In a country where transgender women are now required to identify as “very high-risk men”, four transgender women dressed as beauty queens and surrounded by giant bouquets of flowers throw candy to the thousands of participants of this year’s Pride march in San Salvador.

Feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements have become the face of resistance in El Salvador, where President Nayib Bukele — known as the “millennial president” and an unconditional ally of Donald Trump — has significantly weakened dissent through increased state surveillance, the persecution of critical voices, and laws that benefit emerging elites.

During his six-year presidency, Bukele has taken control of Congress and the Supreme Court and declared a state of emergency that is now entering its fourth year and resulted in tens of thousands of arbitrary arrests and hundreds of deaths. He has ordered the shelving of laws that had been negotiated over years and he has abolished autonomous institutions and created others under his direct control. He was unconstitutionally reelected last year (El Salvador didn’t allow consecutive presidential terms then), and last month his administration passed indefinite presidential reelection, extended terms to six years, and ended runoff elections.

At the same time, he has also doggedly pursued his goal to erase what he calls “gender ideology”, a catchall, right-wing term that includes everything from sexual diversity, women’s rights, and health programs, to the content of school curriculums.

Erasing institutions

One of the first casualties of the Bukele government’s conservative offensive was the Salvadoran Institute for the Development of Women (ISDEMU), a public institution responsible for directing and coordinating all gender policies. The workers there were among some of the first victims of his government.

On the day in 2022 she finally agreed to sign her resignation and leave the ISDEMU, María — anonymous for fear of reprisals — had endured nearly three years of workplace harassment, marginalization, salary reductions, and mistreatment. She was in charge of a “gender unit” — an entity created in public institutions as a result of the Law of Equality, Equity, and the Eradication of Discrimination against Women (LIE), passed in 2011. She tells Truthdig that she began working there just before Bukele was first sworn in. The change, she says, was almost immediate.

On June 3, 2019, two days after Bukele’s inauguration, María and her team were moved to a smaller, more isolated office. In one of their first work meetings with the new administration, they were informed that they would no longer handle LGBTQIA+ issues. Soon after, she was stripped of her authority to attend inter-institutional meetings with other government entities and told she must receive prior authorization before doing anything related to her unit’s responsibilities.

“I started sending messages: ‘Look, this is scheduled for this month; look, this activity is coming up; look, we want to do this, I would like to be involved; look, I have this process underway.’ They wouldn’t answer me,” María says.

On that same day in June 2019, the Bukele administration also eliminated the Secretariat for Social Inclusion, which was responsible for issues of gender and sexual diversity.

Commemorations of key dates for the gender units, such as International Women’s Day (March 8), Pride (June 28), and the Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (November 25), were quickly sidelined. The Presidential House, María says, messaged the heads of gender units, instructing them to do nothing for those days: no social media posts, no events, no public communication at all.

The budget of the ISDEMU, which also creates gender policies and laws, has been reduced to a husk. In just two years, the ISDEMU lost nearly half of its funding, dropping from USD 12 million annually in 2023 to USD 7 million in 2025. In December 2024, ISDEMU laid off more than 100 employees.

Keyla Cáceres of the Feminist Assembly, a coordinating body for feminist organizations, believes these restrictions on pro-women public policies have had a nationwide impact, particularly at the municipal level. Cáceres says there are now fewer opportunities to report rights violations, and women’s participation in the public sphere has been severely reduced.

During the pandemic, Maria says she went months without receiving a single instruction or directive from her workplace. “I would get ready and be prepared every day to work remotely, but they never got in touch,” she recounts. When she returned after the months of quarantine, her office was moved, and in 2021, she was asked repeatedly to resign from her full-time role. She held on for a few weeks, requesting a transfer and refusing to resign, before finally accepting and being demoted from her position and having her salary reduced. She stayed on for a few more months but had to leave after a high blood pressure crisis sent her to the hospital.

“I had depression throughout 2022,” she says. “I would stay at home in my pajamas, asleep. I mean, I didn’t get back up and take action, and start wanting to do things for myself until 2023. Even now, I’m afraid to imagine myself in a formal work environment again.”

ISDEMU’s annual Report on Acts of Violence Against Women, written with input from all gender units and various other institutions, was last published in 2022, the same year María resigned from her job. Concerned about the sidelining of the issue, feminist organizations have taken it upon themselves to maintain their own records of gender-based violence cases.

Women imprisoned

Since Bukele declared the state of emergency in the country, there have been more than 85,000 arrests, many of them arbitrary, and 447 deaths of people in state custody. International bodies have accused the government of systematic human rights violations. An underappreciated consequence has been the impact on women who have been imprisoned or have had their lives overturned as loved ones are locked up, typically without trial.

Jacqueline, who also requested anonymity for fear of reprisal, has dealt with both. She arrives for an interview with Truthdig with a bag full of documents that are evidence of her time in prison, and of her son’s. Both were arrested on September 21, 2021.

She shares her detained son’s name and photo, and as she speaks about her son, her voice trembles with emotion and her hands shake. She wipes her eyes and shrinks slightly in her chair. She insists her son is innocent and never had any ties to any gang. Neither did she. She says she chose to plead guilty in an expedited judicial process in order to be released in January 2022, two months before the state of emergency came into effect. Threatened with a sentence of up to 10 years in prison, she knew she could do more for her son if she were free.

Currently, part of her sentence involves performing community service in state offices, doing various odd jobs. From there, she returns home to work as a seamstress. After many years as a seamstress for large companies, she can no longer find work due to her criminal record. She now sews at home, mostly on commission.

The last four years of Jacqueline’s life are in her bag of documents: the receipts for the money she tries to send her son every month, her old employee ID cards from textile companies, her son’s rejected habeas corpus petition and some documents from her own court case.

Not in her bag are any mementos from the weeks she spent in the Women’s Prison — now closed and converted into a men’s penitentiary. She says that out of the money her family deposited in her prison account each month, she had to pay 3 US dollars to other inmates just to be allowed to stay inside her cell. These inmates, called rusas, women with a final court judgment, would wash the cells or carry water back and forth in exchange for this fee.

“Toilet paper is more important than food in there,” Jacqueline says, noting that prison conditions have worsened significantly for women after the state of emergency came was declared.

Revista Factum reports that the over 12,000 women incarcerated in El Salvador lack dignified conditions to menstruate; some of them receive just one sanitary pad for an entire week.

Family visits were also suspended in 2020 due to the pandemic, but the measure was extended by the state of emergency. Some relatives have gone nearly three years without any news of their detained family members. Jacqueline found out that her son had been transferred to the Center for the Confinement of Terrorism when she arrived at the prison gate to drop off a package of personal supplies for him. CECOT is the massive prison where 252 Venezuelans, accused with little evidence of being members of the Tren de Aragua gang, were sent from the US as part of an agreement between the Bukele and Trump administrations.

Read more: CECOT: Bukele’s mega prison where “the only way out is in a coffin”

Though Jacqueline and her son, Jefferson Hernández, were not arrested under the state of emergency, their case is being handled by a Court Against Organized Crime, which oversees all cases arising from the state of emergency. These courts operate with “faceless” judges, as it was decreed that their identities cannot be disclosed. Further, last month, legislators also passed a two-year extension to the period of provisional detention, which had already been lengthened by a prior reform. This means that individuals detained under the state of emergency could spend up to five years in detention without a hearing or seeing a judge.

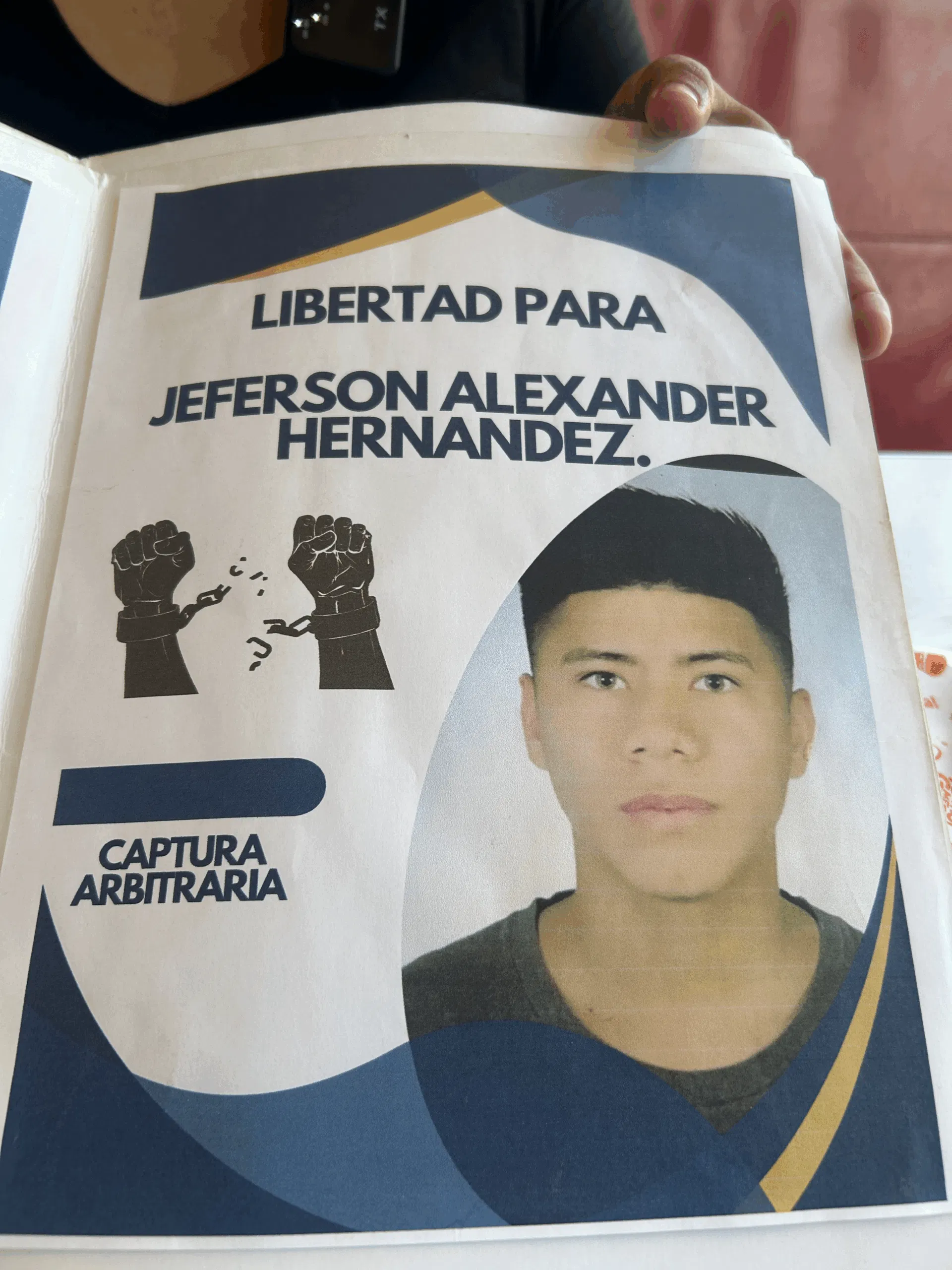

A poster demanding freedom for Jacqueline’s son, Jefferson Hernández. Photo: Suchit Chávez

Among the papers Jacqueline carries in her bag is a banner with her son’s photograph, his name and a plea for his release. It’s the same one she brings to every march, alongside the other relatives — mostly women — who are demanding justice for their loved ones.

She has been participating in the demonstrations by the Movement of Victims of the Regime (MOVIR), a collective that emerged just a few months after the state of emergency was declared. In August, MOVIR submitted a formal petition demanding the Supreme Court declare the ongoing state of emergency unconstitutional.

Silencing diversity

On June 28 of this year, Valentina Vigil marched through the streets of San Salvador in a black dress embroidered with bright flowers, a crown and a sash across her chest that read “Miss Trans Pride — Perlas de Oriente S.M. (San Miguel) Collective.” Vigil is one of the founders of the collective, an organization of trans women from the San Miguel department, east of the Salvadoran capital.

Vigil tells Truthdig that since the collective was founded in 2018, it has done grassroots work and defended the rights of members of the LGBTQIA+ community in coordination with local institutions. But under Bukele, the collective has struggled.

Vigil held a flag with the colors of the transgender pride movement: light blue, pink, and white. The march was large, stretching over 20 city blocks to celebrate diversity in a country where other demonstrations demanding rights — such as the release of those arbitrarily imprisoned or an end to the forced evictions of street vendors — have rarely surpassed 400 people in recent years. This march and the one commemorating International Women’s Day were the largest rallies of 2025, the second year of Bukele’s second term.

Vigil makes a living selling food and clothing. She is immensely proud to be one of the very few — if not the only — trans woman to have been united in a wedding ceremony in El Salvador. It was only symbolic however, because Vigil’s gender identity is not legally recognized in her country.

In 2021, Bukele’s party, Nuevas Ideas, gained a nearly absolute majority in Congress. Among its first actions were not only the illegal dismissal of the attorney general and the magistrates of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice. Bukele and his administration also abandoned years of legislative work, including draft laws that had emerged from dialogue and collaboration with grassroots organizations. Among those was the gender identity law.

Despite the initiative being shelved, the Constitutional Chamber ruled in 2022 that the state must legislate and facilitate name changes for gender reasons. This unprecedented judicial decision enabled members of the trans community to begin the process of legal recognition. This included Vigil, who began the name-change process in 2021 but was not able to complete it.

Following Bukele’s decision to eliminate “gender ideology” from the state apparatus, announced during the Conservative Political Action Conference, the Salvadoran Health Ministry removed all material related to sexual diversity from health institutions and modified forms to eliminate terms like “gay” and “trans”. A trans woman, for example, must now identify as a “high-prevalence male” or a “very high-risk male”. The “prevalence” refers to rates of infection with sexually transmitted diseases.

Vigil says the impact on the LGBTQIA+ population has been rapid and severe. Part of her work involves compiling statistics on violence suffered by the community, providing support for individual cases, assisting users with visits to the HIV and STD clinics, and running awareness workshops.

“The quality of care has declined. Our statistics show that 60% of the LGBTQIA+ population attends the clinics. Before, visitor numbers were higher; but after [the form change] happened, attendance dropped,” she says. Through the collective, she has achieved a small victory: convincing nurses to write the chosen name in parentheses for trans people alongside their birth name. Other individuals, according to the activist, prefer not to use the clinics, despite needing treatment.

Valentina Vigil is a trans woman and a leader of the Perlas de Oriente Collective, which defends the rights of the LGBTQIA+ community. Photo: Suchit Chávez

Perlas de Oriente also suffered losses after Donald Trump canceled US Agency for International Development (USAID) funding. Vigil says one of their projects was ended, and their sensitivity workshops have been put on hold.

Increasing poverty in rural areas

Continuing to work despite having everything stacked against them has become another form of resistance for some women, especially in rural areas. In the canton of El Porvenir, long sleeves and caps or hats are mandatory, even at 6 am the sun will begin to beat down and it will be too hot for workers to continue harvesting the edible flower loroco. Marleny Hernández, head of the Salvatierra Agricultural Production Cooperative Association, leads a group of women and men in the harvest. She has been a farmer since she was 14 and is now over 50.

Everyone moves sideways along the paths between the wooden and wire fences where the loroco plants have twisted and grown. The flower, used as a seasoning in cooking and dairy products, is harvested before its petals have unfolded. Hernández and the others pick the buds and place them in buckets.

“I have seen significant change, going back about four or five years ago. It has been very difficult,” says Hernández. The training she received as a rural woman — leadership, health, self-care and cultivation methods — has stopped now. “There were economic initiatives for us every year, but it’s been several years since they’ve been available,” she adds.

Hernández is a member of the Association of Agricultural Women Producing on the Land, which, she says, had several projects cut following the freezing of USAID funds. “That has affected the association and us a great deal. It’s like a chain reaction,” she says.

Projects like hers are facing further challenges. In early June this year, the Salvadoran Congress passed the Foreign Agents Law, which mandates a 30% tax on any funds received from abroad. The impact has been a reduction in grassroots work and the closure of programs.

Cáceres, the activist with the Feminist Assembly, explains that at least seven organizations have shut down projects because they ran out of funds or out of fear of the Foreign Agents Law, which imposes fines of between USD 100,000 and USD 250,000 for failing to register.

“One of the programs that was shut down, which had a major impact on women’s lives, was for pap smears,” says Cáceres. “This organization was dedicated to working on issues of food sovereignty and sexual health. It didn’t even talk about sexual and reproductive rights. It didn’t touch on comprehensive sexuality education. It was specifically about preventing uterine cancer.” Hernández adds that the nearest health clinic is in another canton, but the care they receive is poor.

In April 2024, the Salvadoran government stopped delivering agricultural packages with seeds, fertilizers and other supplies and instead began distributing 75 US dollar cards that could be redeemed at designated agricultural supply stores. The measure has already led to a decrease in crop cultivation.

Further, Hernández says she signed an agreement in 2024 for support for rural women, which would grant them seedlings, seeds and fertilizers, “but that has been stalled.” She was initially contacted by the gender unit of the Ministry of Agriculture to assemble a group of women beneficiaries, but a year later, they have received nothing.

Exile: a consequence of defending human rights

“I believe that in El Salvador we are experiencing a severe setback in the defense of women’s rights,” says Ivania Cruz, a Salvadoran lawyer now living in exile. She is one of the first high-profile defenders to be forced to flee the country this year. “This is due to the lack of social programs and their closure, as well as the complete cut in funding for projects that were precisely for that: for learning about our rights, for upholding them, for promoting them, for activating mechanisms. All of that collapsed with the arrival of Bukele.”

Cruz has been one of the most visible faces of the Unit for the Defense of Human and Community Rights of El Salvador (UNIDHEC), an organization that in recent years has taken on multiple cases of arbitrary arrests during the state of emergency, as well as the forced displacements of communities due to land claims or urban development projects.

Exile is another outcome of Bukele’s authoritarian drift. An undetermined number of human rights defenders have been forced to leave the country. Cruz was very active in denouncing rights violations related to land tenure, including the arbitrary eviction of dozens of coastal vendors whose businesses were burned down at night by members of the La Paz Centro municipality.

As a result, Cruz has an arrest warrant out against her, but she continues denouncing the persecution of rights defenders from abroad. Women, once victims of the gangs, “are now victims of the state,” she argues. Whether in El Salvador, or in exile, “silence isn’t an option,” she says.

This article was first published on Truthdig.

The post Beating back Bukele’s war on “gender ideology” appeared first on Peoples Dispatch.

From Peoples Dispatch via this RSS feed