Sam Bankman-Fried nervously sheds his dark brown prison jumpsuit to reveal athletic shorts and a loose-fitting gray T-shirt.

“There’s this extremely dumb cat and mouse game where, for reasons no one has ever bothered to articulate, between the hours of like 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. on weekdays, the only clothing we’re allowed to wear is the one-piece prison jumpsuit,” he explains, settling into a plastic chair in a cinder-block room. “So I’m just gonna keep an ear out. And if I hear noise, I’ll sort of scramble to put the jumper back on.”

Bankman-Fried, universally known as SBF, still seems to feel some kind of imperative to skirt rules he deems illogical or contradictory. Depending on who you ask, that might be what landed him in prison, serving 25 years for orchestrating one of the biggest financial crimes in history. “You know, I never defrauded anyone,” he says. It’s a sentiment he expresses again and again, despite the findings of a jury: FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange he founded in 2019, was never bankrupt. The billions he was found guilty of stealing, never gone.

It’s February 2025, and our reporters are on a call with SBF, one of more than a half-dozen interviews we conducted with him over the past year. How we ended up face to face with the fallen crypto mogul was happenstance. A chance introduction to Joe Bankman and Barbara Fried, the esteemed Stanford legal scholars who are Bankman-Fried’s parents, eventually yielded a meeting with SBF. Bankman (who advised FTX) and Fried are now part of his legal team and are preparing to appeal his conviction. They, like their son, want to rebut the public narrative of the wayward “Crypto King” who scammed investors out of $8 billion.

SBF was not yet 30 when he became one of the world’s youngest billionaires. He was the cherubic face of a flourishing alternative financial system poised to upend the world economy. Crypto was surging. Celebrities from Lionel Messi to Kim Kardashian to Mike Tyson were signing on to promote various digital currencies. “Drive your Lambos to the moon!” Lindsay Lohan exhorted the crypto faithful in a paid spot in 2021, predicting the price of bitcoin would top $100,000. FTX was helping to provide the rocket fuel for the industry’s stratospheric ascent.

FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried arrives at the federal court in New York in February 2023. He was later sentenced to 25 years for orchestrating one of the biggest financial crimes in history.Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty

With his trademark wild, bushy hair, SBF appeared on the covers of Forbes and Fortune, which likened him to the “next Warren Buffett.” FTX, meanwhile, was everywhere. The company ran a Super Bowl ad starring Larry David. It bought the naming rights to the Miami Heat’s arena and the field at UC Berkeley’s California Memorial Stadium. An apostle of a techie philosophy known as effective altruism, which among its wealthiest followers essentially boils down to making the most money to do the most good, SBF was heralded as a new breed of tech baron—more ethical, more philanthropic—and he was making waves in both political and charitable circles.

“They shouldn’t trust us. They should look at the facts.”

And then, over the span of nine days in the fall of 2022, his empire came crashing down. An industry news outlet called Coindesk got ahold of a balance sheet belonging to SBF’s private trading firm, Alameda Research. It showed that Alameda’s books were stuffed with an FTX-created token called FTT, suggesting that the trading firm, which SBF had portrayed as a totally separate and independent entity, “rests on a foundation largely made up of a coin that a sister company invented.” The story was the first in a series of dominoes to fall, eventually leading to the revelation that Alameda had borrowed heavily from FTX to cover speculative investments. Panicked investors raced to withdraw billions from the exchange and many found they could no longer access their holdings. Soon, the Bahamian police were leading SBF out of his luxury apartment complex overlooking the Caribbean.

The verdict, finding him guilty of seven counts of fraud and money laundering, placed him alongside Bernie Madoff and Elizabeth Holmes in the rogues’ gallery of infamous swindlers. It’s a saga Barbara Fried describes as “a Bonfire of the Vanities,” name-checking Tom Wolfe’s famous novel about a young Wall Street bond trader who is railroaded by a cabal of politicians, journalists, and assorted scoundrels.

“When I get really angry,” she says with tears in her eyes, “sometimes it’s at the thought of Sam in prison, sitting there with everything he could do for the world, destroyed.”

&Subscribe to Mother Jones podcasts on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast app.

In their bid to vacate his conviction, SBF and his parents argue that the saga’s real villain is one of the world’s most powerful law firms, Sullivan & Cromwell. They allege that the firm wrestled FTX away from him, installed a new CEO named John J. Ray III in his place, and profited handsomely from the company’s downfall. The firm would ultimately play a critical role in getting SBF locked up, while going on to pull in nearly a quarter-billion dollars in legal fees.

John Ray has said SBF was living a “life of delusion”; that, from the wreckage of Bankman-Fried’s crypto house of cards, he and Sullivan & Cromwell salvaged billions to repay FTX customers; and that SBF’s criminal trial and the ongoing bankruptcy proceedings shred his claims about FTX’s solvency and about his own culpability.

So when it comes to questions of SBF’s guilt or innocence, why should anyone trust his parents?

“They shouldn’t trust us,” Fried says. “They should look at the facts. And many of the relevant facts are public, they’ve been public for a long time. All we would say to people is, ‘You have heard one side of the story only.’”

Barbara Fried and Joe Bankman, parents of FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried, outside federal court in New York City in March 2024. In their bid to vacate his conviction, SBF and his parents argue that the saga’s real villain is one of the world’s most powerful law firms, Sullivan & Cromwell.David Dee Delgado/Getty

The collapse of FTX may be the last thing many people heard about SBF and the financial colossus he created and destroyed. But the story didn’t end there. It has played out in bankruptcy hearings and in a maze of lawsuits; at industry conferences; on social media sites where creditors gather to swap info and strategize; and in the federal prison where SBF huddles daily with his legal team on video calls to plot his appeal.

We spent the past year investigating FTX and the aftermath of its collapse, an untold tale featuring as many twists and intrigues as Bankman-Fried’s path to the top of the crypto industry. Along with SBF and his parents, we interviewed company insiders who had a front row seat to FTX’s implosion, bankruptcy experts and former federal prosecutors, crypto investors battling to get their assets back, and opportunists seeking to profit off the carnage. We reviewed thousands of pages of court transcripts, legal filings, and internal corporate documents. We even read SBF’s unpublished 300-page prison memoir, dubbed Manfred, after the stuffed dog that accompanied him from his childhood home on the campus of Stanford University to Cambridge (where he attended MIT) to his Bahamian redoubt.

Our investigation doesn’t exonerate SBF. It does raise questions about Sullivan & Cromwell’s role in the case; about a bankruptcy that has ballooned into one of the most expensive in US history, in which lawyers earned hundreds of millions of dollars while people who lost their life savings waited for recompense; and about a regulatory system that remains little better equipped to oversee the booming cryptocurrency industry than it was in November 2022 when SBF’s $32 billion empire began to crumble.

SBF reached out to possible investors to stop the financial bleeding.He believed FTX was still solvent.He just needed time.

SBF reached out to possible investors to stop the financial bleeding.He believed FTX was still solvent.He just needed time.

Sam Bankman-Fried was among the executives who testified during a House Agriculture Committee hearing in May of 2022.Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Zuma

“It’ll Be a Bad PR Week”

“Can you say how big the hole is?” an Alameda Research staffer asked.

It was November 9, 2022, and Caroline Ellison, Alameda’s CEO and SBF’s on-and-off girlfriend, had summoned employees to an all-hands meeting to address the rumors about the firm’s insolvency that were flying across social media and the company’s internal Slack chats. Slouched in a bean bag chair, she explained that “starting last year, Alameda was kind of borrowing a bunch of money” and plowing those funds into “illiquid investments”—in this case, digital assets and financial stakes in other crypto firms that could not easily be converted to cash. “We ended up borrowing a bunch of funds on FTX,” she said, “which led to FTX having a shortfall in user funds.”

Ellison tried to sidestep the employees’ question about the size of the shortfall, but he pressed. “Is it closer to like one bil or a six bil?” That is, $1 or $6 billion. “The latter,” Ellison replied, laughing nervously.

She didn’t know she was being recorded when she admitted that she, along with SBF and a couple other top executives, were among those in the know. Months later, this call would serve as evidence in SBF’s criminal proceedings, in which Ellison and other executives testified against him. (She is currently serving a two-year prison sentence for her role in the FTX meltdown.)

SBF was slow to recognize the unfolding disaster. He thought little of the November 2 Coindesk scoop revealing Alameda’s balance sheet. “I basically thought, ‘Oh, this is going to be a negative PR thing. It’ll be a bad PR week,’” he recalls. Sam even spoke at a Forbes conference the next day. The article never came up.

A few days later, on November 6, Changpeng Zhao, known as CZ, the Chinese-Canadian crypto mogul who owned FTX’s biggest competitor, Binance, tweeted that he was liquidating his firm’s holdings in FTT, the FTX-created token, “due to recent revelations that have come to light.” CZ’s tweet jumpstarted a multibillion-dollar withdrawal spree, lurching FTX into an existential liquidity crisis.

FTX began playing a game of financial whack-a-mole as it moved money around the exchange to meet the mounting number of withdrawals. SBF reached out to possible investors to stop the financial bleeding. He believed FTX was still solvent. He just needed time.

“At that point, we’re pretty frantically searching for multibillion-dollar liquidity offers that would allow us to just keep filling withdrawals without needing to liquidate potentially $8 billion,” SBF recalls.

Meanwhile, the company quickly retained Sullivan & Cromwell to help it navigate the maelstrom. FTX already had a close relationship with the high-powered law firm, which had represented FTX and its executives on at least 20 occasions dating back to 2021, earning more than $8.5 million in fees. Some of its attorneys had even joined the in-house legal staff of FTX, including Ryne Miller, the general counsel of FTX.US, the crypto outfit’s US subsidiary. Miller had been a staff attorney for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission before joining Sullivan & Cromwell to advise clients on regulatory issues. Now his phone was ringing constantly with government contacts. “Regulators…began calling and the phone number they had was mine,” he recalled in a podcast interview. “And so I heard from pretty much every regulator you can imagine over the course of two or three days wondering what’s going on.”

Caroline Ellison, former CEO of Alameda Research, and SBF’s on-and-off girlfriend, leaves Manhattan Federal Court in October 2023. She is currently serving a two-year prison sentence for her role in the FTX meltdown.Michael M. Santiago/Getty

While SBF scoured for capital to save his company, Sullivan & Cromwell was engaged in a different set of rapidly escalating discussions with Miller and another FTX lawyer about the company’s future that centered on filing for bankruptcy.

At 9:32 p.m. on November 9, Sullivan & Cromwell attorney Andrew Dietderich emailed SBF a plan that would keep him as an FTX director, while appointing a chief restructuring officer to be “on stand-by as the manager of the company in a possible chapter 11.” Sullivan & Cromwell recommended one candidate for the gig: John J. Ray III, a turnaround specialist whose experience in corporate restructuring included presiding over the Enron bankruptcy. Ray was “S&C’s guy,” Miller told a colleague, according to court records. (Miller declined to comment for this story.)

“I don’t want to be the one clinging on to power, when it’s clear to the rest of the world that that shouldn’t be what they’re doing.”

SBF’s legal advisors grew more persistent in urging him to sign off on Ray’s appointment as potential buyout deals collapsed, as freaked-out employees fled the FTX headquarters in Nassau, and as various foreign regulators circled, risking a complex and potentially expensive international fight over the company’s assets.

“There’s extremely large pressure on me to give the company to Sullivan and Cromwell—coming from the law firm itself, from ex-Sullivan and Cromwell lawyers who are working for FTX, from other advisers,” SBF remembers. “It was quite intimidating.”

On November 10, the Bahamian financial regulator took control of FTX’s local operations. SBF came under increasing strain to sign over the company.

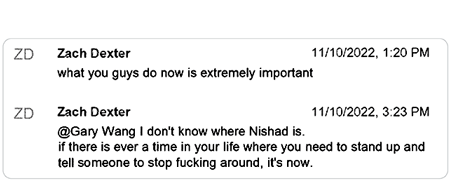

“You have good people around you [who] can help you do the right thing,” Zach Dexter, the head of FTX.US, messaged SBF. “I promise you…doing this now will result in a far better outcome than doing something else.”

Dexter was also firing off more pointed messages to SBF’s inner circle.

“What you guys do now is extremely important,” he wrote. “If there is ever a time in your life where you need to stand up and tell someone to stop fucking around, it’s now.” (Dexter also declined to comment.)

SBF and his legal team were not sold on John Ray. They wanted to do more due diligence on him and explore other candidates. Just after midnight on the 11th, SBF’s personal lawyer reached out to Dietderich, the Sullivan & Cromwell attorney, asking that Ray’s name be stripped from the one page document that had been prepared for Bankman-Fried to sign over control of FTX. Ray’s position, by now, had evolved from chief restructuring officer to CEO, supplanting SBF entirely. (The change in title, Dietderich would later say, came as he and his colleagues started to grasp the “depth of the problem.”)

Signal chat messages from Zach Dexter, shared as part of an exhibit in SBF’s criminal trial.

Dietderich responded incredulously. “We don’t have time. That does not work.” He added, “John Ray is objective, experienced and fair. He is not proposed by anyone with an ax to grind.”

As SBF considered his options, his mind replayed the iconic scene in The Wolf of Wall Street when besieged titan Jordan Belfort, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, is about to sign a deal with the federal government barring him from working on Wall Street. In a farewell speech, he suddenly changes his mind, saying, “I’m not leaving. I’m not fucking leaving!” The office erupts into pandemonium.

“I was thinking, ‘I don’t want to be that,’” SBF remembers. “I don’t want to be the one clinging on to power, when it’s clear to the rest of the world that that shouldn’t be what they’re doing.”

At 4:24 a.m., as a two-day tropical storm cleared out of the Bahamas, SBF signed the document. Minutes later, after receiving a call raising hope of an outside investment in FTX that could save the firm, SBF says he tried to revoke his signature. But it was too late.

For SBF, that morning formed the pivotal moment in his downfall, the moment when he lost control of his company, his story, and eventually his freedom.

“ The single biggest mistake I made by far,” he tells us, “was handing the company over.”

John J. Ray III, CEO of FTX Group, testifies during the House Financial Services Committee at the US Capitol in December 2022. “Never in my career have I seen such an utter failure of corporate controls at every level of an organization,” he told the committee, describing FTX before he took control.Nathan Howard/Getty

“Every CEO in America Is Jealous of This Job”

John Ray had never heard of SBF. His knowledge of crypto? “Absolutely zero.” But he did have deep experience dealing with corporate debacles—Fruit of the Loom, Nortel, Residential Capital—and he quickly pegged SBF as a familiar type of scoundrel.

Parachuting into corporate fiascos wasn’t for everyone, but Ray enjoyed his reputation as a pitbull. “When I get into a problem,” he told one interviewer, “I sink my teeth into it, and I don’t let it outta my sight until it’s resolved to my satisfaction. Very tenacious, very aggressive.”

“Every CEO in America is jealous of this job,” he said. “There’s a business that’s not making money? I go in and I just shoot it. Boom, gone, done.”

After Ray took command of FTX, he immediately filed for bankruptcy and hired Sullivan & Cromwell to oversee the process. He also moved quickly to shut Bankman-Fried out completely, ignoring SBF’s emails asking to speak with him. “It’s pretty clear for me what happened in the company and what his role was,” Ray later recalled, “and I didn’t really want to have any dialogue with him based on what I knew at the time.”

In the first bankruptcy declaration Ray filed, he said the state he found the company in was “unprecedented.” He would later describe the situation he inherited as a “metaphorical dumpster fire.”

It wasn’t just Sam who Ray kept at arm’s length. Other FTX employees, including Dan Chapsky, FTX’s data scientist, say they offered to help him navigate the company’s records to no avail. “They had no idea what they were doing,” Chapsky says.

Caroline Papadopoulos, a certified public accountant and the controller of FTX.US, was no Sam loyalist, but she too was surprised by Ray’s early comments about the company’s record-keeping and compliance practices.

“He had no ability to understand what was going on because he had truly just taken over,” says Papadopoulos, who continued to work for the company during the bankruptcy, until stepping down in April.

The fate of FTX no longer in his hands, SBF was now fighting for his own future. With prosecutors circling and blame landing squarely on his shoulders, he tapped lawyers from the white-shoe firm of Paul Weiss to defend him from potential charges. Against their advice, he launched an PR offensive to put forward his side of the story, sounding by turns naive and insolent.

“Fuck regulators,” he said in a lengthy text message exchange with a Vox reporter. Semafor reported the next day that Paul Weiss had dropped him as a client.

By early December 2022, Congress was demanding answers. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), then chair of the House Financial Services Committee, invited Ray and Bankman-Fried to testify. The night before the hearing, SBF was polishing his testimony when he received a call from his lawyers informing him that the Bahamian police were on their way to arrest him. He raced to complete his remarks, arguing with his mother over edits, in hopes of sending it on before he was perp-walked out of the building. (The testimony he planned to deliver began, “I fucked up.” The rest centered on defending himself.)

“A bad dream,” Barbara Fried remembers of that day.

Sam Bankman-Fried is led away in handcuffs by officers of the Royal Bahamas Police Force in Nassau, Bahamas, in December 2022.Mario Duncanson/AFP/Getty

In DC, the hearing went forward without SBF. In her opening statement, Waters noted, “The timing of his arrest denies the public the opportunity to get the answers they deserve.” Ray, the only witness at the hearing, took the opportunity, after four weeks of collecting and reviewing FTX’s data and documents, to reemphasize his stark assessment of FTX’s condition.

“Never in my career have I seen such an utter failure of corporate controls at every level of an organization,” he said. Though some members of Congress viewed FTX as a cautionary tale about the economy-jeopardizing dangers of crypto, Ray saw things differently: It was just another case of “old-fashioned” embezzlement, and not very sophisticated fraud at that.

A wary Biden administration had earlier that year ordered government agencies to study the risks and benefits of the burgeoning digital asset industry as a first step toward developing national policies, but as FTX became a case study in the perils of unregulated crypto, it launched an aggressive crackdown. Soon, the Justice Department targeted Binance, whose CEO, CZ, had helped to push FTX past the brink by offloading his company’s FTT holdings; he would later serve four months in jail for violating anti-money laundering laws. SEC investigations into crypto exchanges like Coinbase, Gemini, and Kraken followed. Industry proponents complained that the Biden White House was engaging in “regulation by enforcement”—neglecting to impose clear rules while clobbering the industry with fines and lawsuits. By April 2023, Chamath Palihapitiya, the venture capitalist and co-host of the All-In podcast, was declaring that the crypto boom was over, at least as far as the US was concerned. “Crypto,” he said, “is dead in America.”

Ricardo Santos; Nathan Howard/Getty

No Ordinary Law Firm

The month after the congressional hearing, a bipartisan foursome of senators, including Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), wrote to the judge overseeing the FTX bankruptcy, questioning Ray’s hiring of Sullivan & Cromwell, given its extensive history with FTX. “The law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell advised FTX for years leading up to its collapse,” they wrote. “This same firm, Sullivan & Cromwell, is conducting the investigation into the apparent fraud and criminal activity.” Their letter added that “somewhat shockingly, Sullivan & Cromwell claims it is ‘disinterested.’”

Sullivan & Cromwell is no ordinary law firm. It got its start advising the robber barons of the Gilded Age, including John Pierpont Morgan, on railroad and industrial mergers, helping to forge the US Steel monopoly and to finance the Panama Canal. It has remained at the heart of American corporate and political power ever since. Past members of the firm include the Dulles brothers, Allen and John Foster, who served as CIA director and secretary of state respectively. Tech mogul Peter Thiel spent a brief stint as a Cromwell associate. Its role in geopolitical affairs has been controversial—it did business in Nazi Germany and represented the American subsidiary of chemical maker IG Farben. In the 1950s, the firm worked on behalf of the United Fruit Company, as it pushed for a US-backed coup d’état in Guatemala.

“When you think of old line, powerful law firms, the platonic form is Sullivan and Cromwell,” says Temple University’s Jonathan Lipson, a bankruptcy law expert who has tracked the FTX case closely. Nearly every source we spoke to about Sullivan & Cromwell invariably mentioned its size and power. Some refused to discuss it, even off the record. Sullivan & Cromwell’s mighty reputation is captured in the title of a book about the firm, A Law Unto Itself, which describes its “combination of secrecy and important clients” as “unmatched.”

“FTX wasn’t supposed to be part of the risk. The risk was the investments you choose to invest in, not the platform you choose to invest in.”

Sullivan & Cromwell’s representation of FTX raised eyebrows since the firm might have to investigate itself as part of the bankruptcy. “Never heard of it. Never heard of it,” Lipson says of this unusual arrangement. “In Enron, for example, the two main law firms before bankruptcy—they obviously weren’t going to be counseled to the company in its bankruptcy, and instead, you’d have independent lawyers and independent investigators coming in and figuring out what went wrong.”

Lipson ultimately filed a court brief supporting the appointment of a special examiner to investigate whether Sullivan & Cromwell had violated its ethical duties. In it, he questioned whether Sullivan & Cromwell had violated its ethical duties since it appeared to promise SBF a role reorganizing his company “while simultaneously seeking to induce his prosecution.”

A couple days prior to the bankruptcy filing, Sullivan & Cromwell attorneys, after consulting with FTX.US general counsel Ryne Miller, had reported accounting concerns to the US Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the law firm stated in a court filing. SBF claims these discussions, which began to lay the groundwork for the charges against him, occurred without his knowledge. Ray’s team would later say that Sullivan & Cromwell’s pre-bankruptcy outreach was of “critical importance to the speed with which federal prosecutors have been able to charge and arrest Mr. Bankman-Fried.”

Once Ray took over, Sullivan & Cromwell’s cooperation with prosecutors deepened. It sent over balance sheets, organizational charts, employee contact information, customer contracts, and more—a treasure trove for the cases the Justice Department and SEC were building against SBF, who later fired back in a court filing, alleging that Ray and Sullivan & Cromwell had been “deputized…as federal agents to review and synthesize the evidence for them.” It was a strategy that SBF and his supporters considered outrageous: Instead of repaying creditors, his company appeared to be paying Sullivan & Cromwell to help put him in prison.

“Sullivan & Cromwell…silver plattered it a little bit with the prosecutor’s office,” says Paul Pelletier, formerly the chief of the Justice Department’s criminal fraud division.

“Everything around lawyer duties says you really shouldn’t do that without at least informing the highest person at the company,” Lipson argues about Sullivan & Cromwell’s alleged coordination with prosecutors. “And that would have been Bankman-Fried.”

Lipson eventually got his wish. An independent examiner was appointed, over Sullivan & Cromwell’s objections, but the mandate was limited. Instead of carrying out his own investigation, former US Attorney Robert Cleary was tasked with “compiling and summarizing the completed and ongoing investigations,” including those conducted by Sullivan & Cromwell and the outside counsel it had hired to probe its potential conflicts. Cleary largely didn’t conduct interviews or review primary documents, he noted in his first report, which determined that Sullivan & Cromwell’s past work for FTX did not disqualify the law firm from representing the company through the Chapter 11 process. Cleary said he had seen no records “in which S&C expressly disclosed a crime” prior to the bankruptcy filing and also saw no evidence that the firm had knowledge of fraud or misconduct by FTX.

A Sullivan & Cromwell spokesperson says the examiner “investigated and thoroughly debunked these false narratives.” The FTX Estate—the entity, led by John Ray, managing the bankruptcy—said:

“The FTX Estate managed its chapter 11 case in a transparent, public process that was supervised by the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, reviewed by an independent examiner and had the full support of the official creditors committee. Its Plan of Reorganization received the approval of more than 95% of creditors who submitted votes, representing 99% of voted claims by value. We are proud of the integrity and impact of the work we have done with our large team of committed professionals, which has recovered billions of dollars in assets and enabled the return of 100% of bankruptcy claim amounts plus interest for non-governmental creditors to support the victims of Sam Bankman-Fried’s criminal conduct and fraud.”

Lipson is still struck by the firm’s attempt to thwart an independent investigation and says questions remain unanswered. “It was, I think, quite surprising that S&C resisted as aggressively as they did given the kind of Chapter 11 case this was,” he says, “a freefall preceded by allegations of serious misconduct.”

“We were treated like digital peasants.”“Our money, our lives, our rights, everything has been taken by a system that protected itself and the powerful people managing it.”

“We were treated like digital peasants.”“Our money, our lives, our rights, everything has been taken by a system that protected itself and the powerful people managing it.”

Sam Bankman-Fried outside Manhattan Federal Court in June 2023.Michael M. Santiago/Getty

Bankruptcy Bonanza

Sunil Kavuri was a longtime investment adviser who had worked for Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley, and J.P. Morgan. When he began dabbling in crypto, he was skeptical. “The industry was rife with numerous frauds, hacks and scams,” he wrote in a victim impact statement to the court ahead of SBF’s March 2024 sentencing.

But FTX seemed different. “It was backed by among the largest venture capitalists in the world,” Kavuri recalled. SBF also met routinely with regulators in Washington, DC, had hired one of the nation’s leading law firms, Sullivan & Cromwell, and “utilised international celebrity endorsements to create an impression of a credible, trusted, and legitimate exchange.”

When FTX collapsed, Kavuri had some $2 million in crypto in his account—investments earmarked, in part, for his young children’s education. “I was bereft and unable to function,” he wrote. “I couldn’t eat or sleep for days.”

In the weeks that followed, Kavuri launched a class-action suit against celebrities who had served as paid spokespeople for FTX, including Tom Brady, Shaquille O’Neal, and Shohei Ohtani in an effort to hold “fraud enablers accountable” and compensate victims. (The case is ongoing, though many of the claims were dismissed in May. O’Neal, for his part, settled for $1.8 million.) And he became a self-appointed champion for FTX victims, helping to build an online community of creditors who tracked every development in the proceedings.

“The FTX bankruptcy estate is proposing to scam FTX customers again.”

“Sam’s victims are my friends and have become like my family,” Kavuri said in his statement. “They come from all walks of life, but they all shared a belief that investing in cryptocurrency through FTX proved an opportunity to accomplish their financial goals.”

The majority of FTX customers, like Kavuri, lived outside the US, where the bankruptcy was unfolding. Before its collapse, FTX had only recently started operating in the US through FTX.US. Financial regulators here had been slow to devise rules governing the new frontier of digital currencies, and often adopted an adversarial stance toward crypto firms. It was the reason he established his operation overseas. But now it meant that the vast majority of FTX’s creditors were foreigners for whom the labyrinthine US bankruptcy process felt impenetrable.

One of the victims who found her way into Kavuri’s orbit was Lidia Favario. She had spent a year struggling to find answers about what had happened to her assets and how she could get them back. An Italian citizen living in London, where she made a modest living modeling for art classes, she had lost her savings, the remnants of a legal settlement from a car crash that had resulted in 20 operations on her face in her late teens.

She, like many other FTX users, was blindsided by the collapse. “I was first confused and disappointed, and then quite suicidal,” she says.

FTX users were well aware of the hazards of trading volatile cryptocurrencies, which could jump or decline by double-digit percentages in the space of a day.

But “FTX wasn’t supposed to be part of the risk,” explains Tareq Morad, a Canadian creditor. “The risk was the investments you choose to invest in, not the platform you choose to invest in.”

It wasn’t just creditors who were tracking the bankruptcy closely. An entire industry exists to purchase and trade the bankruptcy claims of creditors and cannibalize the assets of fallen corporations. “They literally are vultures,” says Thomas Braziel, “and I guess I’m one.” Braziel is a claims buyer who specializes in crypto assets. People in his line of work offer upfront payment to sellers desperate to cut their losses while betting they will eventually be able to recoup more through the bankruptcy process. “It became a bonanza,” Braziel says. “ It’s up there with Lehman, Madoff, and Enron as like huge cases where there were billions of dollars of trade claims.”

Kavuri, working to fend the vultures off, was imploring creditors to hang tight and assuring them that John Ray, the FTX bankruptcy’s frontman, would recover most of their money.

“Our overarching objective is to maximize value for FTX customers and creditors, so that we can mitigate to the greatest extent possible the harm suffered by so many,” Ray told Congress in December 2022.

A few months later, Braziel bumped into him at an industry event. Braziel pointed out FTX still contained valuable assets, especially its venture portfolio, which included large stakes in startups such as Robinhood and AI firm Anthropic. “Nah, Thomas, all this stuff’s dog shit. It’s dog shit,” Ray replied, according to Braziel. In a milder version of the same point, Ray had told Congress that the venture portfolio “may be worth a fraction of the cost.”

“Mr. Braziel’s representation of the conversation and situation are patently false,” the FTX Estate said in a statement. “Mr. Ray has indeed expressed the view that, although some of the assets that FTX bought with customer property may result in value to the Estate, certain investments in the overall venture book…were most likely bad investments. With the passage of time, this has proven to be accurate.” The independent examiner found that many of these investments were made with “limited due diligence…and were often based on unsupported valuations.”

Weeks before this encounter, Ray and Sullivan & Cromwell sold off an FTX-owned firm called LedgerX to a group of investors that included Zach Dexter, the FTX.US chief who had urged SBF to step aside from his company. Dexter had run LedgerX, a small exchange that specialized in crypto futures and derivatives, prior to its 2021 acquisition by FTX for nearly $300 million. SBF considered LedgerX particularly valuable because it was authorized by regulators, finally giving FTX a foothold in the US market. Now, Dexter and other investors bought the company back at the slashed price of $50 million. Sullivan & Cromwell’s Andrew Dietderich argued in a bankruptcy court appearance that LedgerX had been a “horrible investment.” It seemed an awkward admission from a partner of a law firm that had helped FTX broker the initial deal, billing $1.5 million for its work.

Lipson, the bankruptcy expert, noted the quick sale also didn’t add up, since Ray himself had said weeks earlier he lacked reliable financial information. “If so,” wrote Lipson and his co-author David Skeel in a journal article about the bankruptcy, “it is unclear how Ray and S&C—much less potential bidders—could have known the value of the entities with confidence.”

“The sale price was the result of a public auction in which LedgerX was sold to the highest bidder,” the FTX estate said in a statement. “The Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors and the Bankruptcy Court approved the sale without objection.”

The LedgerX deal also raised early internal red flags about FTX’s ties to Alameda Research. LedgerX staffers raised concerns about FTX code that effectively gave Alameda special “backdoor” privileges—essentially unlimited borrowing from FTX—and LedgerX’s chief risk officer, Julie Schoening was fired when she raised the issue, according to the Wall Street Journal. (Schoening, who the paper reported signed a nondisclosure agreement, did not respond to interview requests. SBF and another FTX insider contend that it was well known within the company that Alameda had the ability to borrow from FTX and vice versa.)

Sullivan & Cromwell continued to advise FTX after the acquisition as it fielded inquiries from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, including about the company’s ties to Alameda. FTX eventually told the regulator that Alameda had no “special or unique access to the exchange.” The statement, which Sullivan & Cromwell says it had no knowledge of, was determined to be false by the examiner.

“These people, they were playing around with our lives, with our money.”

Ultimately, the independent examiner said an outside law firm hired by Sullivan & Cromwell to investigate its work related to LedgerX found “no evidence to suggest that S&C attorneys knew that any…submissions to regulators contained false or misleading statements.”

[Content truncated due to length…]

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed