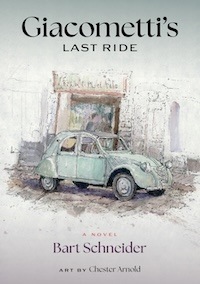

Giacometti’s Last Ride: A Novel by Bart Schneider; Art by Chester Arnold; Kelly’s Cove Press; 2025; $20.

Artists, Ezra Pound once observed, were “the antennae” of the human race and provided a “warning system” about the future. They have also been keen observers of the present and have described the world without embellishments. In Giacometti’s Last Ride, novelist Bart Schneider and painter Chester Arnold, offer a stunning bookend to James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, a literary masterpiece which was just what I wanted and needed as a 19-year-old student eager to become an artist.

In Cormack McCarthy’s western and the film based on it, the Texas/Mexico border is “no country for old men.” The opposite is true for Giacometti’s Last Ride. The novel that Schneider and Arnold have assembled with words and images explores a country of old men, white and European, that provides a model for growing old with dignity.

They have also unromantically mapped a crowded corner of the 20th-century art world that transformed ways of seeing and thinking. Schneider and Arnold surround Giacometti with a cast of aging painters, sculptors, writers and photographers who are beyond their prime. They live and work in Paris and they’re mostly harmonious with one another, though the Picasso who emerges in these pages tends to be competitive with his peers.

In addition to Giacometti and Picasso, the cast includes Giacometti’s brother, Diego, and their contemporaries: Samuel Beckett, known here as “Sam”; and Eli Lotar, a photographer who explains that Giacometti’s work represents  “man’s isolation.” Lotar adds that Giacometti’s tall, thin, dramatic figures—which are less than three-inches in height—had a “particular poignancy after the tragedy of the war when so many people wandered through the world lost.” Giacometti’s art reflects the anxieties of the age in which it was born.

“man’s isolation.” Lotar adds that Giacometti’s tall, thin, dramatic figures—which are less than three-inches in height—had a “particular poignancy after the tragedy of the war when so many people wandered through the world lost.” Giacometti’s art reflects the anxieties of the age in which it was born.

As readers of modern literature know, James Joyce offered the quintessential account of the alienated, anxious modern writer in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, published at the start of WWI and a classic ever since then. Joyce’s Irish-born protagonist, Stephen Daedalus, observes famously, “The only arms I allow myself to use, silence, exile, and cunning. ” The Giacometti who takes his last ride in these pages is far less defiant, though no less experimental than Joyce or his hero and no less dedicated to the demands of art.

Born in Switzerland in 1901 and influenced by the surrealists and the cubists, Giacometti settled in Paris in 1922. He created some of his best known work, including Grande femme debout I through IV, in the early 1960s. Grande Femme Debout 1 sold for $14.3 million and Pointing Man for $126 million. Giacometti died in Switzerland in 1966 two decades after the end of WWII when young white male artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning came to the attention of the world.

Giacometti turned to figurative painting in the mid-1950s. His success, which often overshadowed women artists like Helen Frankenthaler, was due in part to the myth that New York not Paris was at the center of the art world. Bye bye Left Bank studios, hello Greenwich Village galleries.

French author, Serge Guilbaut, tells much of that story, which never seems to get old, in his book, How New York Stole the idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War. After 1945 and well into the post-war era, New York art critics persuaded consumers to shell out big bucks, buy works of abstract expressionism and display them on the walls of their homes and apartments. As Schneider knows and shows in his new novel, Giacometti’s career benefitted from the notion that New York replaced Paris as the beating heart of the art world.

In Last Ride, the artist himself explains to a Parisian hoodlum how the New York art world operates. “It doesn’t matter if it’s good or not,” Giacometti says. “The fact that I painted it makes it important and valuable.” He adds, “I think it’s absurd but that’s how the art world is.” To sell art in New York, he must sell himself and his personality which becomes increasingly challenging as he ages.

Giacometti asks the hoodlum, who seems to have stepped directly from the celluloid world of film noir, “Why not become a collector?” He adds, ‘”Once you’re a collector, your status rises in the world,” and you “gain access to a wealthy echelon.” The acquisition of art can turn the criminal who plays his cards right into an accepted member of bourgeois society.

How much of the story that Schneider tells is based on fact and how much is based on fiction , the author doesn’t say. There are no acknowledgments to any of the biographies, including Giacometti: A Life (1997) by James Lord, who knew the artist and his entourage intimately well. Still, Schneider allows that he has ”fabricated some events, minor characters and the dialogue.” Which ones, a reader would like to know. Did his wife, Annette, and his lover, Caroline, really spat like two cats, or was that fabricated?

In a note at the back of the book, Chester Arnold writes that the “masterworks” by Giacometti and his contemporaries “provided inspiration for any child born in the mid-twentieth century with ambitions to be an artist.” He includes himself as one of those ambitious kids. Arnold adds that the great artists were as “recognizable in their persons as in their creations.” That was certainly true of Picasso who turned himself into an iconic figure, albeit less true for Giacometti.

Four women join the cast of the novel’s indelible characters: Giacometti’s wife, Annette, who begins her life as a member of the Swiss bourgeoisie and who is eager to become a bohemian; Caroline, a sex worker who serves as Giacometti’s model; his sister-in-law, Odette; and his mother whose funeral he attends before he embarks on his last ride.

His mother’s death awakens memories of boyhood when he learned from his artist/father to draw things as he sees them and to aim for “authenticity rather than perfection.”

For the most part the women characters revolve in Giacometti’s orbit and don’t have their own autonomous lives. The wives, lovers and models for Picasso and Rodin were often their co-creators. Was that true of Caroline and Annette one wonders? Giacometti’s Last Ride leaves that question unanswered, though the novel offers hints. One would also have liked one or two overtly political figures and perhaps a cameo appearance by Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Schneider dedicates the novel to “Catherine, who drove with me along the winding Giacometti road.” He says that she “opened her French kitchen to him.” Not surprisingly, mouth-watering food and wine are almost as decisive in these pages as art. Giacometti is always ready for champagne and oysters, though his stomach gives him acute pain and sends him to a hospital.

The narrative, which is told effectively through concise dialogue, moves deftly across the landscape of Paris. It slows down long enough to situate the artist in his atelier, where he clashes and conspires with his models.

“I don’t plan to die now,” Giacometti tells Caroline. “I have too

much work to do. And then there’s the problem of loving you.” She responds, “Problem?” He asks, “who’s going to love you if I’m not around?”

A loveable figure in large part because he’s not narcissistic, Schneider’s Giacometti is an artist worth knowing and admiring as a human being with charms galore. Chester Arnold’s sketches bring bits and pieces of bohemian Paris to life: a pack of Gauloises, the trademark French cigarette; Giacometti’s atelier with its detritus and unfinished pieces; café society; and the artist’s “last ride” in a lovable, funky Citroen 2 CV, known as a “deux chevaux.” (Because it only had “two horsepower.”)

In these pages, the ubiquitous car becomes an icon for Giacometti himself and serves as an emblem for Paris before it was displaced by New York as the cosmopolitan capital of the commercial art world. There’s a lot more than two-horse power in the creative engine that drives this well-crafted novel that paints a picture of what the French call “la condition humaine.”

The post A Country for Old Men appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed