Advertisement near Argostoli, capital of Kefalonia. Photo: Mark Vallianatos (MV)

Prologue

I spent about eight days in late September-early October 2025 with my son and his family traveling in Greece. We started with Kefalonia / Kephalonia / Cephalonia, the beautiful island in the Ionian Sea that gave me birth. We rented a gorgeous two-story house near the sea in the village Pesada in the southern coast of Kefalonia. My son, his wife, and my granddaughter used their iPhone for directions, so we had no trouble tracking down cafes, restaurants, grocery stores or travelling to other villages.

The Elysian Fields of Pesada

I was astonished by the beauty of Pesada: its large and tall trees, open green fields, and several large houses / villas. The streets are narrow, wide, twisting. We walked to a restaurant for dinner and, within minutes, the waiter and I, speaking Greek, knew we were from the same village, Valsamata. The food was tasty, delicious. The people next to us enjoyed their food as much as we did. But they were talking to each other in such passionate way that, smiling, I found myself dreaming of my younger years growing up in Kephalonia.

We visited Valsamata where I still have a small piece of land, which my nephew uses for his honeybees.

Honeybee hives in my land in Valsamata, Kefalonia. Photo: Dionysios Kalouris.

The healer Saint Gerasimos

The main attraction of Valsamata is the monastery of Saint Gerasimos. This gentleman-monk, Gerasimos Notaras from Trikala, near Corinth, moved to Kefalonia in the sixteenth century. In 1554, he founded a monastery for women. Twice a year, August 16 and October 20, thousands of people from all over Greece and other countries attend elaborate festivals celebrating the saint, especially his potential “healing” of neurological diseases and madness.

An old plane tree on the way to the St. Gerasimos monastery. Photo: EV

The St. Gerasimos monastery is a complex of a giant church and hotel-like dormitories for visiting guests. The classical Greek architecture and art shine in the buildings and even the floor between buildings. I was so pleased walking all over the campus of this institution that I talked to an elderly nun sitting alone on a chair next to the door of her dormitory. I introduced myself and praised the beautiful ancient Greek art of the monastery. We talked about the declining standards of Greek learning today. I said to her that it would be wonderful if the monastery built / supported a school for the study of ancient Greek culture. The nun agreed and urged me to talk to the bishop in Argostoli.

This time I did not talk to the bishop. I was too busy, though I have my doubts he would agree to enter the culture his religion, Christianity, nearly obliterated in the last 1,600 years or so. The clergy has it made in Greece. The state pays their salaries. Monasteries own property and land. They grow their own food and do as they please. They are a state within a state. They do nothing for the impoverished country that funds their lavish lives. There’s no separation of religion and state in modern Greece.

We tried to drive to the old Valsamata, the pre-1953 earthquake village, but did not work out. Satellite guidance failed.

An old photo of mine of my favorable olive tree in the old, abandoned village. The house behind the tree was for temporary protection of our sheep and goats.

Our next visit took us to Fiskardo. The name Fiskardo is not Greek. The ancient Greek name of the port town of northern Kefalonia was Panormos. Herodotos of the fifth century BCE mentions the name Panormos (Histories 1.157) but not necessarily referring to the port town of Kefalonia. Panormos became Fiskardo some time in the eleventh century when the barbarian

Panormos (Fiskardo). Photo: MV

Normans conquered Kephalonia in 1084. The name Fiskardo honors the chief Norman, Robert Guiscard / Viscardus (in Latin). He was Duke of Apulia and Calabria and founder of the kingdom of Sicily. He died in 1085 in Atheras, a village near Panormos. Probably because of tourism, the Greek Ministry of Culture keeps the barbarian name Fiskardo over the Hellenic name Panormos.

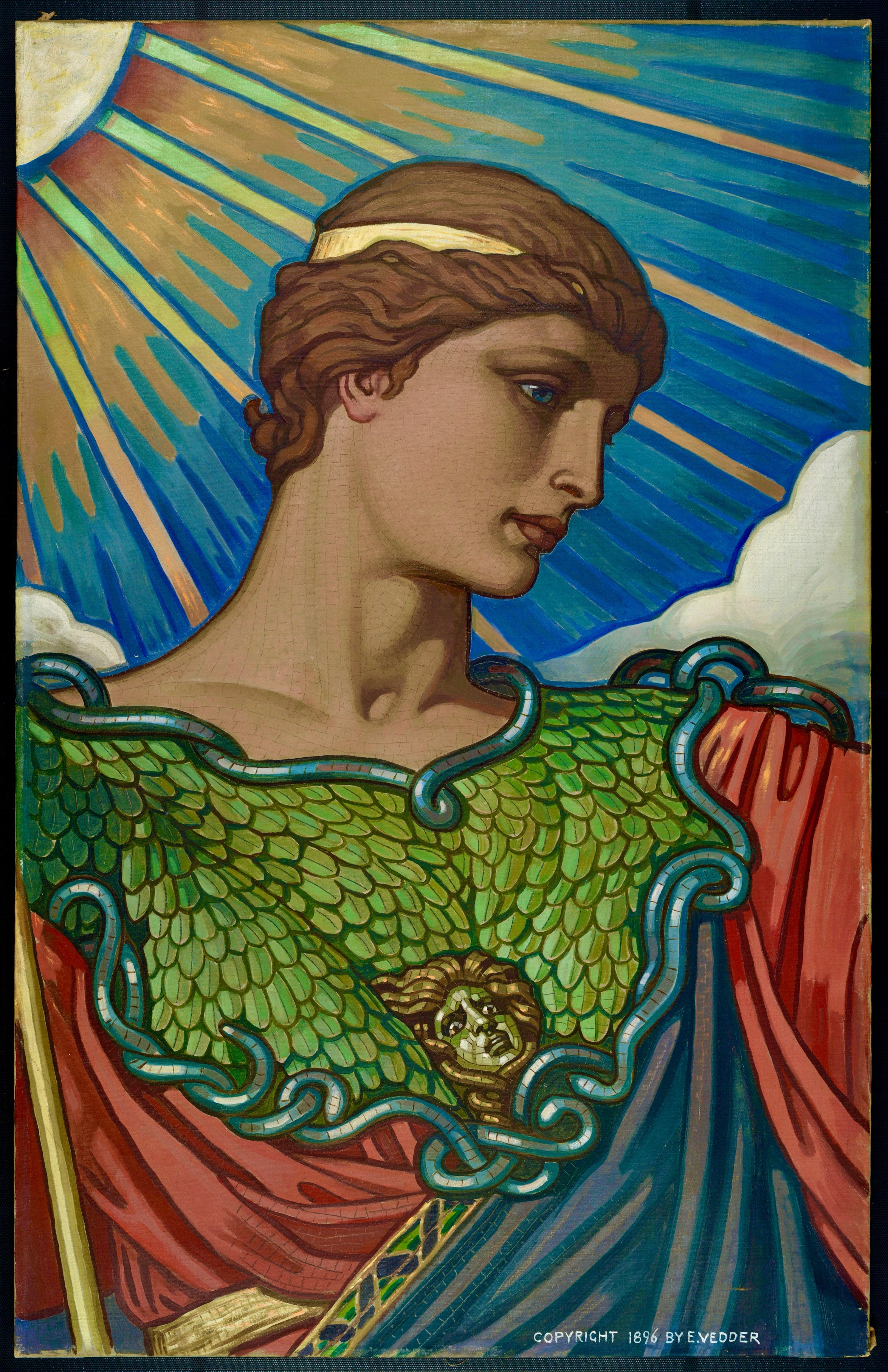

Mosaic depicting Athena / Minerva in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress by the American artist E. Vedder, 1896. Public Domain

In the polis and light of Athena

The second part of our journey started in Athens. We had rented an apartment near the Acropolis museum. The neighborhood is a labyrinth of 6 to 10-story apartment towers, different stores, and eateries — and busy streets. Its hidden beauty comes to light in the evenings and weekends. All the cafes and restaurants fill up to the edge of the streets with people eating, waiters walking and balancing trays filled to the brim with food and drink. Plenty of laughter and talk mix with the smells of the wonderful food. The passerbys look, smell, and dream of joining these open-air symposia.

The smells of these daily affections led us to a couple of farm markets. Entire streets close to traffic and become memorable and practical markets for bread, fish, vegetables, fruits, and all kinds of food. People by the hundreds move slowly, one next to each other, always having their vision towards the two sides of the narrow crowded street displaying food in all its luminous varieties.

Fish and vegetables in a farmers’ market in Athens. Photos: MV

Finaly, we climbed the famous hill of the Acropolis. It was an unforgettable experience. Getting very close and looking intensely at the columns of the Parthenon is the equivalent of time travel to the golden age of Athens after the second defeat of the Persians in the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE.

The Parthenon. Photos: MV

There’s also the universal passion of people visiting the Parthenon. They are putting themselves into the light of Athena, the daughter of Zeus and goddess of intelligence, philosophy, democracy, freedom and defender of Athens. I saw several tourists taking pictures of themselves, smiling, with the temple of Athena, in their pictures. Such affection for Greek culture spills over near the Parthenon, daily, among thousands of people from all over the planet. Such communication and merging of ancient and modern cultures could be, and perhaps is, a great asset of Greece in our troubled times. All these tourists could become ambassadors of the reason-and-beauty-based virtues of Hellenic democracy and civilization.

Conclusion

For this magical transformation to take place, the Ministry of Culture of Greece must do more than regulate, by the hour, the influx of foreigners to the sacred ground of the Acropolis. Greek experts in the history and archaeology of the Acropolis must be there to inform and enlighten the visitors. Offer optional seminars to all visitors. Tell them the brief history of the construction and destruction of the Parthenon. Tell them that the Acropolis was a public works program of Athens, the culmination of a golden age of pride, enthusiasm and confidence after the heroic defeat of the Persian invaders. Tell them that, a millennium later, after the Roman emperor Constantine in the fourth century dumped Hellenic and Roman culture, Christian authorities desecrated the Parthenon by converting it into a Christian church. And when the Mongol Turks captured the Greek state in 1453, Parthenon underwent another desecration by becoming a Moslem mosque. In addition, in the early years of the nineteenth century, Lord Elgin, British ambassador to the Ottoman Turks, cut off the freeze of the Parthenon and carried it to England, where it has been kept in the British Museum to this day.

I think this brief history, done accurately and without exaggeration, would strengthen the visitors’ respect and love for ancient Greek culture. Philhellenism would blossom. It’s also possible that learning and accepting historical truth might bring modern Greeks, who are primarily Christians, closer to the virtues of the good and the beautiful, moderation, science, courage, political independence, democracy, freedom and civilization of their ancient ancestors.

In his play, The Suppliant Women, Euripides has Theseus, an Athenian hero, say to the Theban herald that Athens was a model of enlightenment, compassion and generosity. “The dead must be buried,” he says. “That is a sacred law. Athens has no despot. It is a free polis ruled by no one man. In Athens, people rule in annual succession. They do not yield the power to the rich. Poor are rich Athenians are equal before the law” (400-409).

The post Dreaming of Greece appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed