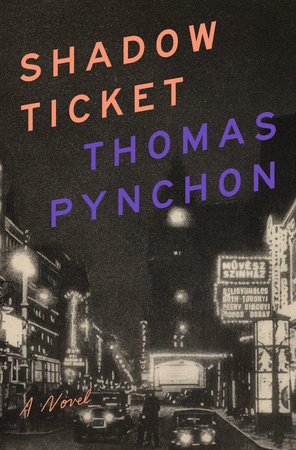

German Bund parade in NYC, 1939. Photo: New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Public domain.

Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket whisks us way back to 1932 amid shantytowns and lindy-hopping in the end times of prohibition as fascist creeps creep into daily life not yet beneath the annihilating nuclear rainbow arc of the V2 missile. There is a possibility of averting the future away from what is yet unwritten, to err away from the nightmare that haunts today’s living.

The nightmare of fascism, the historical burden that was only peeking its shadow out below the storm clouds. On the way back, the characters return to an America they no longer recognize, while lingering in a nostalgia for a time that cannot return, and without giving any plot spoilers away, the ending felt extraordinarily prescient. It even wraps up some long-standing mysteries in his work. Who was the Kenosha Kid? We may have some clues, and other appearances from the Thomas Ruggles Pynchon extended universe make the story fun for long-time fans of his work.

Shadow Ticket is part detective novel; however, the lead character has a Gumshoe Manual that runs out of helpful advice, there is no text to crack the code of the metaphysical mysteries of the cosmos, part Beatnik romp through Europe, part James Bond movie, Romcom replete with cheesy meet cutes, monster pulp fiction, and Pynchon’s inverse lost world tropes.

Although there is head-hopping, we take it in stride. Pynchon fans are smart and can follow the main character Hicks McTaggert’s shadow ticket to Hungary. In all of Pynchon’s novels history mirrors the present, and the present is a funhouse mirror of history. In the way that Trumpian America of 2025 admires, desires contemporary Hungarian authoritarianism.

Hypermodernity forces us into multiverses, pluralities, relativisms, and this open sea of choice for the sake of choice creates a dizzying subjective experience of the world. and

Hicks McTaggert is perhaps named after J.M. E. McTaggart, the philosopher who wrote “The Unreality of Time,” a philosopher of time not named Martin Heidegger? And think of the thematic color scheme of shadows in noir. Black Mask magazine, Heidegger’s Black Notebooks, and his participation in Nazism with its Black Shirt Rallies, smoke-filled rooms, clandestine shakedowns, meetups under misty night bridges, secretive entourages, people who appear and then are not what they seem at first blush. If we are in a multiverse metaphysics not centered on the Heideggerian notion of radical situatedness, grounding, and alleviating angst, then the story is rhizomatic, cut loose of place, time, national boundaries, and so forth.

In this novel, there are U-Boats in Lake Michigan, German immigrants in Milwaukee who are strikebreakers and perhaps sleeper cells of the Third Reich and Italian folks who laugh along with Mussolini, and do not yet have the foresight (or hindsight) of seeing the aftermath of fascism yet sympathize with it in its germinal form.

Consider the lively exchange between Uncle Lefty. Is he “poised to overthrow the U.S. government? Itself? Ja? One word from the Kaiser, no questions asked—straight into action, half a million nationwide.” (pg. 64)

When the characters return to America, it is not the same America.

Are we supposed to villainize the Italian Americans who are tagged with every crime in Milwaukee in the aftermath of Al Capone’s reign of power? Or, are the ‘bad guys’ among the German immigrants who would support Germany if America declared war on Germany, or the familiar trope of running evil candidates that the people can imagine having a beer with (or, in this case in Milwaukee during Prohibition, going to a speakeasy)

“How about your pal Hitler, you’re handing your life over to this li’l comedian now?”

“Hey, just a friendly brat-and-beer get-together—we’re National Socialists, ain’t it? So—we’re socializing. Try it, you might have some fun.” (pg. 66)

As there are basically parties in almost every chapter of the book, it’s important to see that in Pynchon’s hands, the Nazis were not these austere rule enforcers, Puritanical tightwads of American lore.

They know not what they are doing, even though they are doing it that is problematizes the fascist creeps, although fascist creeps are not the central antagonists of the novel, and it is basically impossible to say what the most important plotlines are, because the book consists almost entirely of red herrings, lines of flight, and shifting rhizomatic foundational schisms.

Adrift in what feels like the dying heaves of the American Empire, each day seems as though we are surrounded by a bloody future nobody would have dreamed thirty years ago. Always arriving and departing, every page is pregnant with twists and turns, unpredictable characters appear in ways replicating the contingency of the lived present as it bleeds into the future, with plot completion being the least interesting aspect of the story.

Do we really care if the protagonist detective Hicks McTaggert catches the “bad guys”? I know I didn’t. We are lead to believe that the Milwaukee Police Department are clueless racists blaming Italians for everything, and McTaggert’s cohort of investigators in the Unamalgamated Ops are not these virtuous soldiers of justice, as Hick’s boss aptly named Boynt Crosstown (the urban dictionary tells us “Boynt” means “chode”) is a Pynchonian cast that toes the line of virtue, they provides detective work for mobsters and the rich who live in the wealthy suburb of Shoreline take all the juiciest high paying cases from the rich suburb of Shoreline while they’re stuck in the Third District, and provides a kind of panoptic panoramic detective work spanning the entire region.

Can there be a detective novel comprised entirely of red herrings? Pynchon takes us to a time when things were not known, these characters did not have the luxury of WW2 hindsight (as we in 2025 do not have the hindsight of the next decade, yet?).

This is not the most interesting part of this novel. What’s fascinating is how Pynchon pulled off an allegedly alternative history, tells us a story from such wildly variegated stories and raison scenes that seem to appear in the most topsy turvy way, around each corner, on the next page, there is no way to predict what will happen next, what characters we will meet next, and Pynchon makes it completely believable as he tells this fantastic fictional story.

Shadow Ticket transports the reader to another place too, too familiar to our time to be complete fiction. As any Pynchonian nightmare laces fiction with historical facts full of a motley canvas of creeps, anti-heroes, forgotten actual heroes, only to come out the other side in a different consciousness, not necessarily improved.

Whereas in Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s 1973 masterpiece, we are presented with the problem of eternity personified by the character Benny the Bulb, a light that never goes out, in Shadow Ticket the empire is a candle at the end of its wick, “there’s that last bulb, once so bright, now feebly flickering, about to burn out.” (page 269)

As I finished reading this book a wave of sadness washed over me. Pynchon has made such a massive impact on the world in ways that are unspeakable in ordinary life. He writes with such brutal honesty about truths that are only approachable through comedy. This book is a way of saying goodbye to an old friend as we say goodbye to America as understood through the nostalgia industry. In one scene in the book, characters return to America and explain that they are returning to something quite different than the America they left. It is difficult to explain exactly what happens when reading a Pynchon novel, but the experience of reading the book leaves the reader changed, the book constitutes a transformative event in and of itself, however, this is the process of living in America in the current era.

Shadow Ticket’s cunning passages, contrived corridors, and issues, like America, deceives us with whispering ambitions and guides us by vanity so that by the end we have not reached a safe, grounded, conclusion. In Shadow Ticket we find ourselves in an ongoing process where knowledge can never absolutize, there is never a final return or arrival. Hence, the sleuthing of Hicks McTaggert, our protagonist gumshoe from 1932 Milwaukee, draws us into a widening circle of social possibilities.

First, it is a miracle that this book exists. This author is not beaten into dank submission, and can write subversively, and not just politically, but trope subversions appear on every page.

This book contains rampant facts, and it’s not about verifying true correspondence between mind and thing, rather than obtaining a virtuous, true record of events as they happened, Shadow Ticket ought to be praised for its subversive storytelling, genre-defying structure, and emotional resonance. It’s described as a transformative reading experience—both a farewell to a literary icon and a lament for a fading vision of America.

The post Pynchon’s Farewell to America’s Vanishing Dream appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

From CounterPunch.org via this RSS feed