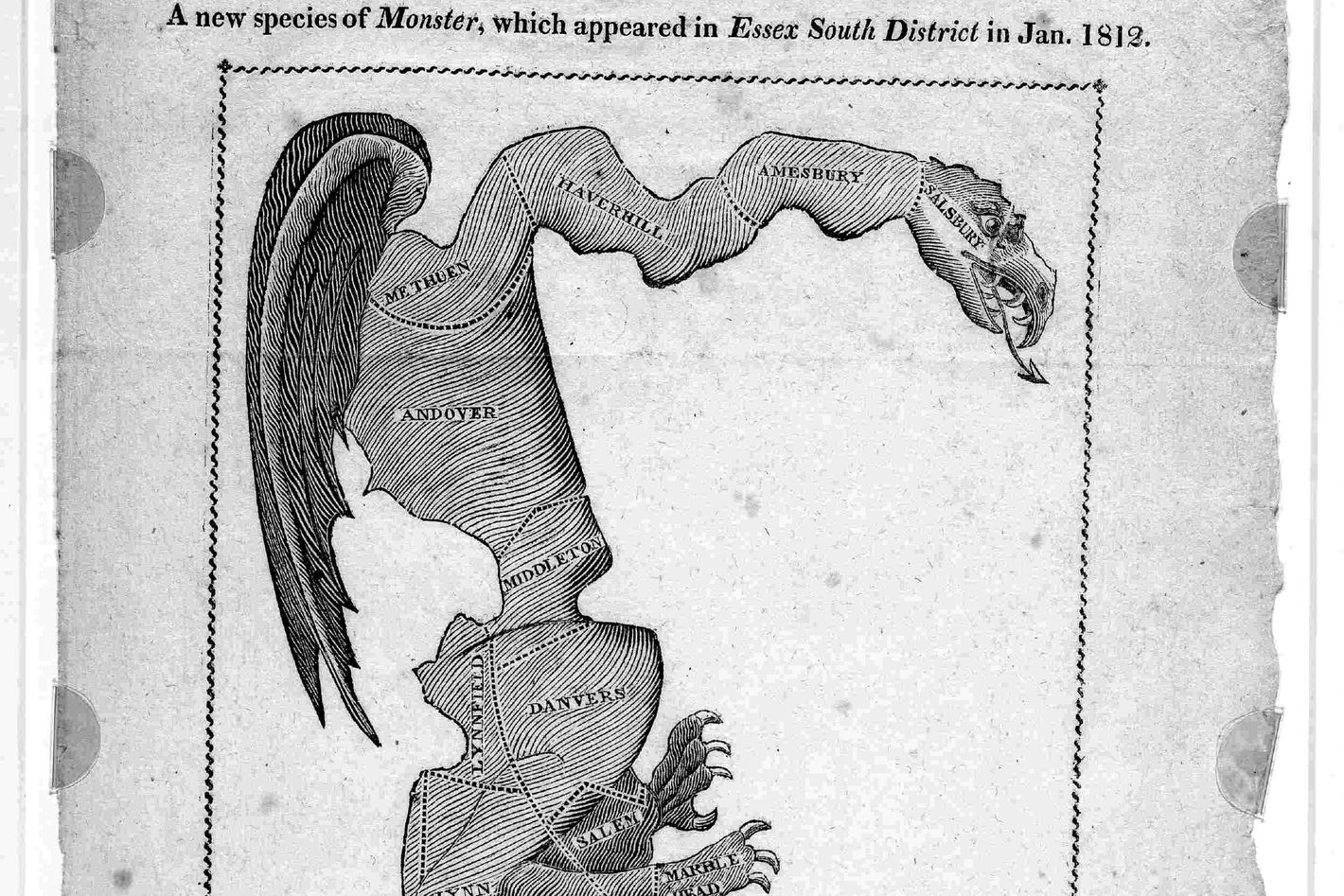

Illustration: Library of Congress

The mid-decade congressional gerrymandering that Donald Trump kicked off by instructing Texas Republicans to grab five additional districts before the 2026 midterms was startling to anyone with an understanding of how these things normally work. Traditionally (at least in the 20th century), redistricting happened every ten years following the decennial census and the reapportionment of U.S. House districts between the states. This expectation created considerable stability in congressional delegations with changes mostly attributable to shifts in the political weather, demographic trends that slowly changed the complexion of districts, and the occasional scandal or primary upset.

Yes, there were a few mid-decade power grabs in recent years (notably another GOP coup in Texas engineered by the infamous Tom DeLay in 2003) and a few other unscheduled remaps compelled by court decisions. But there’s been nothing like the sudden chain reaction that has led to some scheming wherever one party controls the redistricting process. The gerrymandering craze spread from Texas to the Republican states of Missouri, North Carolina, Indiana, Kansas, and Florida and, in response, to the Democratic states of California, Illinois, New York, Maryland, and Virginia.

But if you go back to the 19th century, this sort of thing wasn’t rare at all, as Joshua Zeitz explains at Politico:

Throughout the Gilded Age, state legislatures treated redistricting as a political cudgel … With little judicial oversight and volatile shifts in partisan control, state politicians wielded mapmaking as an extension of electoral combat. Whenever one party captured the governorship and legislature, it redrew district lines to tilt the playing field and expand its share of congressional seats — sometimes mid-decade, sometimes repeatedly within a few election cycles …

Nowhere was that more apparent than in Ohio, where lawmakers redrew the state’s congressional map an astonishing seven times between 1878 and 1892 as Democrats and Republicans traded control of the legislature and governorship … One Democratic redraw, urged on by House Speaker Samuel Randall in 1878, flipped nine seats and preserved his party’s tenuous majority in Congress. A decade later, also in the middle of a 10-year census cycle, Republicans returned the favor in Pennsylvania, carving out 21 safe GOP districts out of 28 and seizing back control of the U.S. House — and with it, unified command of the federal government.

Other states followed similar patterns. In Alabama, Democrats redrew the map in the mid-1870s, packing nearly every Black Belt county into a single district to quarantine Republican votes. In Missouri, Democrats undertook a mid-decade 1878 redistricting alongside Ohio’s, flipping seats that helped preserve their narrow House majority. And in Maine, Republicans’ 1884 gerrymander proved so effective that it delivered them all four congressional seats for the next five elections, even though they won only about 54 percent of the statewide vote.

In some respects, the chaotic landscape was even worse than it is today. Prior to the landmark Wesberry v. Sanders “one person one vote” decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964, legislatures could and did pack voters into congressional districts of unequal population. Eventually the reform movements of the 20th century killed off mid-decade gerrymandering and then another important restraint was put into place by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned redistricting decisions at any level of government that diluted the power of minority citizens to choose or influence their representation. This indirectly placed a limit on partisan gerrymandering, at least to the extent that minority voters tended to become concentrated in one party.

But the conservative Supreme Court majorities of the 21st century have eroded these limits. In 2013, the Court issued a 5-4 decision that essentially gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which for over three decades had required advance Justice Department approval of redistricting decisions in jurisdictions with a history of discrimination against minority voting rights. Then in 2019, another 5-4 majority ruled that the federal courts had no business regulating partisan gerrymandering. That meant that what was left of the VRA represented the only federal restraint on power grabs via redistricting.

And now, just as Trump is inaugurating a new era of gerrymandering, the Supreme Court is considering a case that might wipe out restraints on racial gerrymandering altogether as an obsolete practice no longer needed in a color-blind society (or perhaps one, as the Trump administration argues, in which the only discrimination is against white people). And that could lead to Gilded Age levels of remapping, particularly by Republicans motivated to wipe out majority- or plurality-Black districts in the South. As Nate Cohn and Jonah Smith explain, all bets would be off:

For decades, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which has been interpreted to require the creation of majority-minority districts, has effectively put a ceiling on partisan gerrymandering, especially in the big diverse states. It hasn’t merely been a limit on gerrymandering; it’s the only meaningful federal limitation on partisan gerrymandering.

So if the Supreme Court strikes down Section 2, as it is considering, any equally populated House district is fair game, at least as far as federal law is concerned. There would be no federal law that might deter a 38-0 Texas congressional map that unanimously elected Republicans, or a 52-0 map in California with nothing but Democrats.

You might think the principle of mutually assured destruction would keep either party from going in this direction, but as we are seeing this year, Republicans have a built-in advantage in any gerrymandering arms race, because (a) they have trifecta control of more state governments by a 23-to-15 margin, and (b) Democratic-controlled states are more likely to have their own constitutional limitations on gerrymandering (such as the one California voters are being asked to set aside on November 4). And once the ball is rolling, neither party has much reason to exercise self-restraint.

So in this as in so many other respects, Trump is opening a Pandora’s box with his gerrymandering crusade, and no one knows in the long term who will win or lose — other than voters unlucky enough to live in a state where they are in the minority.

More on Politics

6 Things to Know Now That It’s Election DayWaiting, Impatiently, for 2028Cuomo Racks Up Weird Endorsements From Trump and Musk

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed