As Brazil prepares to host COP30 in Belém this November, a new investigation by Repórter Brasil exposes how the country’s booming biofuel industry is driving deforestation, labour abuse, and land conflict, all in the name of sustainability.

Approved in October 2024, Brazil’s biofuels bill highlights the true cost of its clean energy drive. The rapid expansion of ethanol, biodiesel, and so-called sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is reshaping rural Brazil, threatening key ecosystems, and widening inequality.

The report, based on fieldwork, legal records, and supply-chain mapping, paints a more complex picture of an industry Brazil plans to showcase as the cornerstone of its decarbonisation strategy at COP30.

Brazil’s biofuels: A climate leader with a carbon shadow

Since launching the Proálcool programme in 1975, Brazil has positioned itself as a global pioneer in renewable fuels. Today, it produces more than 37 billion litres of ethanol and 9 billion litres of biodiesel a year, and it aims to generate 2.8 billion litres of SAF by 2035.

Brazil’s biofuel and feedstock exports hit record levels in 2024, with 1.88 billion litres of ethanol shipped mainly to the United States and the European Union. The country also exported 98.8 million tonnes of soybeans, mostly to China and Europe, along with 408 tonnes of palm oil to the US and European markets.

Public money has poured into it too. The state development bank, BNDES, and Brazil’s innovation agency, Finep, have channelled R$11.7bn (approximately £1.6bn) into the sector since 2022, largely through the government’s Climate Fund.

These numbers will be at the centre of Brazil’s message in Belém, that home-grown biofuels can help deliver on its Paris Agreement pledge to cut emissions by up to 67% by 2035.

Yet, deforestation remains Brazil’s main source of greenhouse gases. According to the report, “land-use change” (LUC), driven by agricultural expansion for fuel crops, is cancelling out many of the supposed climate gains.

Soy: the Cerrado sacrificed

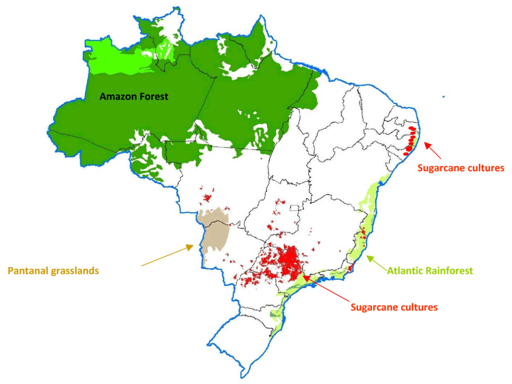

Nowhere is that contradiction clearer than in the Cerrado, a vast tropical savanna known as Brazil’s “water reservoir”. It has become the country’s main frontier for soy, which supplies 70% of Brazil’s biodiesel.

The area planted with soy in the Cerrado region has grown sixteen-fold since 1985, and the biome overtook the Amazon in 2023 as the most deforested region.

The investigation found that even soy from illegally cleared land still finds its way into biodiesel supply chains through a practice known as “soy laundering”.

One supplier linked to multinational trader Bunge cleared nearly 100 hectares of protected vegetation. Others in the Matopiba region (spanning the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia), stripped 11,000 hectares between 2021 and 2023.

Half of Europe’s soy imports now come from Brazil. Yet, under the EU’s new anti-deforestation law (EUDR), much of the Cerrado remains exempt because it’s classified as “non-forest”.

Conservationists warn that this loophole could keep the chainsaws running, even as Brussels tightens the rules.

Beef tallow: the cost of ‘green’ diesel

Beef tallow, another raw material for renewable diesel and SAF, tells a story of hidden emissions and human cost. Framed as a “waste product”, it’s tied to cattle farming, the single largest driver of Amazon deforestation.

Brazil exported 320,000 tonnes of beef tallow last year, up 30% more than the previous year, with 94% going to the US.

The investigation links these exports to serious abuses. Repórter Brasil traced shipments from meatpackers accused of sourcing cattle from rancher Bruno Heller, accused by federal police of being the “largest deforester in the Amazon”, and from farms where inspectors recued workers held in slavery-like conditions.

In 2024, the Saudi oil firm Aramco was among the companies that bought from a supplier later implicated in such a case.

Certification systems fail to catch these risks. Under schemes such as ISCC (International Sustainability & Carbon Certification), traceability starts at the slaughterhouse, not the farm, leaving the origins of “waste” fat unmonitored.

Because the animal phase is excluded from carbon accounting, diesel based on tallow can appear “low carbon”, even when linked to forest loss and forced labour.

Palm oil and violence in Pará, COP30 host

In the state of Pará, where COP30 will take place, the expansion of palm oil has brought violence and violations.

In the towns of Acará and Tomé-Açu, riverside and quilombola (descendents of Afro-Brazilian slaves) communities, and Tembé Indigenous families, report land seizures, blocked river access, and armed security around plantations operated by BBF (Brasil Biofuels), which supplies palm oil for biodiesel and SAF.

Court records examined by Repórter Brasil show 1,697 labour lawsuits against palm oil companies in Pará alone, one of the highest counts in Brazil. Workers complained of lack of drinking water, toilets, and fair pay.

Sugarcane: slavery reborn

Sugarcane, the symbol of Brazil’s ethanol pride, has also being tainted. In 2023, inspectors rescued 32 workers from degrading conditions on a plantation supplying ethanol producer Colombo Agroindústria, a supplier to Raízen, the world’s largest sugar and ethanol company. The workers had no toilets, clean water, and proper bedding.

A separate inspection at a corn-ethanol construction site in Mato Grosso uncovered the country’s largest rescue in years: 563 workers trapped in debt bondage, sleeping in overcrowded, unlit rooms. The project had been financed with R$500m (approximately £69.7m) from the Climate Fund.

“The workers arranged for old, dirty, and torn mattresses to be placed directly on the floor or on makeshift beds to avoid contact with venomous animals in their accommodation,” inspectors reported.

Experts attribute the surge in abuses to the outsourcing of plantation labour, which allows large companies to distance themselves from conditions on the ground while still profiting from cheap labour.

Jorge Ernesto Rodriguez Morales, lecturer and researcher in environmental policy and climate change governance at Stockholm University, spoke about the environmental impact of bioenergy production:

“Current climate policy positions biomass-based fuels as a replacement for fossil fuels in the transport sector, with sugarcane ethanol as a flagship solution for greenhouse gas reduction in international climate negotiations. However, scaling up bioenergy production can have serious socio-environmental impacts.

“Like food production, ethanol requires land, water, and nutrients, meaning that a large-scale expansion could intensify the negative side effects of agricultural growth.”

Indirect emissions

These stories expose the gap between Brazil’s rhetoric and reality. While the government’s Renovabio programme rewards producers of “low carbon” fuels with tradeable credits, it ignores the indirect emissions caused when forests are cleared elsewhere to replace farmland converted to biofuel crops.

Studies show Renovabio ignores the impacts of Land Use Change (LUC) through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for calculating greenhouse gas emissions from biofuel.

Safeguards

Brazil’s biofuels bill offers an ambitious plan, one that could decide whether Brazil’s renewable fuel revolution survives its own contradictions. It calls for crop expansion to be limited to land that is already cleared or degraded, and for full traceability of every plantation and processing plant through geolocation mapping.

To address the issues with supply chain, the report urges the government to extend cattle sector tracking systems to bovine tallow, linking each batch of fat used for biodiesel to the individual animals it came from through records and invoices, allowing auditors to follow the trail from slaughterhouse to refinery.

Suppliers would face mandatory screening for ties to deforestation, forced labour, or illegal land repossession with public disclosure of results.

Experts agree the reforms are overdue, but they warn they will fail if costs fall solely on small farmers.

For researchers and campaigners, the demand for transparency must ultimately come from the markets that buy Brazil’s fuels. Without that pressure from Europe, the US, and global investors, the country’s energy transition risks remaining a promise on paper, while its forests and workers continue to pay the hidden price.

The moment of truth in Belém

Nearly 50 years after Proálcool began, Brazil’s biofuel dream stands at a crossroads. It has delivered technical innovation and jobs, but it has also deepened old inequalities (exploitation of workers known as bóias-frias ) and accelerated deforestation in some of the country’s most fragile biomes.

Morales spoke about the Brazilian government’s position and priorities concerning the expansion of biofuel production:

“In foreign environmental policy, the Brazilian government has historically been reluctant to prioritise environmental protection over economic growth, often attributing major environmental issues to developed countries.”

As COP30 approaches, the government plans to promote the Belém Commitment for Sustainable Fuels, pledging to quadruple global production by 2035. But without stronger safeguards, Brazil risks turning its climate initiative into an environmental liability.

As delegates gather in Belém, Brazil’s green promises are on trial: will biofuel politics crush them, or is the climate summit just witnessing another round of empty rhetoric?

Featured image via Wikimedia commons

From Canary via this RSS feed