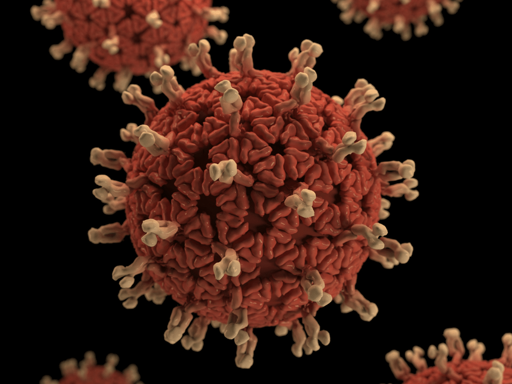

A new report from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has sounded the alarm: the world’s most treasured ecosystems are being weakened by a threat that rarely makes the news. It’s not a drought or a wildfire, but something smaller, quieter, and spreading fast. As the planet heats up, forests shrink, and invasive species move in, a surge of new pathogens is taking hold. These diseases are changing the way nature works, reshaping entire landscapes and pushing vulnerable species closer to the edge.

The IUCN World Heritage Outlook 4 assessed a total of 271 sites, 231 natural, and 40 mixed world heritage sites spread across 115 countries. These sites covered an area of 470 million hectares. And, it reveals a sharp increase in the number of natural world heritage sites reporting serious disease outbreaks.

Scale of diseases

Five years ago, only two sites considered pathogens a major concern. Today, 23 describe them as high or very high threats.

It’s a tenfold jump that signals how viruses, bacteria, and fungi are emerging as powerful agents of ecological disruption, often spreading faster than conservationists can track or contain them.

In the report, Dr. Grethel Aguilar, IUCN director general, highlights that protecting world heritage is essential to preserving the planet’s life, culture, and shared identity:

Protecting world heritage is not just about safeguarding iconic places – it is about protecting the very foundations of life, culture, and identity for people everywhere.

These are some of the world’s most outstanding sites, as they are home to extraordinary biodiversity and geodiversity. They sustain communities, inspire generations, and connect us to our shared history.

The silent spread

Across continents, pathogens are killing species faster than most recovery programmes can respond.

In Africa’s Virunga National Park, Ebola continues to infect great apes, erasing decades of conservation progress. In Argentina’s Península Valdés, the avian influenza A/H5N1 strain has devastated seabird and elephant seal colonies, leaving beaches filled with carcasses.

Half a world away, the Tasmanian Wilderness remains under attack from chytrid fungus, a microscopic invader that has driven amphibian species toward extinction.

In the US, Mammoth Cave’s bat populations have been decimated by white-nose syndrome. Even trees, the quiet giants of the biosphere, are not spared, as the Sundarbans mangroves of South Asia are succumbing to a “top dying” disease that undermines both biodiversity and the coastal protection millions of people depend on.

These aren’t isolated cases, as they form part of a global pattern, what the IUCN describes as the “biological fallout” of a warming planet.

Pathogens are travelling further and faster, their reach increased by climate instability, global trade, and tourism. Stable ecosystems are now becoming laboratories of infection, petri dishes.

Climate change

According to the IUCN report, climate change now poses the greatest threat to natural world heritage sites worldwide, with 43% of sites rated as highly threatened, up from 22% in 2020.

The report links the rise in diseases directly to climate change. Shifts in rainfall and temperature are moving species and the microbes that live on them into unfamiliar territory. Mosquitoes climb to higher altitudes, fungal spores drift further on the wind, birds migrate at the wrong time, carrying parasites into unprepared ecosystems.

In the Arctic, warming temperatures could awaken ancient microbes from permafrost. And, in tropical forests, animals pushed by heat or drought come into closer contact with humans, heightening the risk of zoonotic spillovers.

Meanwhile, n North America, diseases now are above wildfires as a leading threat to heritage sites. In South America, avian flu and coral pathogens have reached epidemic levels. In Africa, diseases like Ebola and canine distemper are merging with chronic challenges like poaching and habitat loss, complicating conservation efforts challenging to manage.

The report calls these overlaps “planetary feedback loops”, where environmental change breeds disease, which in turn weakens nature’s resilience to that very change.

Invasive species and pathogens collide

According to the report, there’s a subtle but deadly partnership: invasive species and pathogens often move together. Rats spread parasites, ornamental plants carry fungi, mosquitoes are spread to new places. These hitchhikers exploit the same pathways as trade and tourism.

Invasive species are already ranked as the second-greatest global threat to world heritage sites, after climate change, and the report warns that biological invasions and infectious diseases are converging into a single crisis.

Without strong biosecurity and early detection, local outbreaks can snowball into continental epidemics.

Interdependence

The report calls attention to how disease outbreaks threaten local communities that depend on ecosystem services. Mangrove dieback in the Sundarbans undermines fisheries and coastal protection for millions. Coral diseases linked to warming seas endanger livelihoods in island nations.

The interdependence of species outlined in the “Once Health” concept argues that the health of people, animals, and ecosystems is inseparable.

Tourism, while economically vital, is also a vector for disease transmission. It highlights that tourism-related activities can cause the spread of invasive alien species and pathogens, especially in island ecosystems.

Science and surveillance to tackle fast-spreading diseases

The IUCN admits that disease monitoring remains incomplete, and assessments rely on patchy information. The report calls for standardised health monitoring across all heritage areas: sampling water and soil for pathogens, recording wildlife mortality, sharing genomic data internationally. It suggests weather forecasting could predict outbreaks months ahead.

In the end, the IUCN’s warning is not about any specific microbe but about the conditions that led them to thrive. Habitat loss, global trade, fragmented governance, these are the real culprits or vectors. Pathogens only exploit the cracks we leave open.

The pathogen surge isn’t just a biological problem; it’s humanity’s fragmented relationship with the natural world. Deforestation, trade, and carbon emissions aren’t separate crises, they’re interconnected, making both people and ecosystems more vulnerable to disease.

Dr Aguilar writes:

The decisions being made today by governments, corporate leaders, and consumers will determine whether we can reverse global biodiversity loss – or experience a catastrophic collapse of our biosphere.

Featured image via Unsplash/CDC

From Canary via this RSS feed