The Deutsche Oper in the western borough of Charlottenburg was founded in 1912 when the district was an independent city, the richest in all of Prussia. That lofty status demanded an opera house to compete with neighboring Berlin’s, which had been founded by Frederick the Great in 1740 and stood in the city center just across the Spree River from the Royal Palace.

These two opera houses were—and still are—just four miles distant from one another along Berlin’s main east-west boulevard, which begins under the name of Unter den Linden in front of the downtown Staatsoper (the State Opera; formerly the Court Opera) and a while after running the Brandenburg Gate changes its name to Bismarckstraße in honor of the German Empire’s first Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. The Iron Chancellor preferred house concerts to opera houses.

When the Nazis took over, Joseph Goebbels became head of the Deutsche Opera and Hermann Göring was installed atop the Staatsoper Unter den Linden. Such seizures of cultural power are now familiar to Americans since Donald Trump’s “election” as chairman of the board of the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, earlier this year. Not surprisingly, the German opera in Berlin-Charlottenburg became, along with the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth, the essential operatic stage for the Nazi regime.

Both Berlin opera houses were badly bombed during the war. The East Berliners reconstructed theirs, whereas the West Berliners tore theirs down and replaced the original neoclassical colossus with a modernist box. There’s not a column or pediment to be seen, just big square windows on the sides and a massive pebble-studded wall with block capitals reading DEUTSCHE OPER BERLIN facing onto Bismarckstraße. Bookending the foyer’s mezzanine level are two very cool boxy bars.

I love the place not just for the décor but even for its penchant for risk. The first opera I saw here was the notorious 2003 staging of Mozart’s Idomeneo directed by Hans Neuenfel, then the baddest of bad boys of German Regietheater—this so-called “Director’s Theater” marked by often outlandish interventions in the original texts: alternate beginnings, middles, and/or endings; diverse acts of gratuitous sex and violence; and a commitment to offending strict constructionists and other traditionalist as often and as aggressively as possible. Neuenfels certainly achieved those goals at the close of his Idomeneo by parading the severed heads of Buddha, Jesus, and Mohammed on spikes (spoiler alert: none of these prophets appear in Mozart’s original) to a hailstorm of Pfuis and Boos from the auditorium. Fearful of retaliation from Islamist extremists, the Deutsche Oper cancelled the production but then regathered its courage and resolutely brought it back, now with metal detectors at the entrance heightening both security and dramatic intensity. This season, an exhibition dedicated to “Skandal!” can be surveyed in the foyer.

The house Unter den Linden got a redo to the tune—make that, mighty chorus— of 400 million Euros, the final tally on the reopening in 2017 reflecting massive cost overruns. The Deutsche Oper was dedicated back in 1961 and asking for 20 million for its own makeover—operatic pocket change.

As these radically different sums suggest, since the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the Staatsoper garners more prestige and public money than its Charlottenburg counterpart. Over the last decade, ticket sales at the Staatsoper have been more robust than those at its Charlottenburg counterpart, which is, on average, one-third empty.

I’d say that at last Friday’s musically powerful, theatrically unfocused but still enthralling performance of Verdi’s Rigoletto, a bit more than half of the seats were taken. Frederick the Great’s solution to flagging audiences of the 1770s, his capital city impoverished by a succession of wars that he had started, was to command his royal regiments to fill the place up. I wouldn’t be surprised if Trump soon deploys the National Guard in like fashion as indifference and even disgust build for his “pro-faith” and “pro-family” menu at the Kennedy Center.

What the Charlottenburg public lacked in numbers last Friday, it made up for in enthusiasm. A dozen rows back from the orchestra pit, we sat among a group of partisans—many of them probably family relations—of the young and dynamic conductor Daniele Squeo, an Italian who studied in Germany. Right from the start of the overture, with its portentous brass maledictions troubled by timpani and throttled by string tremolos surging up to quaking tutti chords, Squeo led the virtuosic Deutsche Oper orchestra with accuracy and flexibility, fire and feeling. When the conductor joined the cast in the long series of bows—not curtain calls, since there was no curtain—his supporters Bravo-ed, clapped and stamped more loudly than ten of the aforementioned timpani. A particularly exuberant man next to my daughter whistled so loudly that he inflicted what she was sure was permanent hearing loss on her left ear, prompting her to enjoin me to make the following plea to the Deutsche Oper: Please, please add a “no whistling” clause to the opening public announcement asking cellphones to be turned off and forbidding photography and recording during the performance.

The Italian faithful also raised an exalting sforzando to soprano Nina Solodovnikova. She sang the role of the ill-fated Gilda with intimate nuance, surety and emotional reach that made you almost believe this opera’s outlandish and deeply misogynistic proposition that her character would give her life for the bluff Duke of Mantua even after she’d learned that his declarations of love were all opportunistic lies. That bel canto cad was sung with barrel-chested bravura and unwavering cynicism by tenor Andrei Danilov. (Presumably, both Solodovnikova and Danilov have publicly repudiated Putin and his Ukraine War in order to be allowed to appear on the Deutsche Oper stage.)

As Gilda goes to her death, the reprise of the work’s most famous aria—indeed one of the most famous in all of opera— “La donna é mobile” rang out from off-stage in Danilov’s haughty, heart-piercing tones, not as a triumph of manly prowess but as a self-inflicted critique of opera’s mechanisms of predation.

Our nearby Italian cohort also raised the roof—flat, as any modernist structure worth its concrete must be—for the Spanish-American baritone, Daniel Luis de Vicente, whose rich, sometimes grainy, often restive and always resonant baritone whipsawed between rage and pathos. His was a devastating embodiment of a best-intentioned paternalism that fatally confuses overweening control for honest love. This Rigoletto didn’t need the hunchback—the traditional stigma of this pitiable, and pitiless jester but, like blackface for Verdi’s Otello, is banned from the modern opera stage—to elicit both loathing and compassion.

Berliner Jan Bosse directed the production, with the sets by Stéphane Laimé. The theatrics began even before the overture, with the chorus already arrayed on stage in raked seating that meticulously mirrored the real auditorium on the other side of the pit. The seats, handrails and even the 1960s veneer of dark wavy grain on the walls had all been mimicked in the service of the by now hardly original gag of holding up a mirror to the audience.

These chorus-members-as-operagoers fiddled with their phones, flirted, dozed, thumbed through their program books, and sipped at champagne. Just before Squeo made his way to the podium, a latecomer rushed onto the stage from the wings to fight past a dozen disapproving knees on the way to his seat.

When Rigoletto joined the party on stage after the music had at last begun, he was costumed as a humpless glitter-bunny. The Duke wore cowboy boots and a western shirt and mirrored sunglasses. The professional hitman Sparafucile (Tobias Kehrer) was a blinged-out, tattoo-scarred, hoodied thug, whose cavernous baritone would have echoed its dark menace as fatefully had he been wearing a pink tutu and ballet slippers, rather than biker pants and combat boots.

But the stage-on-the-stage gimmick remained just that. It never yielded insight, contradiction, or even a whiff of useful alienation. By the time the evening had reached the final scene, where Rigoletto opens the body bag and discovers his own daughter lying dead before him, killed by the hitman he had hired to murder Gilda’s seducer, the on-stage seating had already been elevatored away. At last, the drama came into minimalist, moving relief. I’d been expecting Bosse to have the meta-audience stay on either to drool over the melodrama’s grizzly crux or maybe just plain ignore it while gorging TikToks on their phones.

Two-and-a-half hours earlier, as I had stood at the end of our aisle waiting to take my seat before the performance began, two elderly women, surely long-time season-ticket holders, came through the doorway to our section. As soon they caught sight of the setand the chorus/audience looking directly back at them from the stage, one of the ladies snorted contemptuously and said loudly: “Schon wieder blödes Regietheater!” — Damn Director’s Theater again! Probably the pair had been at Neuenfel’s Idomeneo twenty years ago, so they couldn’t have been that surprised at what they saw. Their disapproval was probably just ritual venting.

Still, I tried to reassure them: “You can always just close your eyes.”

Next Week: the third and youngest of Berlin’s opera houses puts on Jesus Christ Superstar at the Nazi Airport.

The post L’Opera è Mobile: Rigoletto in Berlin appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed