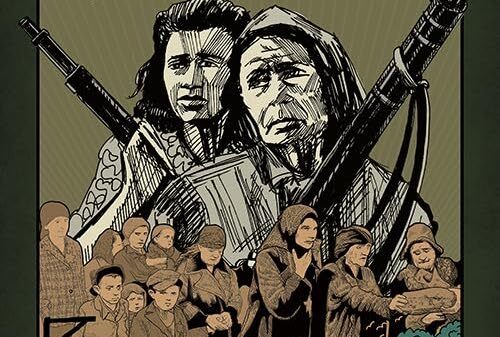

Cover art for the graphic novel Partisans: A Graphic History of Anti-fascist Resistance edited by Paul Buhle and Raymond Tyler

Leonard Cohen sings a song called “The Partisan”. It tells the story of an antifascist fighter in the heart of the war against Nazism. Beautifully rendered by Cohen on his 1969 album Songs From a Room, it tells the story of an antifascist fighter and his squad in what I assume to be the French countryside. By the time the tune is over, the teller of the tale is the only survivor. In the middle verses, the listener is introduced to a woman who gives the three fighters shelter and “Kept us hidden in the garret/Then the soldiers came/She died without a whisper.” The tragedy in this verse, so beautifully told, represents the facts of resisting fascists; fascists whose concern for the lives of those whose opinions they don’t share is virtually non-existent and is perhaps exceeded only by the anonymity of those who bomb and kill from the sky.

Recently, the Trump regime made the modern antifascist movement—known as antifa—a primary target in its establishment of a fascist USA. Although my immediate reaction to the announcement labeling antifa as a domestic terrorist organization involved at least a couple jokes regrading the essential ignorance of the White House declaration, it was underlined by the potentially greater danger that ignorance created for opponents of the trumpist movement. Because there is no actual entity that is antifa, the forces of law and order can label anyone opposed to Trump and his authoritarian program a domestic terrorist. Once an individual or organization is labeled in such a manner, even the pretense of civil rights and liberties pretty much disappears. Likewise, so do people.

Fighting fascism is a serious business. The recent case of writer and scholar Mark Bray is but one example of this. Bray’s primary work opposing fascism was to write a book titled Antifa: The Antifascist Handbook discussing fascism’s modern manifestations and the nature of the opposition to it. Right wing students at Rutgers University where he taught began a campaign of harassment in an ultimately successful campaign to force him out of his job. The harassment included threats to his family and himself; threats that convinced him they should leave the United States. For people who know the history of those opponents of Nazism who left Germany during the early years of the so-called Third Reich, Bray’s exile can’t help but make them wonder who will be next. Or how far will the installation of fascism progress around the world in the current period. When does the opposition to fascism require more than sarcasm, more than protest and how would that opposition look?

Of course, only time will give us the answers to those questions. In the meantime, it seems like a good practice would be to familiarize oneself with the history of resistance to fascism. There are dozens of texts, films and websites that are quite instructive for that pursuit. Some are fictive in nature and others are straight-up history and analysis. One recent addition to this collection of antifascist history is a supremely rendered graphic history titled Partisans: A Graphic History of Anti-Fascist Resistance. Edited by comics writer Raymond Tyler and longtime leftist historian Paul Buhle, this collection of handsomely depicted histories of various elements of the resistance to European fascism during World War Two is an inviting introduction to this under acknowledged aspect of the war against fascism in the twentieth century. The artwork, which ranges from the vivid colors of Seth Tobocman’s portrayal of the Yugoslav partisans under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito to the classical black and white cartoon panels of Daniel Selig’s entry on the French Partisans, invites readers young and old into a history that is simultaneously informative and inspirational. The narratives bend from the first person narrative of David Lasky’s water colored story of a Jewish uprising in eastern Europe to a story about the Soviet Partisans written and drawn by Raymond Tyler that reminded this reviewer of vintage Our Army at War comics from my 1960s childhood.

The different politics of various partisan groups is part of the conversation in several of the dozen stories in this collection. So are the differences based on ethnicity and religious beliefs. Women’s roles in the resistance are mentioned. Indeed, longtime comics writer Trina Robbins’ (the creator of Wimmen’s Comix) collaboration with artist Anne Timmons tells the story of three young Dutch women who served with the partisans in the Netherlands. Another story titled “Piccola Staffetta:My Small Contribution to the Resistance Against Mussolini” composed by Franca Bannerman, Isabella Bannerman, and Luisa Caetti is a tale about a girl who realizes she has been brainwashed by the fascists and joins the resistance performing small but important tasks. While reading this particular chapter, I was reminded of Hans Fallada’s novel about Nazi Germany and the small acts of resistance of a middle-aged couple*, Every Man Dies Alone.*

The moral of these stories and the watchword for any opposition to fascism is simple and evident throughout this graphic history. It’s not any kind of heroism that matters, but the resistance itself.

The post Antifa: A Graphic History of its Origins appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed